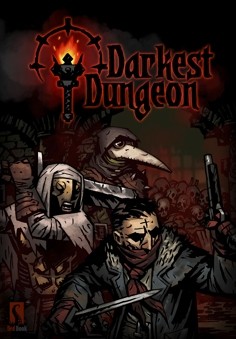

Game review: Darkest Dungeon, where terror and madness await

In this morbid and demanding role-playing adventure, only the least stressed will survive, so stay calm and keep fighting

Red Hook Studios

“Slowly, gently,” intones the noble bass of Darkest Dungeon’s narrator as a foe bleeds out and slumps to the ground. “This is how a life is taken.”

Except it is sometimes anything but. During one quest I stumbled across an altar and, despite specific warnings, offered flame and summoned some Eldritch terror from the void. My party was terrified by the sight – then, as the first member was cut down, they were driven mad.

I hammered the retreat button as another hero fell, and the final two escaped alive. Back in the waking world, brains spinning at what had just occurred, one had a heart attack and died on the spot. The last survivor looked at the corpse, clutched their own chest and fell. Everyone dead, quest over, all loot and treasure gone, all investment in those heroes lost. Sacrificed on the altar of curiosity, for a cosmic kick in the teeth. Darkest Dungeon (Linux/Mac/PC/PS4/PS Vita) is a turn-based battler with an overarching structure, and one idea that lifts it way above the ordinary. This is stress, the idea that people subjected to the kind of horrors that dungeon explorers go through might crack under the pressure. Each hero has their own stress meter, which is regularly added to by everything from it being too dark to the presence of a killer god, and when a tipping point is reached their mental fortitude is tested. In some cases they’ll respond favourably and inspire their compatriots but, far more often, the mind breaks.