Why public book sharing hasn’t taken off in Hong Kong, and what that says about city’s street life and appetite for reading

Book crossing, or leaving books in public places for people to read, is popular in Singapore, Taiwan and elsewhere, but in Hong Kong bookcases placed on streets have been removed by government workers or stolen; a few do thrive, though

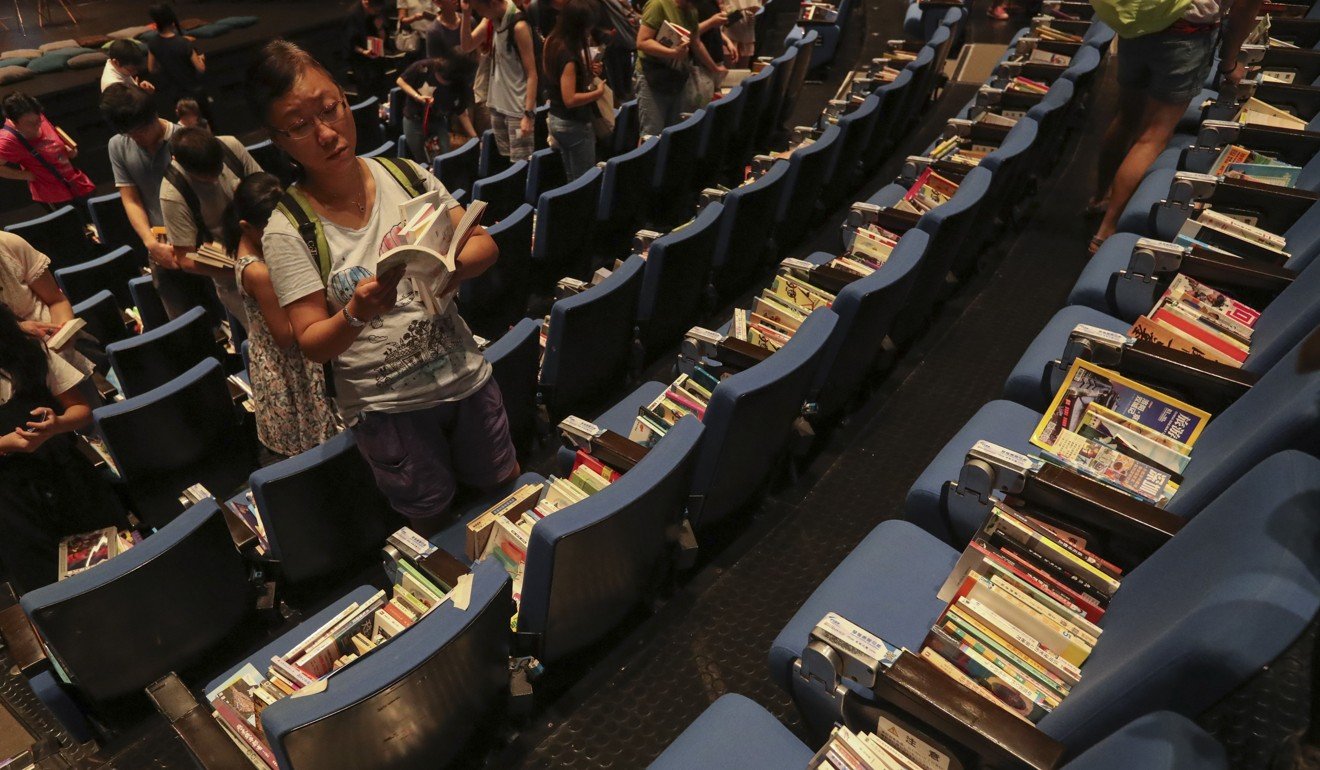

Bookworms drift along seat rows, slowly scanning book titles and occasionally picking one up to take home. About 2,300 people attended the seventh annual Book Crossing Festival last month at Youth Square in Chai Wan, where more than 8,000 books were available for exchange over two days.

Book crossing, or book exchange, means leaving a book in a public place – not at an organised event – to be picked up and read by others, who then do likewise. It’s not as established in Hong Kong as it is across Europe and in other Asian locations such as Singapore and Taiwan, but it has been slowly taking root in the city.

In April this year, officers from the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department removed a bookcase from the pavement in Centre Street in Sai Ying Pun. It had been collectively maintained by residents as part of a citizen-led initiative to promote community building and freecycling.

Make reading a joy not a chore, Hong Kong parents and teachers urged

Neighbourhood resident Tsui Ho-yee recalls how, two years ago, a group of students organised the initiative as a social experiment after seeking the opinion of residents. The bookcase was warmly received and it remained on the street after the experiment ended.

As a society we have been taught that we cannot occupy space that is not ours ... But sometimes, people have to challenge this convention

Tsui, who lives in Third Street and works in High Street, says she keeps a careful eye on the bookcases and will take the books home when it rains.

