Tibetan Buddhist nuns take up feminism and seek equal status with monks

Change is in the air at world’s biggest Tibetan Buddhist academy, in China’s Sichuan province, as nuns stand up for themselves and for Tibetan women as a whole. Monks appear split on their demands

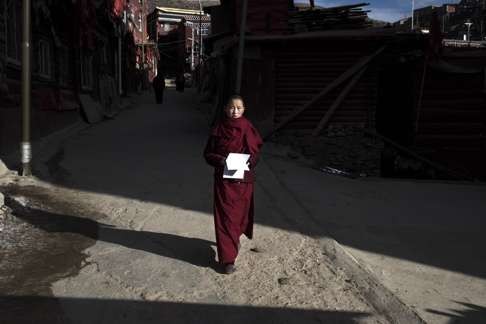

Religiously devoted and with a shaved head and flowing burgundy robes, Xinde Shijiamouni has all the trappings of a Tibetan Buddhist monk. But her serenity is troubled because, as a nun, she cannot reach the same clerical status as a man.

In the harsh terrain and relative isolation of western China, Tibetan culture has long been patriarchal. Now more than 100 nuns at the Larung Gar Buddhist Institute – the largest Tibetan Buddhist academy in the world – are challenging that, holding study sessions on feminism and sparking a nascent religious movement.

If you look at Buddhist law, you can see both genders should be equal

The group have published a series of books on female Buddhist figures and put out a magazine once a year. But many senior monks view their calls with suspicion, decrying sexual equality as a “Western concept”.

“If you look at Buddhist law, you can see both genders should be equal,” said Xinde Shijiamouni – whose name is a pseudonym meaning “The Heart of the Buddha” – “but many on the outside don’t understand the dharma, and many on the inside choose to ignore it.”

More than 10,000 men and women study at the institute, living in red wooden huts, crammed into a steep valley at 4,000 metres altitude in an ethnically Tibetan part of Sichuan province, that surround the main buildings.

Neither Tibetan Buddhism nor the institute allow women to achieve the same religious status as men, denying them the highest rank of ordination, bhikkhuni, which is held by tens of thousands of monks.

“We should be able to do as well as monks,” a senior nun declared at a graduation ceremony at the Larung Gar nunnery last year.

One activist nun, who declined to give her name for fear of reprisals, said: “We’re doing this because we nuns have been under attack for so long. We need to teach women to stand up for themselves.”

But China’s government takes a dim view of religious and political movements not directly under its control – including women’s rights campaigners. An annual meeting of feminist nuns from across Tibetan areas has to be held in secret because it lacks official approval.

READ MORE: Higher learning

Beijing is deeply opposed to Tibetan nationalism and has been seeking to reduce the number of students at Larung Gar for over a decade. About 2,000 of the distinctive red student huts were demolished in 2001.

Most of the novices are female, but according to researchers the stark sexual inequality in Tibetan society contributes to many nuns’ choice to take the cloth.

“Aside from the religious aspect of working for karma and having a better reincarnation, another reason women become nuns that is not very openly talked about is that life as a Tibetan laywoman is hard,” she said.

Women do most of the work in rural and pastoral families, who make up more than 90 per cent of Tibetans, she added.

As well as their theoretical discussions, the Larung Gar nuns have an outreach programme for laywomen in surrounding areas on female health issues. “All religions teach compassion and helping others. We’re helping women to improve their health,” said one nun. “That’s not a controversial issue.”

“Change will be slow, it may be a decade or more,” she said. “But these nuns can eventually change Buddhist society and possibly even Tibetan society as a whole.”

Women can hold bhikkhuni status in some countries that follow Buddhism’s Mahayana and Theravada traditions, including China, Korea, Vietnam and Sri Lanka.

We’re helping women to improve their health. That’s not a controversial issue

The Dalai Lama has backed research to address sexual inequality, but women are denied it in his Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, although the exiled Nobel laureate once told a US awards ceremony that he considered himself a “feminist”.

“Isn’t that what you call someone who fights for women’s rights?” he asked.

Older monks at Larung Gar are sceptical of such notions.

“The ideas of ‘gender equality’ and ‘feminism’ are entirely foreign,” said Wangchuk, a 45-year-old monk walking on the sun-soaked plaza outside the main monastery hall. “Tibetan Buddhism has generations of history and tradition, we don’t need outsiders interfering with that.”

But younger lamas are more open.

“It’s good for the nuns to study gender equality. The world right now is too unequal,” said Pema, 23. “We need more people working to make life fairer.”

Agence France-Presse

.png?itok=arIb17P0)