China’s key role in international fight to save one of rarest birds in the world from extinction

A wetland in Jiangsu province – a vital stopover for the spoon-billed sandpiper on its migration south from Siberia – needs protecting against development, one of a number of threats to a species with under 250 breeding pairs left

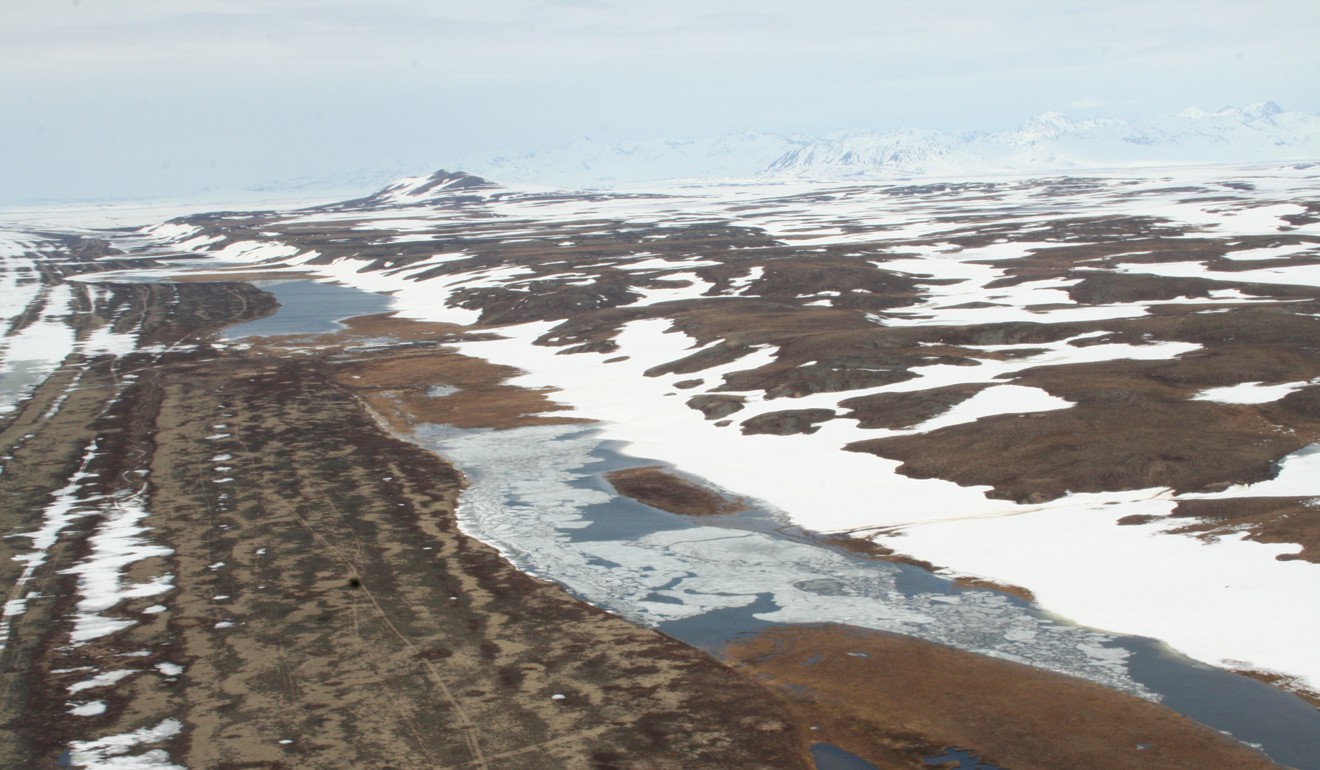

Pavel Tomkovich spent the summer 300 kilometres below the Arctic Circle in Chukotka, an isolated coastal region of northeastern Siberia. Each day he packed hand-held flares and a pepper spray as protection against bears, and set off into the wilderness in search of a critically endangered bird – the spoon-billed sandpiper.

