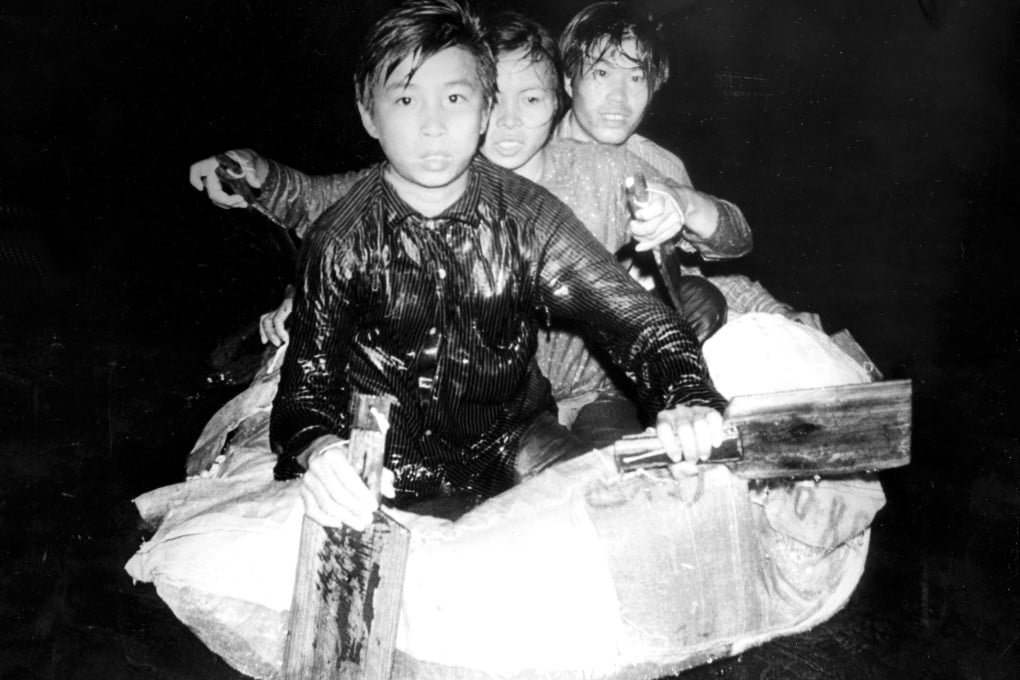

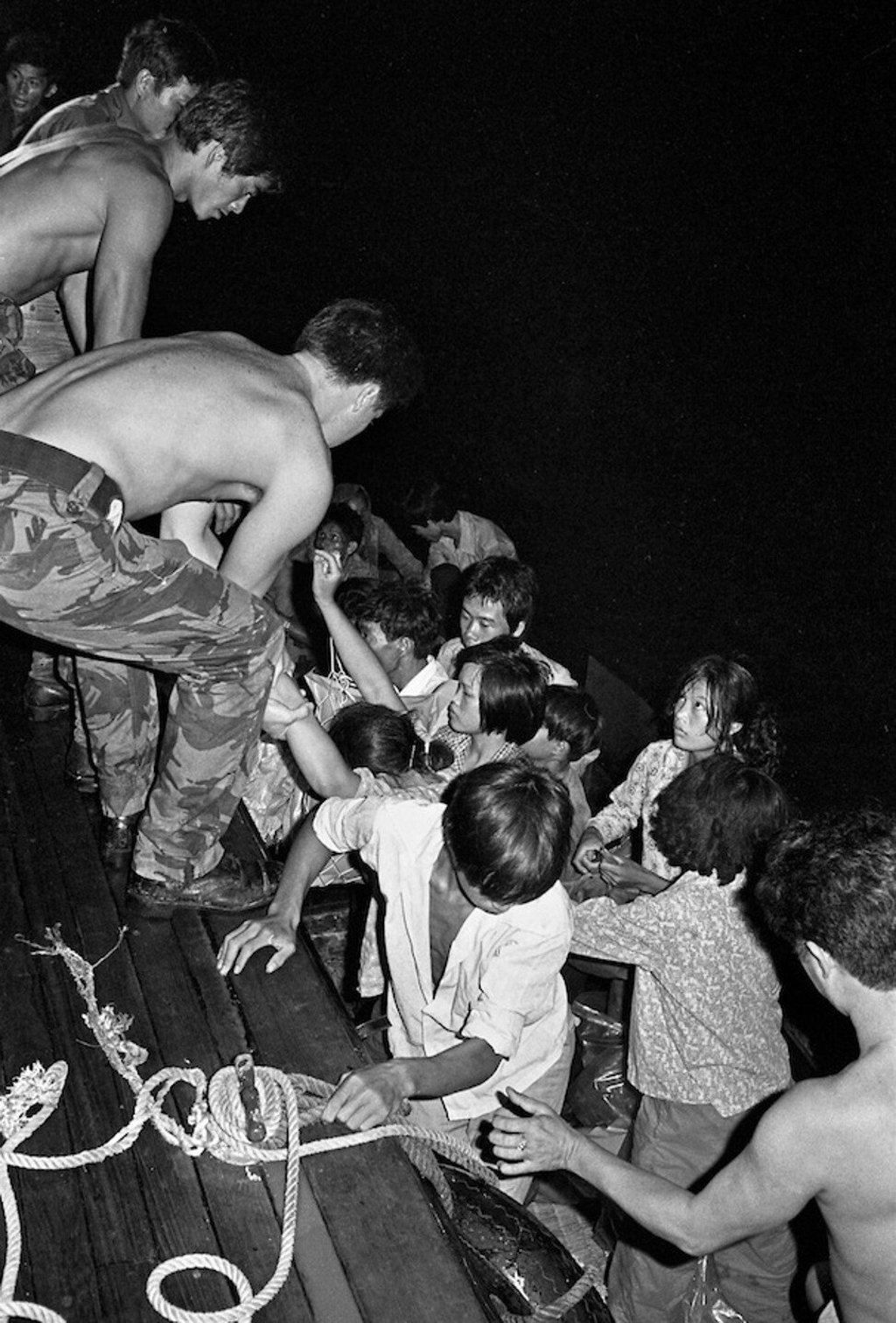

The great escape: how Chinese illegal immigrants to Hong Kong found a new life – if they could ‘touch base’

- Until October 1980, illegal immigrants from mainland China who made it as far as Boundary Street in Kowloon could register for Hong Kong residency

- A former soldier, interpreter, police officer and illegal immigrant recall their experiences of what was known as the ‘touch base’ policy

At the stroke of midnight on October 23, 1980, Hong Kong’s grown-up version of hide-and-seek ended – and it was game over for a huge number of illegal immigrants.

What became known as the “touch base” policy had begun in November 1974. Faced with a growing tide of illegal migrants from China, and concerned about the prospect of roving bands of undocumented entrants scraping a living in the seamy underbelly of Hong Kong, the British colonial government reasoned that if illegal migrants could make it across the Chinese border past the security forces and get as far as the city proper, they might as well be given a welcome.

Boundary Street in Kowloon was designated as the finishing line, and migrants who “touched base” there were registered and given an ID card. It wasn’t a perfect system, but nobody could think of anything better. In the policy’s final weeks, media commentators ranted about the prospect of a tsunami of “IIs”, as they were called for short, flooding the city’s housing and other facilities. As it was, the flood turned out to be more of a trickle.

As the clock ticked on the policy, key players – including a police officer, a Gurkha sergeant-major in the British Army, a military interpreter, and a determined illegal immigrant – went about their business.

Les Bird was a 27-year-old inspector commanding the Royal Hong Kong Police’s Small Boat Unit in Deep Bay on Hong Kong’s northwestern border.

“Deep Bay was not deep at all. In fact, when the tide was out you could practically walk across it, so the IIs came streaming across every night,” says Bird, who recorded his experiences in his bestselling memoir A Small Band of Men.