Stories behind Hong Kong districts: Tsim Sha Tsui – the beach that reached to become a major tourism and shopping hub

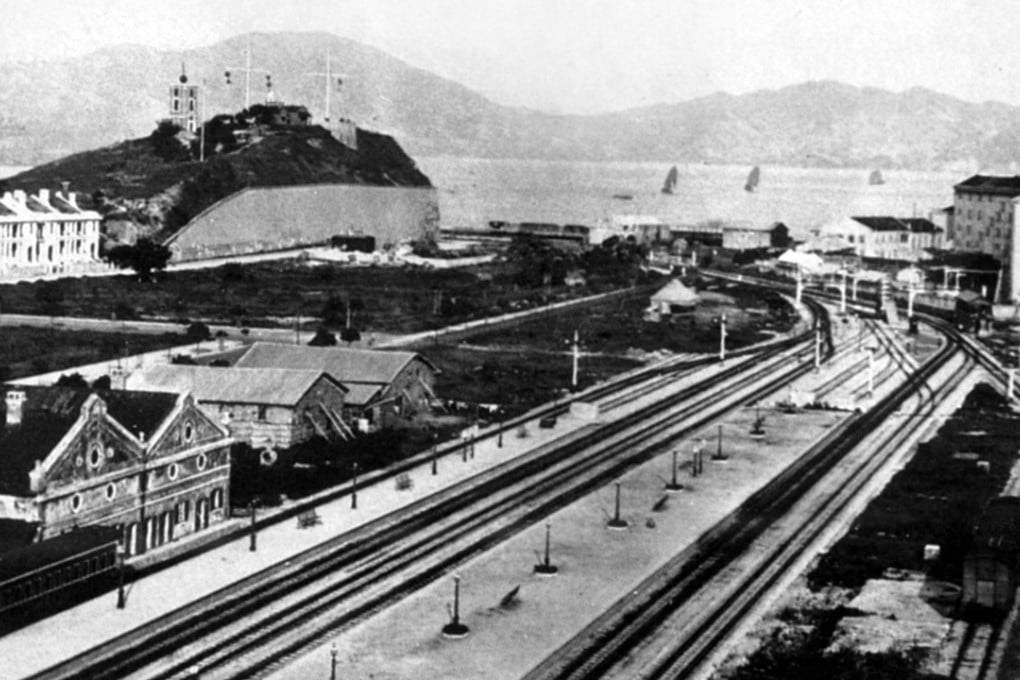

Its name means ‘sharp sandy point’. Earmarked as a port, development sped up with the Kowloon-Canton Railway’s arrival; later rapid urbanisation left little of the local flavour. One structure, though, has escaped the wrecking ball

In 1860, a small ritual took place at the southern tip of the Kowloon peninsula – then a largely undeveloped area of Hong Kong with only a handful of scattered villages – that would forever change the area’s fate.

A Chinese magistrate scooped up a handful of soil, sealed it in a bag and handed it to a British representative. With that symbolic gesture, the peninsula was ceded to Britain under the Convention of Peking, 19 years after Britain had taken control of Hong Kong Island.

Stories behind Hong Kong districts: Mei Foo Sun Chuen, where middle-class dreams began

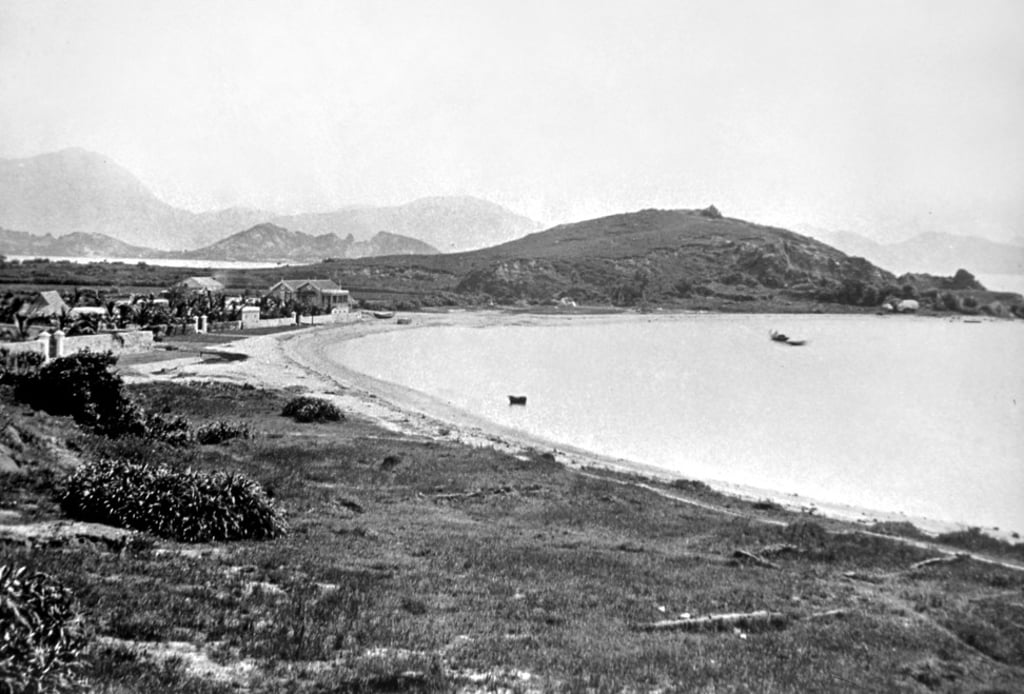

Looking at Tsim Sha Tsui today – a major tourism, shopping and dining hub – there is no evidence to suggest how it got its name, which literally translates to “sharp sandy point”. But the beach, whose shape inspired its name, was captured in a photo taken 10 years after Kowloon became an occupied territory – possibly the earliest photo taken of the area, according to local historian Ko Tim-keung.

From there, timber of the fragrant Heung tree that gave Hong Kong its name – which in English means “fragrant harbour” – was shipped to Hong Kong Island, then on to Canton (now Guangzhou) and the rest of the world.

The colonial government had seen the potential for Tsim Sha Tsui to become a major commercial port early on. Being the peninsula’s closest point to Hong Kong Island, it was strategically located, with deep water that would allow even large clipper ships to drop anchor.