The internet was born with two major flaws, says one of its ‘fathers’, Vint Cerf

- When the internet started, its inventors had no idea how big it would become

- As a result there were not enough IP addresses and secure transmissions weren’t possible

The internet was born flawed. But if it hadn’t been, it might not have grown into the worldwide phenomenon it’s become.

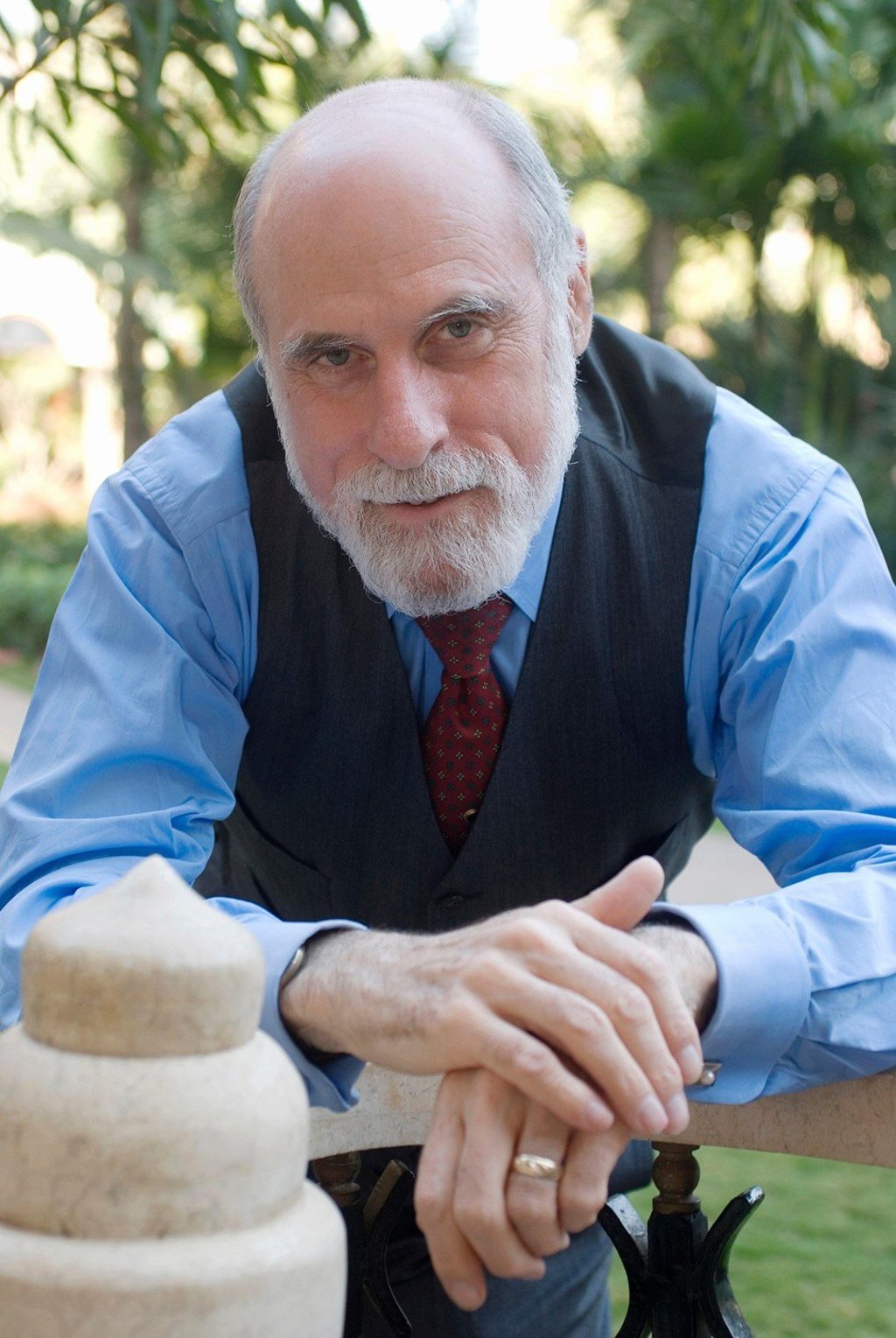

That’s the take of Vint Cerf, and if anyone would know, it’s him. He’s widely considered to be one of the fathers of the international network and helped officially launch it in 1983.

When the internet debuted, Cerf, who is now a vice-president at Google and its chief internet evangelist, basically didn’t set aside enough room to handle all the devices that would eventually be connected to it. Perhaps even more troubling, he and his collaborators didn’t build into the network a way of securing data that was transmitted over it.

You might chalk up the lack of room on the internet, which was later corrected with a system-wide upgrade, to a lack of vision. When Cerf was helping to set up the internet, it was a simple experiment, and he couldn’t really imagine it getting as large as it became.

The security flaw, on the other hand, can be chalked up, at least in part, to simple expediency, Cerf says.