Tomkovich, head of the ornithological department of Moscow State University’s Zoological Museum, is part of the international Spoon-Billed Sandpiper Taskforce, involving Russia, China and a number of other countries fighting to save the species from extinction. With numbers falling from an estimated 1,000 breeding pairs at the turn of the millennium to fewer than 250 pairs in 2014, the taskforce is hoping efforts will lead to a 50 per cent increase in the population by 2025.

Pet trade is driving Indonesian rare birds dangerously close to extinction

There are concerns among conservationists, however, that despite a raft of measures introduced to protect the species, probably the most important stopover for the species on its migratory route south in winter – in China’s Jiangsu province – is an unprotected wetland at risk of development.

The spoon-billed sandpiper is a shorebird with a distinctive spatula-like bill. It feeds on worms, crabs and clams in muddy, shallow coastal waters.

Every summer, the birds return to Chukotka from South and Southeast Asia to breed in Siberia under the watch of Tomkovich and his team. “Three or four eggs are usually produced. Females stay with their new families for several days before migrating southwards, leaving the chicks to be cared for by the males,” Tomkovich says.

“We search for birds, their nests and newly laid eggs. We attach identification flags to the legs of adults and chicks in order to study their migratory routes.”

In 2013, a female spoon-billed sandpiper was banded with a green flag and the number 05. “Green 05”, as this bird is now known, has been part of a project to save the species ever since. Returning to Russia annually, she is the only survivor from eight birds identified and tagged that year.

Since losing her first mate, she has nested with the same male since 2014, and their offspring have been taken for “head starting”. This involves Chukotka-based conservationists gathering and incubating the eggs, and nurturing the hatchlings, safe from predators, until they are old enough to fly. Some eggs – included ones laid by Green 05 – have been used for a captive breeding programme run by conservation group the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust in Britain.

From poacher to ranger: saving China’s Siberian tigers

Attaching leg flags to spoon-billed sandpipers has enabled researchers to identify where the birds travel to avoid the harsh Siberian winter. If the efforts in Russia are not to be wasted, however, all landing sites along the bird’s migratory route need to provide sanctuary for the rare wader.

Sightings show Green 05 journeys 8,000km to Thailand, with a crucial three-month stopover at the Tiaozini mudflats in China’s Dongtai county, 100km north of Shanghai in Jiangsu province. On the wide open mudflats, Chinese and international birdwatchers reported Green 05’s arrival at the end of September.

“Tiaozini is the route’s most important stopover but is unprotected by law,” says Nigel Clark, scientific adviser to the Spoon-Billed Sandpiper Taskforce. He is concerned about proposed land reclamation and development of the area into an industrial new town.

According to research to be published in the journal Bird Conservation International, Tiaozini hosts much of the stopover population as the spoon-billed sandpipers head south. “The birds cannot go elsewhere. If the development goes ahead, Green 05 and many others will not survive,” Clark says.

Another resting place for the birds – on the return route to Siberia – is Hong-Kong’s Mai Po Marshes Nature Reserve.

Chinese rare bird poacher uses females as bait

“Records began in 1957, and today a few birds visit in spring on their return to the north,” says Fu Wing-kan, assistant manager of the China Programme at the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society. “Maybe more will pass through Hong Kong if conservation elsewhere is successful and spoon-billed sandpipers survived in greater numbers,” she adds.

Clark and Professor Chang Qin of Nanjing Normal University have begun using satellite technology to map the birds’ exact flight paths, and raising awareness about their plight among local communities.

“It’s challenging and strenuous work, like trying to find a needle in a haystack. We had to catch, then release 1,000 birds just to tag three spoon-billed sandpipers,” Clark says.

