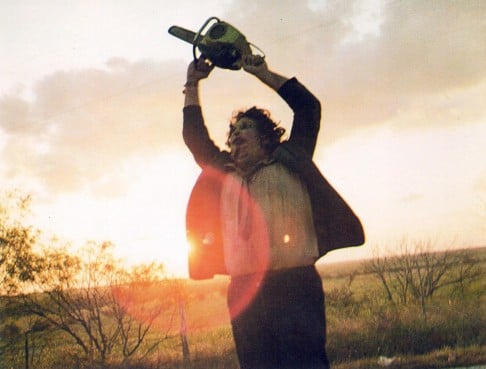

Horror film genre's defining moment

Forty years after its release, horror genre-defining film The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is still terrifying

Forty years ago this month, was released in cinemas. Yet even as it enters its fifth decade, Tobe Hooper's horror film remains a master class in terror, having lost little of its power to shock, fascinate and repulse - often at the same time - since it appeared in 1974.

Enthusiastically introducing a screening of a restored version of the movie at the Cannes Film Festival this year, Denmark-born Nicolas Winding Refn ( ; ) said seeing at the age of 14 made him want to be a director.

While not everyone's life is changed by watching the film, few forget its disturbing imagery or the creeping sense of dread it produces.

"Most horror movies, you walk out and you don't take anything home with you," says Gunnar Hansen, who plays Leatherface, the masked, chain saw-wielding killer. "This has the opposite effect. You walk out carrying a lot of baggage that it piled on top of you."

Yet despite the promise of grisly carnage in its title (others considered included and ), there is hardly any blood in the cult movie. Even so, people often swear it is the most gruesome film they have ever seen.

"It's subliminal," Marilyn Burns, who played tortured heroine Sally Hardesty, told me. "You imagine you see so much more than there is, because of the texture of the film." (Burns died in August, aged 65.)

Hansen suggests operates on a deeper psychological level than films that rely on the "boo factor" and graphic gore. Horror, as a genre, has its roots in the gothic tradition, the actor-poet says, "which really has to do with the discovery of the unconscious and the dark side of humanity. taps into the original motivation for gothic. Every time you watch it, you are reminded of this deeply dark and disturbing and uncomfortable and nasty part of human nature. That sense of discomfort is why the film keeps its power."

It was made at a time when American cinema was starting to reflect the social and political disturbances rocking the country. Charles Manson had turned the hippie dream into a blood-drenched nightmare, the Vietnam war was raging, and president Richard Nixon was embroiled in the Watergate scandal. Cinematic offerings such as George Romero's and Wes Craven's brought horror out of the realm of the supernatural and into the everyday.

Hooper's film continued the trend by locating the dread right at the heart of the American family. With Grandpa mouldering in the attic and the cross-dressing Leatherface acting as housewife, Hooper and screenwriter Kim Henkel's clan of unemployed slaughterhouse workers ironically upheld the values of family unity.

Their collision with young urbanites driving through Texas in a van creates a clash that chimes with today's age of Occupy. Hansen remembers someone at a post-screening Q&A suggesting that it's like the "yuppie, privileged, college class meets white trash". They have a point, he says.

"Here are the privileged few with no sense of what life's about. They have mummy and daddy's gas credit card, and they've never had to struggle for anything," the actor says.

"Now, suddenly, they are faced with the hard reality of life, which is the unemployed, blue-collar, uneducated person who's just trying to survive, and has decided to do this by eating the rich.

"I don't think that's what any of us was thinking but it's consistent with what you are seeing. It's a legitimate view of the movie."

Mostly, the people behind the film just wanted to terrify the audience. And they went to extremes to achieve it. Shooting in Texas at the height of summer, in 43-degree Celsius heat, the actors threw themselves into their roles to the point of exhaustion. Despite the limited budget, Hooper demanded take after take - and Burns gave him all she had. "I tried to give him my best performance every time so that I couldn't have my worst performance on film," she recalled. "And if I gave him consistently high energy, that's what he would capture."

Every time you watch it, you are reminded of this deeply dark and disturbing and uncomfortable and nasty part of human nature

Her hair was singed by gunpowder. She hurt her ankle, received a black eye after being hit repeatedly with a broom, was knocked unconscious, and had a dirty rag stuffed in her mouth as a gag. While filming the infamous dining-table scene, Hansen removed the safety tape from a knife and sliced Burns' finger for real.

"Marilyn was getting injured so she was hurting a lot and would rightly complain about it. So, when she screams, they're thinking, 'Good job'. She was getting thrown to the ground. She was tied up," he recalls. "Nobody was being very gentle about anything with her. There was never a reason for them to think that this was anything but acting and, sort of, a minor injury."

He lost perspective and crossed a line in his mind, Hansen admits. When someone said, "Kill her", he thought, "Okay". He recalls: "I was so tired and so trying to get done with this. In the next couple of days I thought, 'This is a little disturbing.' I had always felt that I didn't have to be [Leatherface], that all the time we were doing filming, there was a separate voice that was watching what I was doing … So I did not like the fact that this moment had happened," he says.

Still, the results speak for themselves. Four decades on, is regarded as a classic - it has a place in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. No one involved could have predicted the film's long-lasting cultural impact.

Burns, though, always had faith that it would at least play in theatres. "I thought, 'We went through too much. It has to make it.' It would have been so cruel if, after all that hell we went through, it didn't get anybody's attention."