Why Shanghai is perfect launch pad for creative women entrepreneurs

Women designers, architects, restaurateurs and other creatives are starting businesses in the Chinese metropolis and benefiting from its can-do attitude and lack of glass ceiling. We talk to some of these go-getters

When it comes to leisure lifestyle and creative start-ups, Shanghai is undoubtedly China’s holy grail. The metropolis of 24 million people is a cultural melting pot that continues to grow, and a notable feature of the boom is the great number of women leading the way.

“The market is much less saturated in Shanghai, especially for female designers/architects and young creatives,” says Hickling.

“In general we feel that in China, people are indifferent to what sex we are,” says Mok.

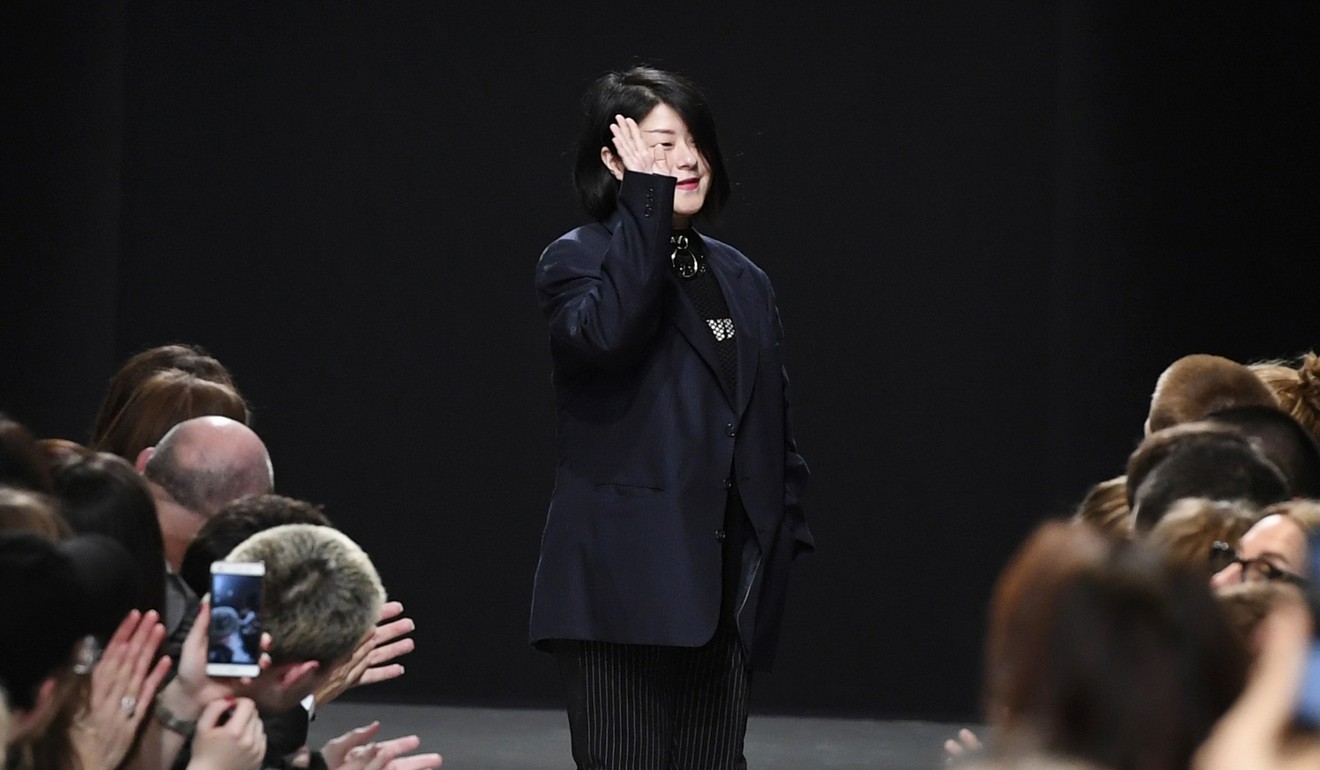

“There are a lot of female designers at the helm of Chinese brands now,” says the Central Saint Martins graduate, who founded her label in 2008 and has noticed a boom in the number of female entrepreneurs in the country.

“Women have really been leading [fashion] companies. Right now, I don’t think there’s any discrimination,” says Ma, whose plan to roll out 80 stores in five years is set to make her a household name in China.

The Shanghai designer who wants to shake up China’s lingerie industry

Many other Shanghai-based labels, including Uma Wang, Fake Natoo, La Vie by Ji Cheng, Helen Lee, Chloe Chen, Comme Moi, By Fang and Missy Skins, are run by women, and most are led by female creatives and directors. On the Paris Fashion Week womenswear schedule starting this month, by contrast, only about a third of the brands on show have female creative directors on board, and female CEOs or directors are distinctly few and far between.

