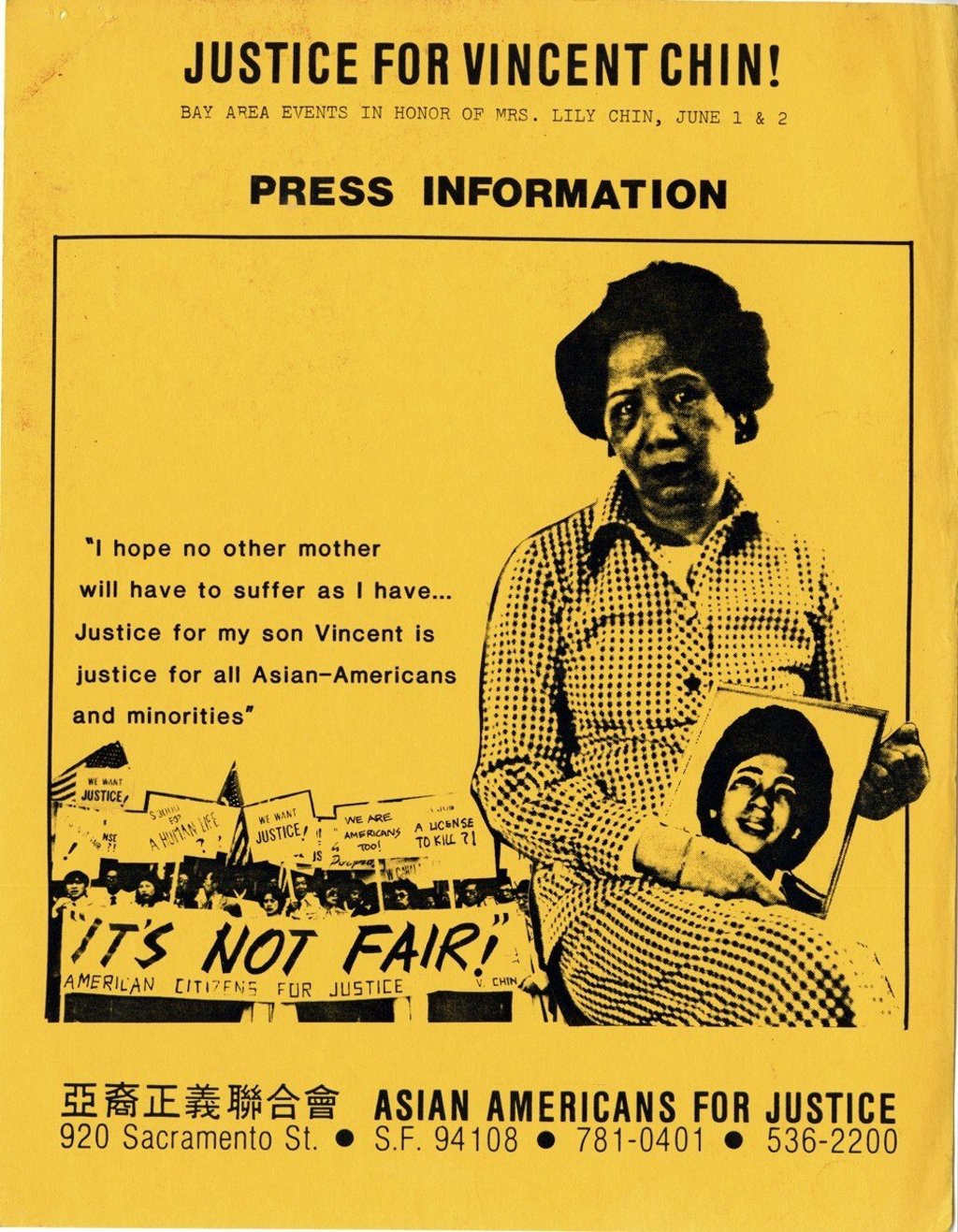

The 1982 killing of Vincent Chin was ‘the first time Asian-Americans came together’ to fight for justice

- Unusually for that era, his mother, Lily Chin, stepped forward to lead a fight for justice and ‘to show that no other mother should go through this’

- His death was a ‘turning point’, says a filmmaker close to the case, yet few recall it. ‘The American dream story. It’s not about Vincent,’ a museum head says

On the night of June 19, 1982, a Chinese-American man was celebrating his stag night with friends in the US automotive capital, Detroit, when a fight broke out.

