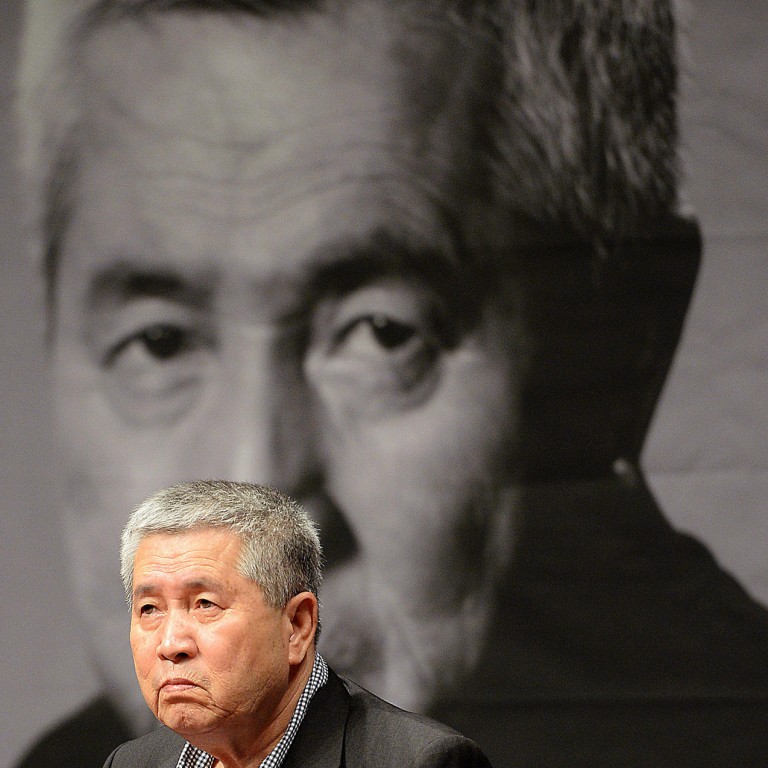

Keeper of the flame

Revered director Im Kwon-taek's works reflect on fading Korean values

Im Kwon-taek appears to be having the time of his life. While most men of 78 seldom have to concern themselves with more than the contents of their kitchens and perhaps a daily stroll, you get the feeling Im still wakes up each morning ready, willing and able to wrestle with the muse.

"Life without film, life without creating film, is something I cannot even consider," says the venerable director, whose debut work, , was released in 1962. "It is what drives me and what has always driven me."

At the Busan International Film Festival last month, he screened the latest fruits of his labours. Like many of Im's films in a career that spans more than five decades, his 102nd film reaches deep into the Korean psyche.

In , veteran actor Ahn Sung-ki plays a businessman whose wife (Kim Ho-jung) has a terminal illness and whose attention is turned by a much younger and apparently attentive woman in his office (Kim Qyu-ri). Taken from a popular Korean short story - whose title means both "make-up/cosmetics" and "cremation" - it is a relatively simple affair, on the surface at least, but Im has helped his actors reach into their characters' souls. It is simply done, rarely sentimental, but often quite staggering. The director had never before tried to turn a piece of literature into a film and found the process challenging.

"This film wasn't an easy task," says Im. "It was a challenge to find a visual language for the author [Kim Hoon's] words. It is a more modern story in a way, but these themes are common. I was able to take the book but used the experiences I have accumulated in almost 80 years of life into the film. As you get older you think about these issues more. I want to explore them and I want challenges when I make films."

Im can be found each year at the Busan festival, either because he's screening a fil, having his work featured as part of retrospectives, or simply because he loves film, taking his place among the audience during screenings or walking around the Busan Cinema Centre which hosts the event, stopping to chat with friends and fans.

The respect the septuagenarian filmmaker is given, and even the awe in which he is held, is made apparent after our screening of , when a young film student quite visibly starts shaking as she offers her respects - and a question - to the director, and then thanks him profusely for being "my life's inspiration".

When the session ends, Im calls the students and festival volunteers in the room together so they can all pose for a photo. The director says he has tried to never lose sight of the fact that he, too, was once a student.

"Artists need to have the confidence to face the creative process; sometimes you want to just run away," he says. "In the end, however, I stuck with filmmaking - not that I had been talented enough to try anything else - because I simply love movies."

Outside South Korea, and away from the festival circuit, Im's name is not as widely recognised as it should be and that's perhaps because he has focused for so long on quiet films about the human condition, often linked to parts of his culture he thinks the country may be losing.

In - his 2002 masterpiece which saw him become the first Korean to be named best director at Cannes - the story is framed around the life of Korean artist Jang Seung-up, but is also about a man's (and South Korea's) search for identity. In (1993) and (2000), the characters' day jobs involve music but their purpose is also to help the audience ponder the fate of lost traditions. These are richly textured films which have drawn often career-defining turns from his cast, something Ahn, who has made seven films now with Im, puts down to the director's "patience and his skill as a storyteller".

I want people to reflect on how times are changing, the things we are in danger of losing, and how important these things are as we look to our future

"He takes the time to work very closely with you, explaining what he wants from the character and from the film," Ahn says.

"That's why all Korean actors want to work with him. He chooses topics that we can all relate to, and gives us the freedom to explore the character and the filmmaking process," the star says.

Initially, Im was part of a state-sponsored film industry that saw him piecing together around eight films a year, restricted by South Korea's former military-led government which heavily censored content and kept productions constrained by strict formulas. Sacrifice for the greater good was a common theme in Im's films from the early 1960s all the way up to the 1980s, when change came.

Before a retrospective of his films at Busan last year, Im talked about how he found freedom through film. "I am not very proud of the first 50 or so films I made. The military government of the time had strict ideas for us, but when things changed I was able to finally truly express myself and my love for Korean culture and stories," he says.

"I want people to reflect on how times are changing, the things we are in danger of losing, and how important these things are as we look to our future. These are the things that interest me and I cannot think of a time when I am not making films."

Even with 102 films in the can, Im continues looking towards the next challenge, and to how he can further reveal to his audiences the things he has learned about life.

"Part of getting older is that you reflect on what you have learned," the filmmaker says.

"So I want to keep looking at these things, talking about life and the things that affect us all. Through the long years of my career as a director, I have taken comfort from the fact that my films seem to touch people and seem to have a power, and I promise I will keep making them for as long as I possibly can."