Last survivor of World War II prison ship tragedy dies aged 101 – his life before and after the sinking of the Lisbon Maru

- Briton Dennis Morley was one of hundreds of prisoners of war aboard the Lisbon Maru when it was sunk by a US submarine in 1942 en route to Japan from Hong Kong

- It was only many years later that Morley was able to talk about the traumatic experience. He died earlier this month after testing positive for Covid-19

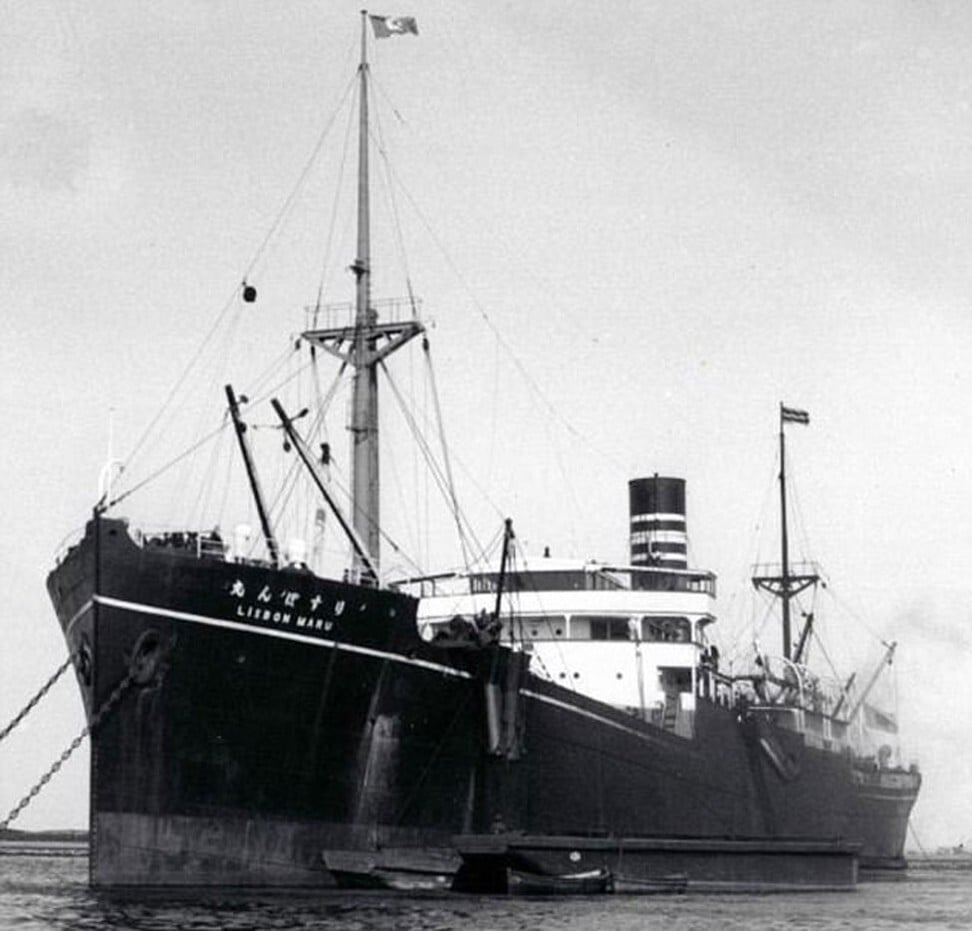

In 2006, when Briton Dennis Morley came to Hong Kong on one of several visits later in his life, there was talk of making a movie about the World War II sinking of the Japanese freighter, Lisbon Maru.

He had been on the ship with hundreds of other prisoners of war when it was torpedoed by a US submarine en route from Hong Kong to Japan.

Morley also visited Japan in 2006, a country that in modern times surprised him. He enjoyed spending time with Japanese youngsters and had been impressed when, visiting Kobe, he was looked after by the mayor.

Morley was the last known survivor of the Lisbon Maru and died at the age of 101 on January 3 after testing positive for Covid-19.

