Damien Hirst encrusted a skull with diamonds, and Takashi Murakami turned out canvases with cartoon versions of skulls. But when Zhang Huan addresses similar iconography, he creates paintings in a style all their own. Sitting in his Shanghai studio one day recently amid dozens of Tibetan death masks, he was busy preparing for the recent opening of "Poppy Fields", an exhibition of new works at the Pace Gallery in New York.

"Poppy Fields" is a fresh direction for an artist whose studio is much like a factory, with more than 100 assistants churning out copper sculptures of Buddhas, paintings made of ash collected at temples, doors carved with scenes from the Cultural Revolution, stainless steel pandas, stuffed cows and horses and, on one occasion, a version of a Handel opera. His notion is that he can produce anything he imagines without regard for consistency.

"Unlike Western masters, who will stick with one style their entire life until they reach maturity, I am in a constant state of transformation," Zhang says. "I am constantly abandoning old things for new ones, but there is always a thread behind these changes, and that is my DNA."

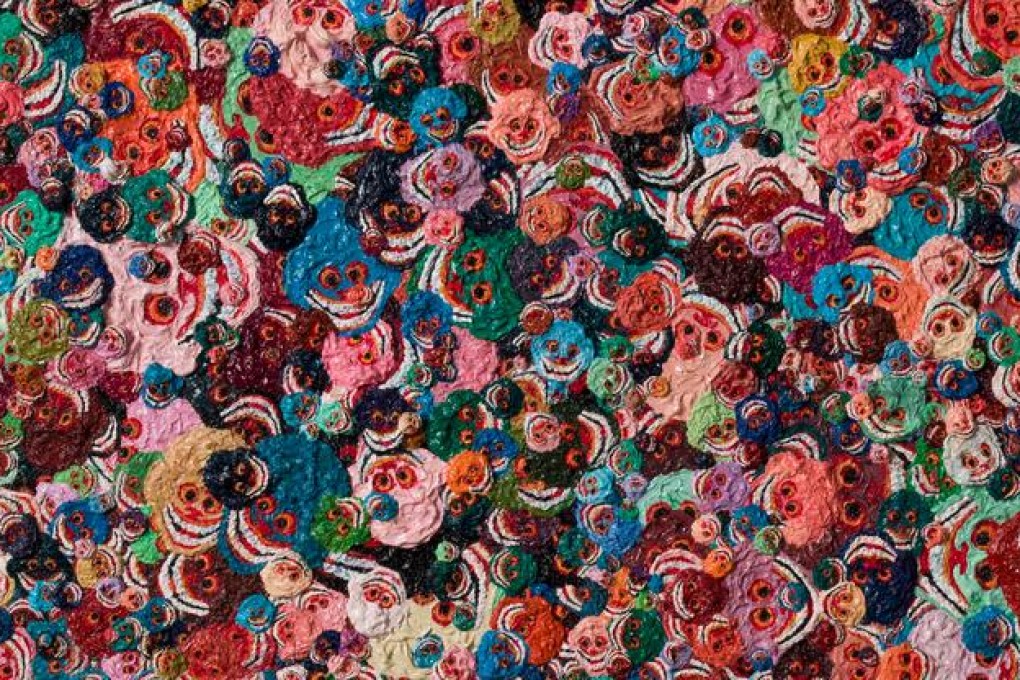

In the new paintings, the canvas surface is covered with hundreds of skulls modelled after Tibetan masks that look like grinning faces with bulging eyes and Cheshire cat smiles. From a distance, the canvases blur into misty fields of colour, in white, pink and blue in one instance and black, red and gold in another. Yet up close, you can see each face in the crowd, as if you're zooming into a packed stadium from outer space.

"The paintings represent the hallucination of happiness and the hallucination of fear and loneliness in this life as well as the hallucination of happiness in the next life," Zhang says. Asked about his bright hues, he says:"If there's no colour in your hallucination, it won't be heaven. It would be hell."

Buddhism and death rituals have been abiding subjects for Zhang, who was ordained as a Buddhist monk eight years ago. During the anti-religious oppression of the Cultural Revolution, Zhang, born in 1965, remembers watching his grandmother go to the temple and burn incense before a statue of a Buddha. As an adult, he went regularly to temples; even after moving to New York in 1998, he studied every weekend with a monk in Queens, and later donated statues to the Chuang Yen Monastery, designed by I.M. Pei, in New York.