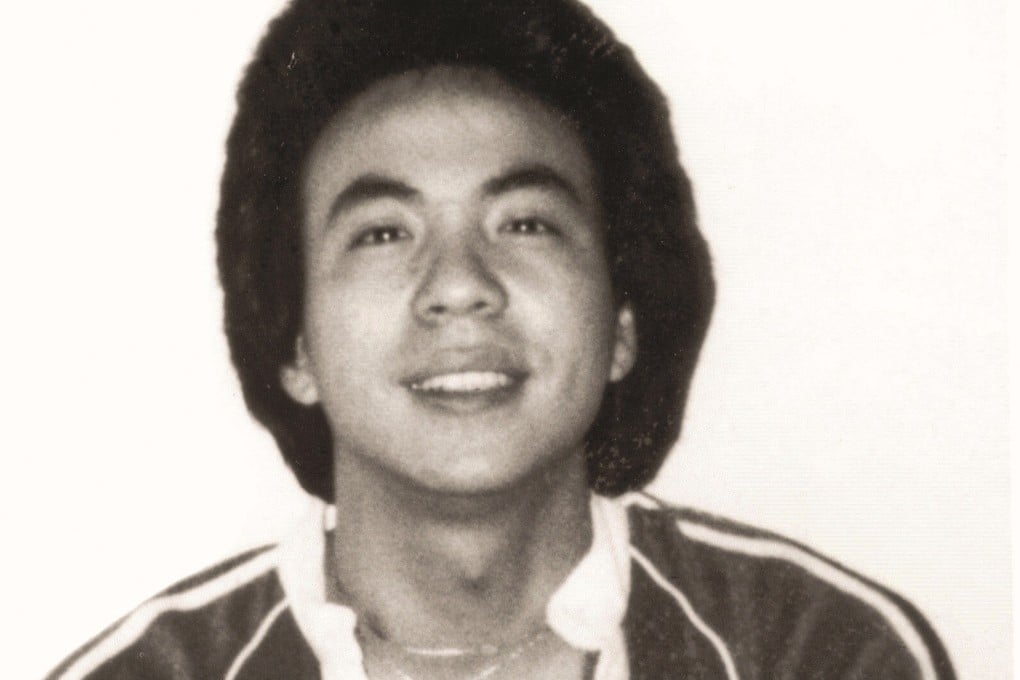

Enjoying a marriage custom of his adopted culture, 27-year-old draughtsman Vincent Chin was days away from beginning a new life with his fiancée. But he never made it home that night. And days later, the 400 guests invited to his wedding would instead attend his funeral.

Thirty-eight years ago today, June 23, Chin died in a hospital following four nights in a coma after he was brutally beaten with a baseball bat outside a McDonald’s in Detroit’s Highland Park neighbourhood.

“It’s because of you mother-f*****s we’re out of work,” one of his attackers, white Chrysler plant supervisor Ronald Ebens was said to have shouted, while taunting Chin in the car park of the Fancy Pants strip club. Ebens and his recently laid-off stepson Michael Nitz thought Chin was Japanese.

“Back then an American car was a status symbol the world over,” says Frank Wu, president of Queens College at the City University of New York. If you worked for a carmaker, “it was a job you had for life, with health care and a pension”. Wu, 53, grew up 20km (12 miles) from Highland Park.

By 1974, oil prices had quadrupled in the months following a decision by Opec, a cartel of major oil producing countries, the previous year to impose an oil embargo on the United States. It was an act of retaliation for the US administration’s decision to resupply the Israeli military during the Arab-Israeli War. The outcome, often referred to as the “economic Pearl Harbour”, effectively left the US car industry in crisis.