Robot marine plastic pollution collector Hong Kong students invented offers a cheap solution to clear rubbish-choked coasts

- ClearBot, prize-winning, solar-powered, semi-submersible rubbish scooper developed by Hong Kong students, uses open-source software and is easy to build

- Team behind it hope to develop commercial models they can sell, while making US$900 ClearBot design available to coastal communities in poor countries

Thousands of tonnes of plastic rubbish drift in the seas of Asia, the region environmentalists cite as the biggest source of the petrochemical waste that chokes coastal waters and leaves beaches looking like rubbish dumps.

Clearing up the massive piles of refuse is a never-ending task, but a new invention developed by Hong Kong student engineers and scientists could help to make a difference.

They have developed a semi-submersible robotic marine rubbish collector, which they have named the ClearBot. It was awarded second prize at the Global Grand Challenges Summit in London in September. Now they want to put it to good use to help tackle the intractable problem of marine plastic waste worldwide.

“This is a very prestigious international competition so it’s quite an achievement,” says project supervisor Dr Hayden So Kwok-hay, associate professor in the department of electrical and electronic engineering at the University of Hong Kong (HKU).

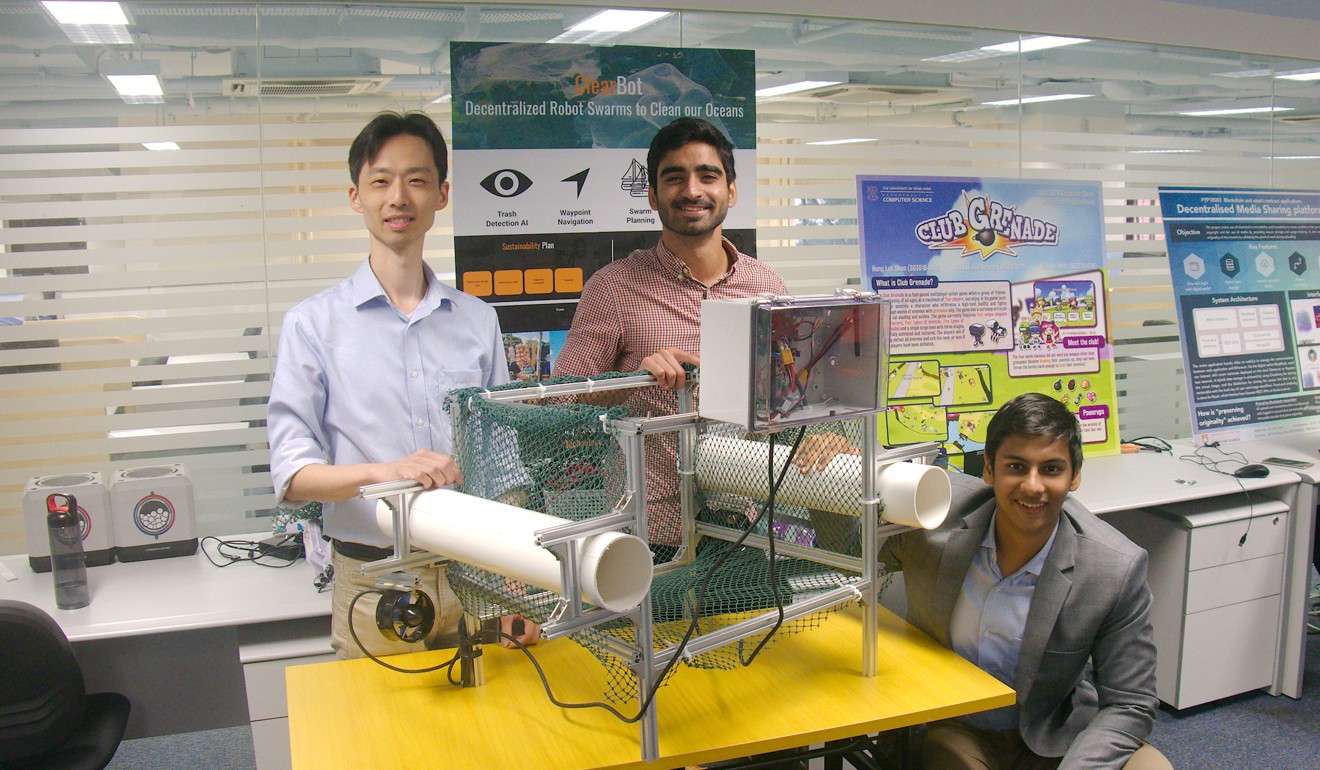

The award-winning device consists of a simple metal frame containing a rubbish collection basket and PVC pipes to provide buoyancy. It is controlled like a remote-controlled boat, with two battery-powered thrusters.

When the refuse is detected by artificial-intelligence object-recognition software, the ClearBot moves in to scoop it up in a semi-submerged collection net, guided by an inbuilt GPS system.

It can be operated by remote control, or programmed to follow a preset search path.

“We are using aerial drone navigation and putting it in a vessel,” says team member Sidhant Gupta, an HKU computer science graduate.

The core of the system is a waterproof electronics pod, and doesn’t need a metal frame but can be mounted on a simple plank of wood or bamboo frame, if that is the best solution for the local environment, he adds.