The tiny satellite devices, each costing US$5,000, are tracked with a computer program, and the effort has been paying off. Data shows the birds migrate on from Tiaozini, along the southern coast of China, stopping in Fujian and Guangdong provinces during the autumn. One bird completed a 48-hour non-stop flight southwest to Myanmar’s coast.

Clearer information about where spoon-billed sandpipers rest helps target areas where conservation efforts are needed. Subsequent land-based surveys in Fujian, for example, showed that widespread mist netting threatened the birds.

Clark says they found “very fine nets for catching flying birds, used legally for research but also illegally to catch birds to be sold as delicacies. Spoon-billed sandpipers are not the hunter’s target, but any caught in the nets are likely to die.”

After the mist nets were reported, the authorities removed them and erected signs to discourage the practice, he says.

Jing Li, fundraising and community operations director for Jiangsu-based community organisation Spoon-Billed Sandpiper in China, says the group reaches out to local schools, businesses and fisherfolk in the fight to save the birds’ Tiaozini habitat. Local residents were initially unaware that the mudflats were ecologically important.

On her visits to local schools, Li educates students about the species. “I hope they will then discuss this precious bird and its unique habitat with their families,” she says.

Li plugs into parental concerns about a safe, healthy environment for children, and their concerns about struggling livelihoods that depend on the mudflats.

More than a third of Hong Kong shark fin products are from threatened species, study reveals

“People traditionally harvested hard clams and seaweed. We share an interest here. Conservationists wish to preserve the mudflats, while fisherfolk wish to continue their way of life,” she says. “Locals sympathise with the birds, but have noticed unexplained and falling clam and seaweed yields in recent years.”

To make ends meet, locals are raising crabs in new, deeper ponds, which spoon-billed sandpipers do not use. Li is working with locals and international NGO the Aquaculture Fisheries Council to set out criteria for certifying sustainably sourced seaweed and clams.

It’s challenging and strenuous work, like trying to find a needle in a haystack

“The idea is in its infancy, but they could sell at premium supermarkets in Shanghai or Beijing, even Japan, generating a higher income for the community,” she says. “Protecting the livelihoods which depend on the mudflats allows us to preserve the spoon-billed sandpipers’ resting site.”

The fight to save the spoon-billed sandpiper is also dependent on the situation in Thailand – Green 05’s final destination. Thai birdwatchers sighted the traveller on the coastal salt pans of Khok Kham, southwest of Bangkok, on October 31.

“Generations-old methods have been used to produce sea salt here. The salt ponds provide perfect feeding grounds for the birds, but with salt prices low, the industry is in trouble,” says Philip Round, associate professor of biology at Thailand’s Mahidol University, and an expert on the area. Today, there are only 28 salt farming families in Khok Kham, compared to about 300 in the 1980s.

“Reluctantly, people convert their land into prawn farms. It’s easy money, but not suitable for spoon-billed sandpipers,” explains Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok, public relations manager for the Bird Conservation Society of Thailand. “Many families own and feel connected to their land. They are keen to preserve their way of life.”

Last year, the community raised the alarm over construction of a solar panel farm on a section of the salt pans, which would destroy the spoon-billed sandpiper’s habitat, and the society campaigned to halt the work.

‘It was like a mini wildlife park’: Chinese police bust smugglers selling red pandas and gibbons online

“Developers started without permission. We pointed out that Khok Kham is legally protected as nationally important wetland, designated for agricultural use only,” Ayuwat says. “Building work ceased when authorities refused to grant a proper licence. No one really won, as the land is damaged.”

Green 05 is one of two tagged birds recorded at Khok Kham; more spoon-billed sandpipers land further down the Thai coast, where conservation efforts continue. The majority head for Myanmar or Bangladesh, where conservationists are also working to safeguard the species.

Can Taiwan’s Formosan clouded leopard claw its way back from extinction?

The success of the breeding programme in Russia relies on efforts in other countries, with China playing a key role. Saving the spoon-billed sandpiper, as Green 05’s long journey shows, is a truly international task.