What Hong Kong needs to do to recycle more: sort waste properly and see it as a chance to make money, not a problem

City’s landfills are nearly full, yet the proportion of solid waste recycled has plummeted; people in the business say solutions start with seeing waste as a business opportunity

Cynics might find it ironic that the prestigious World Recycling Convention would be held in a city with such a poor record on the matter. Yet more than 900 recycling industry professionals from around the world – from traders, processors and brokers, to technology suppliers and consultants – gathered at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre in Wan Chai for the event last month.

“This is the business end of recycling, and there is so much happening in this region,” says Ranjit S. Baxi, president of the convention’s organiser, the Bureau of International Recycling. Whether his observation applies specifically to Hong Kong, however, is another matter.

About 98 per cent of the city’s recycling is carried out outside Hong Kong, and despite record levels of municipal solid waste (currently 1.39kg a day per resident) being dumped in landfills that are brimming to capacity, recycling rates are dropping like a stone.

Environmental Protection Department figures show that total municipal solid waste recovered for recycling in 2010 reached a modest peak of more than 3.5 million tonnes, but by 2015 had dropped by more than 40 per cent to a little over 2 million tonnes.

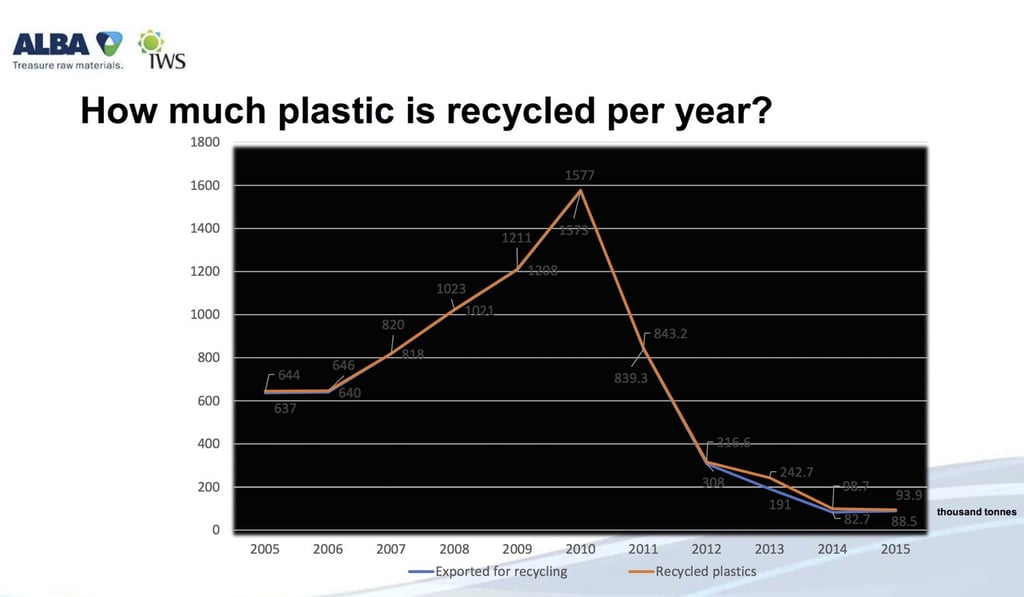

The track record on plastic, which accounts for 22 per cent of rubbish dumped in landfills, is even worse. Recycling of plastic peaked at 1.57 million tonnes in 2010, but has been dropping sharply and is now at such low levels (less than 90,000 tonnes) that it’s questionable whether it’s worth bothering at all.