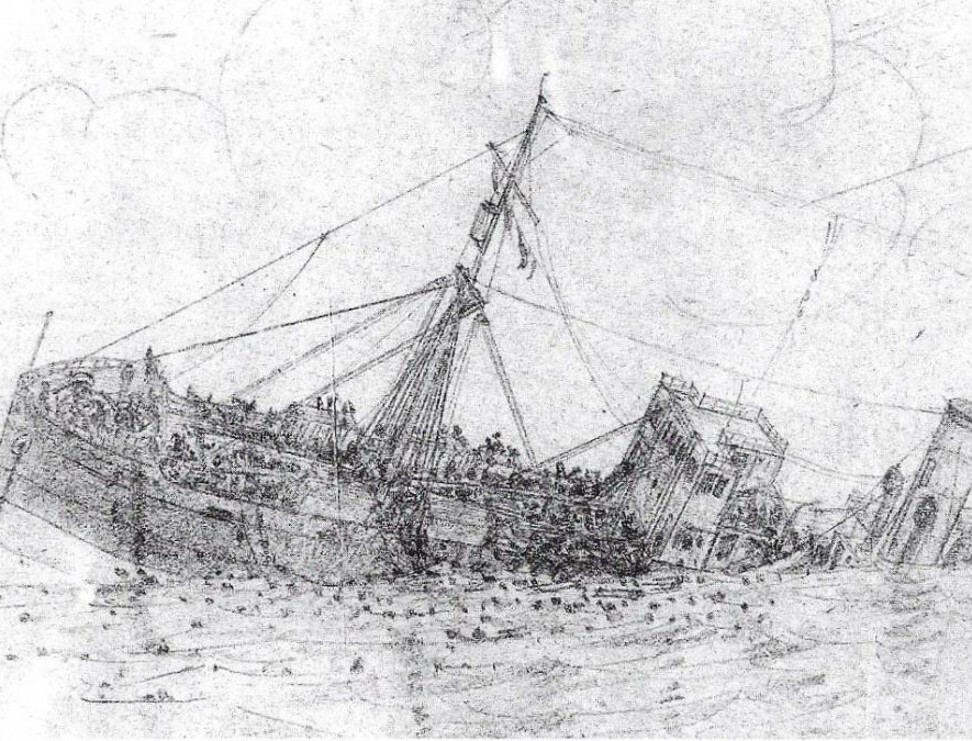

Morley had a round, open face and a friendly demeanour, but he was frank. If they made a movie about the Lisbon Maru, he quipped, he could be played by Tom Cruise. The film would have to tell it like it was, however – how the captives sat crowded on the floor of the hold as the water flooded in, and how their excrement rose and floated around them.

Like many veterans, Morley did not speak for decades about his wartime experiences. His daughter, Denise Wynne, says she was stunned to hear about them for the first time a few years ago.

The Danes who defied their king to enlist in Hong Kong’s defence

“I never realised what he had been through and how hard it must have been. He was a true survivor,” she says from her home near Stroud, in the English county of Gloucestershire, where Morley lived with her for the last 15 years of his life.

At the end of the war, former prisoners in Hong Kong returned to their home countries, got jobs, married. Life moved on. Then about 20 years ago, Morley wrote to Hong Kong war historian and author, Tony Banham.

“He put a question on a website about his friend Paul Connolly, who was executed by the Japanese, and I replied to him and we just started corresponding from there and later meeting,” Banham says.

Banham has written a number of books on wartime Hong Kong, including The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain’s Forgotten Wartime Tragedy, in which he details the journey of the freighter loaded with prisoners, including Morley, from the Sham Shui Po camp on Hong Kong’s Kowloon Peninsula.

Born in London in October 1919, Morley initially worked for Philips Radio, but had a hankering to travel, says Banham, so he joined the army. He was posted to the Second Battalion of the Royal Scots regiment in Lahore, India, as a bandsman in 1938 before relocating to British Hong Kong.