The judges were impressed not only with the technology that went into the ClearBot, but also the fact the system was designed to solve a global problem in a practical way and with the use of open-source technology.

Coastal communities in developing nations can access the software free of charge, come up with their own hardware solutions, and adapt the basic design to meet local conditions.

The system is also relatively cheap – the prototype’s components cost less than US$900.

The team reveals that the programme did not get off to an auspicious start.

“Two minutes into the first sea trial, a large wave knocked the ClearBot over and all our electronics were soaked,” Gupta says.

Plastic marine waste is a growing scourge in Bali, which for a long time has been a favourite holiday destination of Indonesians and international visitors.

“Bali depends on tourism, so the surfers pull the rubbish out of the sea every morning, just using nets towed behind their surfboards,” Gupta says.

Since there are no specialist electronics suppliers on the island, the team bought a few radio-controlled toy helicopters and used the rotor blades to power the vehicle. They tested the improvised method in their hostel’s swimming pool before putting the experimental ClearBot to work at sea, Gupta says.

“A bunch of locals were looking at the robot and they really liked it because they could deploy it wherever they wanted, rather than take a whole morning to clean the seas near the beach,” says fellow team member, Ahmed Abbas Alvi, a mechanical engineering student and product developer.

When I saw this system for the first time, I knew it was the one. We are not necessarily looking for Nobel Prize-winning scientific breakthroughs. We are looking for solutions that can help mankind

Following more promising trials in which the electronics did not become waterlogged, the prototype was pitched to So, who was assessing entries for the Hong Kong heats of the Global Grand Challenge.

“When I saw this system for the first time, I knew it was the one,” So says. “We are not necessarily looking for Nobel Prize-winning scientific breakthroughs. We are looking for solutions that can help mankind.”

