2016 Venice Architecture Biennale shines spotlight on users of buildings

Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, director of this year’s global showcase, forgoes the flashy steel and glass for structures of brick, wood and rammed earth and a theme of fighting inequality

The 48-year-old Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena calls his dense, earnest and grass-roots edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale “Reporting From the Front”. The show, which runs until November, collects work from a range of architects operating on the forward lines of what Aravena calls “battles” against inequality, crushing poverty and environmental crisis and puts it on display with the informality of a journalistic sketch.

They borrow money; running through this biennale is a multifaceted critique of global real-estate speculation and its effects on domestic life.

They borrow ideas from other architects, from pools of collective knowledge or from the past. And they borrow the kinds of spaces common to the sharing economy: the back seat for the Uber ride, the bedroom for the Airbnb stay.

The emphasis is very much, as biennale president Paolo Baratta points out, on the “demand” (as opposed to supply) side of the architectural equation. This biennale shines a spotlight not just on the architects who design buildings but the people who use, buy, rent, build and clean them.

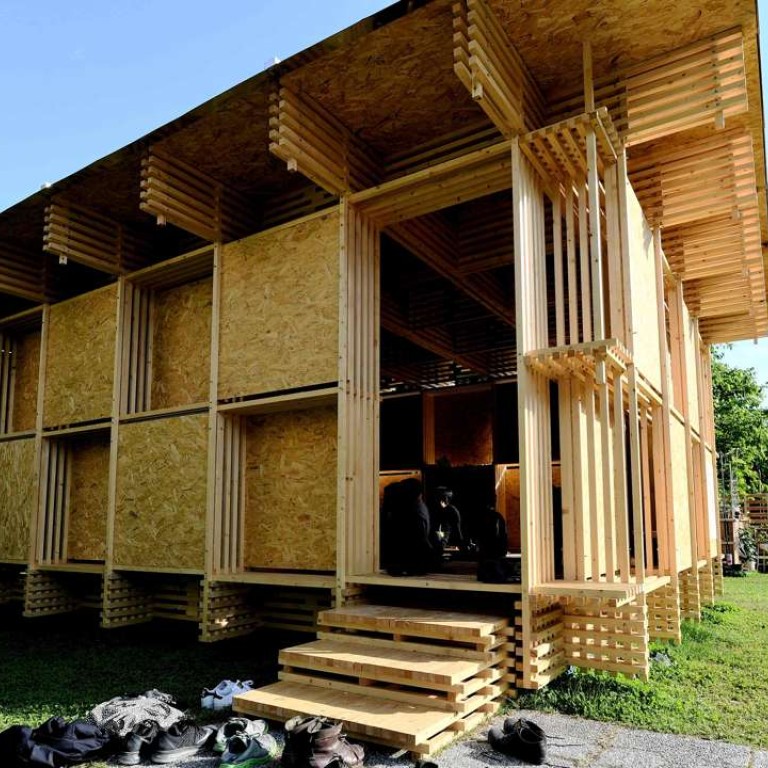

In material and visual terms this means a largely handmade or masonry biennale – an earthy show dominated by brick, ceramics, wood and rammed earth rather than steel, glass or pixels. (As the text accompanying a project by architect Anna Heringer puts it, “Three billion people on this planet live in buildings made of mud.”) Formal novelty is largely sidelined – along with the broader notion of novelty as a shrine where architects ought to worship – in favour of an emphasis on place, climate and tradition.

In thematic terms, it means a show dedicated to the importance of incremental and bottom-up progress; what the north can learn from the south and the west from the east; and the value of cooperative or indigenous architecture rather than signature projects by the stars of the profession. Among the subjects that pop up in several corners of the exhibition are ritual; drones and their relationship to architecture and urbanism; and forensics and evidence.

Its critique of global markets and state surveillance, mixed with occasional post-apocalyptic scenarios, is a blend of Edward Snowden, Thomas Piketty, Naomi Klein and George Miller’s 2015 version of Mad Max. There are echoes of the 2007 Cooper-Hewitt exhibition “Design for the Other 90 percent” and the 2004 Bruce Mau book and museum show Massive Change.

The British pavilion, overseen by Shumi Bose, Jack Self and Finn Williams, is an experiment in redefining residential architecture in terms of time rather than space. It includes full-scale mock-ups of apartments designed to be lived in for a few hours or months – there are the borrowers again – as well as a few years or decades.

Even better is the Belgian pavilion, produced by the firms De Vylder Vinck Taillieu and Doorzon and the photographer Filip Dujardin. Linked in spirit to Aravena’s interest in unpretentious as opposed to preening beauty, it begins by asking if “bravura” architectural effects are still possible in cities struggling since 2008 with austerity and scarcity.

The answers are not what you’d expect. In displays by 13 contributors, including Stephane Beel and Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen, the pavilion combines experiments in remaking existing buildings in physically crude but poetic ways with digitally manipulated photographs by Dujardin of buildings with no apparent function.

Some architects – some architects left out of the show, that is – complained in Venice that what Aravena has produced is little more than a politically correct biennale. It’s true that the only way this exhibition is likely to give offence is by its reluctance to give offence.

Yet the tone is more tolerant and curious than strident or doctrinaire. Ultimately, the PC charge is a caricature, a reflection mostly of the anxiety of a Western architectural elite realising that its influence is waning even in Venice, the place it has long gathered every two years to toast itself.

Los Angeles Times