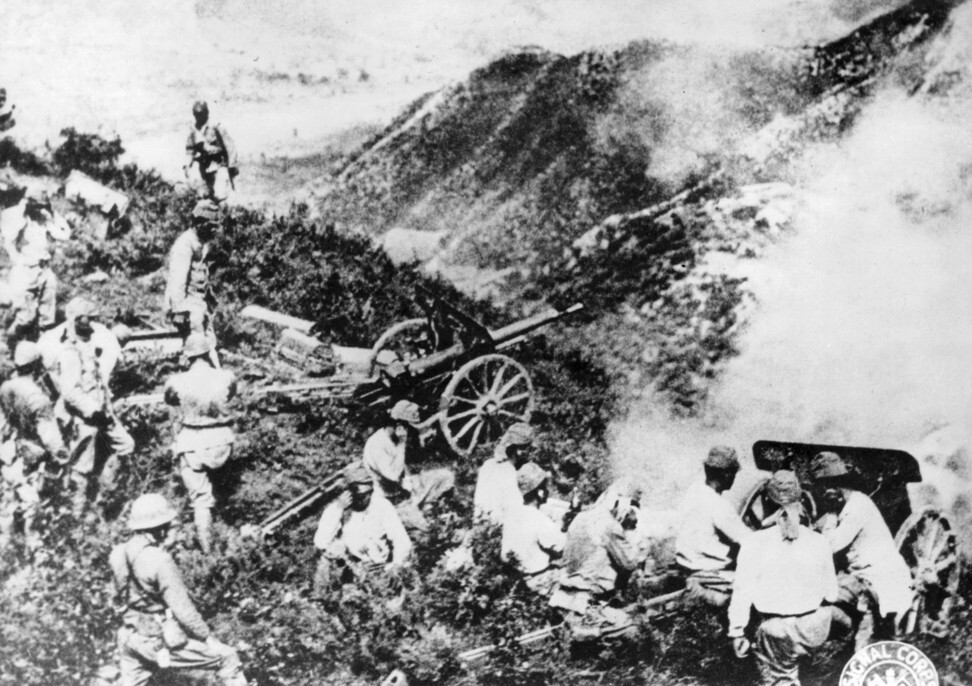

When the Japanese military invaded the territory on December 8, 1941, Morley was initially at the defensive “Gin Drinker’s Line” in the rural New Territories, but the Japanese swept through in a matter of hours. As local forces withdrew to Hong Kong Island, he was involved in ferocious fighting on Mount Nicholson, overlooking the key artery of Wong Nai Chung Gap.

“It was dark as we made a counter-attack under Captain [Douglas] Ford, but we just couldn’t do anything,” he told this writer in 2006. “They threw everything they had at us – grenades, sniper bullets. We had to retire.”

His group held their positions for the next two days. “We’d been going since December 8. We were tired, hungry, feeling awful. I can’t remember whether we slept or not. I think we just got five minutes of shut-eye where we could,” he said. “We were being sniped and everything. There was a Japanese spotter plane overhead letting them know where we were.”

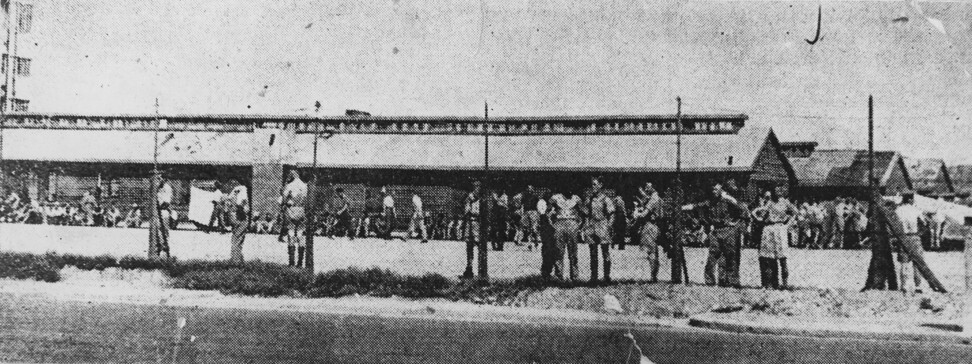

When Hong Kong surrendered on December 25, 1941, the surviving forces were rounded up and later marched to the Sham Shui Po camp.