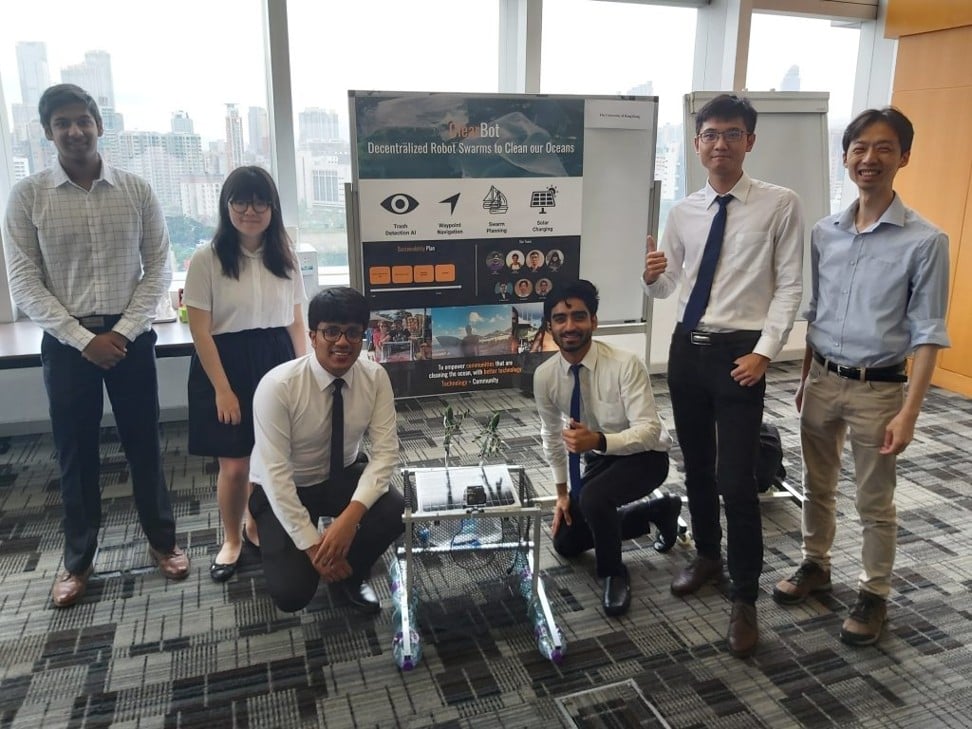

A larger team was formed under So’s supervision, with the two engineers joined by computer science undergraduates Angel Woo Chung-yu and Utkarsh Goel, as well as Ma Jiacheng from the faculty of science.

The team’s two key challenges were how to scale up and improve the simple robotic rubbish scooper, and devise a sustainable and charitable business model. That ultimately proved key to their success in the international competition in London.

“The idea is not just to make lovely shiny robots and sell them to the world,” So says. “It’s open source, so anyone can build their own robot and adapt it to the local conditions and scale of the job.”

He also approved of the team’s proposed business model. Revenue could be generated by building robots for port authorities and commercial customers, even as the open-source software offered advantages for communities in developing countries.

After winning the Hong Kong leg of the competition, the HKU team was joined by Padmanabhan Krishnamurthy from Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and Theresa Yip Man-yee from City University of Hong Kong to form a Joint University Team of Hong Kong and compete with other China-based teams on the world stage.

The cost of making ClearBots would fall if it can by manufactured in reasonable quantities.

“We are keen on getting this commercialised and economically viable,” says Gupta, who, since graduating from HKU this summer, has founded his own robotics and imaging company in Hong Kong.

With that in mind, the team members are now discussing a collaboration with the Hong Kong Maritime Museum, which is keen to encourage home-grown technologies that can offer solutions for cleaning up pollution in local waters.

“This looks like a very exciting, home-grown, hi-tech solution to the local problem of marine plastic pollution, which blights local waters and threatens marine life. As a maritime museum it is part of our mandate to encourage these innovations,” says museum director Richard Wesley.

The Marine Department of the Hong Kong government is tasked with collecting and disposing of rubbish in Hong Kong waters and said in its 2018 environmental report that “floating refuse is difficult to clear because it drifts with current and wind”.

Last year, the department collected 16,084 tonnes of trash, including 11,534 tonnes of floating refuse. It operates a fleet of specialised refuse collection vessels and about 80 contractor vessels to tackle the problem.

A system like the ClearBot is only part of the only solution to Hong Kong’s marine waste problem, however. Government studies show that 80 per cent of the rubbish in the city’s waters originates locally and on land. In all likelihood, only restrictions on plastic use onshore, and preventing plastic waste reaching the sea, will help end the blight of floating waste in the ocean and harbours and on beaches.

Often, however, beach clean-up volunteers and contractors are unable to reach rubbish floating in the sea. A ClearBot would allow them to do so safely. The ClearBot has already performed well in local waters, the design team says.

The ClearBot team aims to produce a user-friendly, polished commercial product, and the members believe they are close to achieving the goal.

“It’s not too far from reality,” So says.