“Being a ‘girl boss’ here? It is a very accommodating place,” says American Camden Hauge, a serial F&B start-up figure. She founded Shanghai’s popular SupperClub, hosting ticketed, one-off dining events, and brunch spot Egg. More recently she established a creative-led events/production/F&B company called Social Supply, partnering with Hongkonger Olivia Mok.

“I haven’t noticed any of the pressure or discrimination that I would imagine peers must feel in other markets,” says Hauge. “I think female leaders are really celebrated here, and there’s a good network of people who support that.”

Both in their late 20s, Hauge and Olivia Mok (no relation to Alex) started Social Supply just last year. Within the first few months the model had proven popular and disruptive, cultivating an enviable client roster, including Nike, Balmain, WeWork co-working spaces and Aman Resorts. The duo have become the darlings of the city’s F&B start-up scene, and will be hosting a one-off SupperClub event in Hong Kong on September 29.

The future of Chinese fashion according to Xiaoqing Zhang, the model-turned-designer behind Shanghai label X.Q.Zhang

Even among industries that aren’t yet dominated by women in Shanghai, being female isn’t a disadvantage. “There are not many [design] companies like ours in China that are run by young, foreign females,” says Linehouse’s Mok, “but it’s something that we turn into a positive when we’re talking about our positioning ... and we can create something really bespoke in terms of our design language for clients.”

Most successful Chinese womenswear labels are female-led, designer Ma notes, suggesting that it may be because they are “more energetic, more dynamic”, and “more realistic about what they [as women] want to wear”. A more personal approach to design and creativity when women design for women means that these brands are becoming first-rate at “delivering great things for our daily lives – and it’s about creating a lifestyle rather just selling garments”.

Shanghai’s latest creative and commercial boom has been making global headings, and this feeds the success of both male and female entrepreneurs. Ma, Hauge, Hickling and both Moks mention the new modern studios, creative workshops, hospitality places and shared offices that have sprouted in the past few years.

Jiang Qiong Er: a designer with a mission for tradition

“There’s definitely a huge start-up culture here. People are very entrepreneurial and innovative,” says Social Supply’s Mok, who since arriving five years ago, has seen a flood of new companies arrive on the scene. It’s not surprising though, she says, because starting a business is easier in Shanghai than in most cities. “The opportunities are bigger and some overheads are cheaper than in, say, Hong Kong.”

Growth has been rapid and organic for the Social Supply duo, spurred on by an onslaught of new clients and novel demands. They’ve excelled at creating engaging social events for Western brands to tap an affluent/aspiring Chinese market. The well-connected pair also host the large, biannual Feast food festival.

“Meeting the right people and forming a good network can make things so much quicker and smoother,” says Olivia Mok. “Shanghai has treated me very well, and it really helps that I’m from Hong Kong and speak Mandarin.”

The Linehouse pair reel off a list of fellow female entrepreneurs they like to support: Kelley Lee, who is constantly opening new F&B concepts combining Eastern and Western influences; Jenny Gao, who started Sichuan Supper Clubs; and the Social Supply women.

Although there’s often competition and overlap between start-ups, an appetite for the new is so fierce that many entrepreneurs argue there’s more collaboration than protectionism. Shanghai, Hickling says, is brimming with innovation and entrepreneurs “who are bringing concepts that didn’t exist in China before”. And because it is the country’s most international city, home to the most foreign residents, there’s a natural captive market for new concepts.

“It has an interesting relationship with the West. It’s probably one of most receptive cities in China for adopting new ideas,” Alex Mok says.

With the increasingly wealthy, Chinese middle classes on the doorstep as well – plus a young, international talent pool – there’s plenty of room for growth for young businesses. Couple all that with the city’s long history of international influence (including British, French, American and Jewish) since the opium wars and the Treaty of Nanking in the mid-1800s, and the result is a natural breeding ground for a cosmopolitan commercial and creative scene. Industries fusing East and West have long thrived here.

Speed and scalability help drive success. In Britain, where Mok worked for eight years before moving to Shanghai, it’s much harder and more time consuming to get things done as an architect/designer. “There’s so much paperwork; people are very conservative and risk adverse with projects before actual building starts. It’s different in China,” she says.

For example, Linehouse designed a small streetwear store called All SH. The client immediately liked the first concept presented, so they quickly enlisted their regular contractor, who priced the project from a 3D model and plan. Demolition of the old shop site started days after the concept was signed off, and the new store opened in just two months.

“There’s fluidity to the process here. Unexpected things always arise, both good and bad,” Hickling says. “China can be chaotic at times, but if you can harness its possibilities, the opportunities can be really open.”

On the other hand, Social Supply’s Mok cautions, “Everything moves so fast here and there’s lots of change. Shanghai is great, but there’s also lot of talk in this city. Sometimes things don’t end up being done, or they last a very short time. The survivors are those who are diligent.”