Sai Ying Pun’s public bookcases have played a role in fostering a sense of community spirit in the district, Tsui says.

“It’s just like parents with children. Even when we don’t have things to talk about, we have things that we own together.”

As well as books, items ranging from food to electrical appliances have been shared on the bookcases, she adds.

Booming book sales in India a sign of the good times

The sudden removal of the first bookcase in Centre Street shocked and angered Tsui and many other residents. She feels the government does not understand their relevance to the community. Officials said the removal was a response to two complaints that the bookcase contained “publicity material not authorised to be displayed in a public space”.

“There is a lack of platforms for reading in Sai Ying Pun because there’s no public library in the area,” Tsui says. The government had not considered the potential of the bookcase as a tool for promoting reading, she adds.

Some see Hong Kong as something of a cultural desert, its residents relatively uninterested in the arts and culture. A survey conducted by the Hong Kong Publishing Professionals Society in 2015 found that Hongkongers read two books a year on average. This compares to 11 books in South Korea and nine in Japan, according to a report the same year by the China Press and Publication Academy.

Science fiction’s new golden age in China, what it says about social evolution and the future, and the stories writers want world to see

Book lover Simon Li Kin-man says the annual book crossing festival is too short-lived to foster a culture of reading. “It’s just two days, then it’s gone,” says Li. He suggests encouraging book crossing in more public spaces, where people can sit down and read, such as bus stations, parks, cafes and even dental clinics.

Li first encountered book crossing in Taiwan three years ago when he got on a bus with a bookcase on board. He saw a boy take a book and spend the whole journey reading it.

“Through book crossing, a person can come across books that they would otherwise not have read,” Li says. “You will have a wider choice of books and perspectives. The reason there are so many conflicts in society today is that people always think their own perspective is the correct one. This is probably because we read too little.”

Reading books may add years to your life, but news articles don’t count (... sorry)

Li blames the removal of the bookcase on Centre Street on Hongkongers being accustomed to public spaces being diligently managed and maintained: “The hygiene? The safety? Will it block people?” Li thinks the government should consider a way to allow book crossing to flourish within such limitations.

Books are nourishment for the mind, and are an element of a civilised society. Everyone should have the chance to read

Book crossing activities are emerging in other districts of Hong Kong. Terence Tong Kin-fung, 23, set up the Kai Fong Library (Kai Fong meaning neighbourhood association) with friends last year in Tin Shui Wai, in the northern New Territories.

Tong was inspired by an online post about book crossing in the United States. In January 2016, Tong and his friends placed a bookcase at a bus station in Tin Shui Wai to test the reaction of residents – which was positive. The following month, they started temporarily placing bookcases in other parts of the new town, including light rail stations and parks. Currently, they are tending just one bookcase, at a pavilion near Tin Shui Estate.

But Tong says many Hongkongers are unfamiliar with the book crossing concept, and may have misunderstood their intentions. Kai Fong Library’s bookcase has been taken away or destroyed many times. Tong suspects people either suspect it’s a piece of rubbish that’s been thrown out, find it attractive and take it away, or just remove it out of mischief.

“Most Tin Shui Wai residents need to go to work early and they return late, but the opening hours of the library do not account for this,” Tong says. He believes public bookcases, by contrast, can better serve people. By placing the Kai Fong Library bookcase at the pavilion, it is accessible to many residents as they go about their daily routines, including joggers who stop for a rest, and the elderly who hang around at the pavilion sun-drying orange peel.

Why it wouldn’t take much for China and Japan to go to war – new book Asia’s Reckoning explains

The public bookcase gives residents greater freedom to develop their reading habits, Tong believes. “There is no time limit for reading. You can decide your own reading pace,” he says.

“People often have the impression that Tin Shui Wai is a dull and boring district. Time passes particularly slowly here,” Tong says. He hopes book crossing will bring more colour to residents’ lives. He also wants to build a sense of belonging among residents through book crossing. “We want to use books to bridge the gap between residents,” he says. Tong hopes to see residents who stop for bookcrossing having conversations, and forming stronger bonds.

“Ideally, we hope every district in Hong Kong can have its own book crossing library,” Tong says. “Then the habit of reading in Hong Kong would be enhanced.”

He acknowledges that Hongkongers are generally criticised for not reading enough, or going to the annual Book Fair simply to “check in” on Facebook and show off to their friends where they’ve been.

“Books are nourishment for the mind, and are an element of a civilised society,” Tong says. “Everyone should have the chance to read.”

Despite his belief that not enough is done to encourage reading in the city, Tong believes Hongkongers do enjoy reading. “But it requires time to build the habit. Why don’t we spend more time and effort to create the right atmosphere to promote reading?”