In the initial months, many perished from diphtheria and other diseases, and Morley and Connolly spoke of escaping. So it came as a shock to Morley when his friend tried to escape with others and got caught. Connolly was executed – a tragedy that would haunt Morley.

The Japanese soldiers were taken off the ship during the night and transferred to patrol boats. They left us to drown

Although he had approached Banham, Morley resented him initially, the historian says, because it brought back memories of tragedy and trauma. But it was also what led to his trips to Japan, which seems to have helped him come to terms with his past.

“I lost my youth here,” he said in November 2006, while laying a wreath at the Cenotaph in Hong Kong’s Central district. “It wasn’t until I went home that I started reliving my youth again.”

On September 25, 1942, Morley had left the Sham Shui Po camp with 1,815 other British and Canadian prisoners to board the Lisbon Maru, one of a number of vessels that transported men to Japan to work in the dockyards and elsewhere as slave labour.

The men were crowded into three squalid holds designed for goods. Initially, says Banham, they were allowed to go on deck and get air, and also visit the rudimentary toilet.

There was nothing on the freighter to indicate it was carrying prisoners. Then, on October 1, off the coast of China’s eastern Zhejiang province, the American SS214 USS Grouper submarine, which had been tracking the vessel, fired six torpedoes; one hit its target.

As the hours passed, water poured into the freighter. Many of the men would escape on deck or jump into the water, and many were shot or drowned, according to Banham. Hundreds went down with the ship. In an amazing feat of courage, Chinese fishermen off Zhejiang’s Zhoushan islands did hundreds of sorties, picking up men and ferrying them back to the islands despite the presence of the Japanese military.

“The Japanese soldiers were taken off the ship during the night and transferred to patrol boats [with a few left on board]. They left us to drown,” the late Jack Etiemble, a trumpeter in the 8th Coast Regiment at Stanley Fort, told me in 2005, aged 81.

Men from the hold in which Etiemble had been placed began to climb an iron ladder out to the deck. After Etiemble climbed up, the ladder gave way. “No other POWs could get out, and down in the hold was an Irish gunner. And I heard this gunner shout: ‘We can’t get out, let’s give them a song.’ So they sang It’s a Long Way to Tipperary and that was the end of my regiment.”

Some 828 men perished in the Lisbon Maru tragedy, but a further 200 would die from exposure and exhaustion in the days that followed. Of the men saved by the fishermen, three escaped, while the rest surrendered to the Japanese.

Morley spent the next almost three years in slave labour at Kobe House POW Camp in Osaka, and survived yet again when American B29 bombers conducted incendiary raids towards the end of the war.

“There were fires all the time,” says Banham, describing Morley’s account to him. But, he says, Morley by then had been through so much it was just one more thing to deal with. His was an extraordinary life of surviving so many acts of violence that maimed or killed his friends.

When Morley finally arrived home in Britain at the end of 1945, the nation had moved on, he told me, and the role of soldiers fighting in East Asia had been forgotten. “When we got back, they did not want to know us,” he said.

He married Phyllis Grace, whom he met while working at a hospital, and they had a daughter, Denise. But his wife died of cancer at the age of 30, when Denise was three years old. He married his second wife, Eva Starkey, in 1952 and had a long marriage before his wife predeceased him.

He let me in on a secret when I met him. “If you want to stay young, Annemarie,” he said, “then the best thing to do is hang around with young people.”

Those included his two grandchildren, four great-grandchildren and a great-great-granddaughter. He loved to walk in Snowdonia and the Lake District, says Denise. His hobbies included tennis, gardening and riding his Vespa scooter.

Morley embraced modern Japan and the friendships he made among the younger generation, but he never forgave his captors nor forgot what happened. He still mourned his fallen comrades.

“We were hostages to fortune,” he said. “You think of all those that you knew. They were only kids.”