Christian missionary Jackie Pullinger’s 50 years of helping Hong Kong addicts beat drugs – and find God

Christian missionary Jackie Pullinger has been helping Hongkongers kick their addictions through prayer since 1966. It’s gone quickly, she says, and she feels lucky to have realised her dream

In the centre for recovering drug addicts run by the St Stephen’s Society in Sha Tin, about 20 Chinese men of various ages stand in a circle singing gospel songs. The youngest, wearing pyjamas and a coat, sits on a sofa hunched over his songbook, looking pained. He is in the first stages of withdrawal.

A middle-aged man puts his arm around his shoulder, offering solace.

The men are the latest among the thousands of Hongkongers that Briton Jackie Pullinger has helped quit drugs without the use of medication since she arrived in the city, by boat, in 1966. They may not succeed initially, she says, but once they have fully accepted Jesus’ help they become “like a newborn baby”, starting their lives afresh.

“Churches tend to look after the nice people. I do my work with the nasty ones, like addicts and prostitutes who feel despised and excluded,” she told the Post in January 1983. “They won’t go near churches, so I make it my job to find them.”

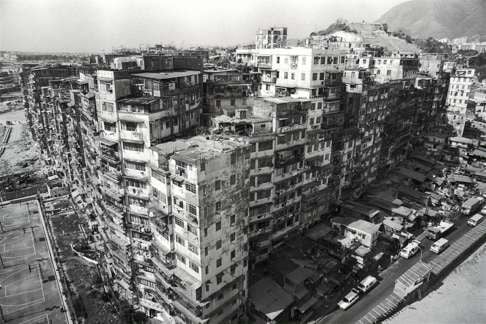

The golden jubilee of Pullinger’s arrival in Hong Kong, and the good deeds she has done, were recently celebrated at the Vine Centre in Wan Chai, and a three-day public worship begins at 6pm on Friday at Kowloon Walled City Park.