High-end art boom brings few rewards for the big auction houses

High-end art sales are buoyant but auction houses don't see the rewards

The recently released quarterly results for the world's two largest auction houses trumpeted an art market in perpetual boom. Christie's, the biggest clearing house for ultra-expensive pictures and baubles, posted US$8.4 billion in sales, up 17 per cent year on year. Sotheby's, its arch rival (and former collaborator in a price-fixing scandal), saw its sales rise by a similar percentage, to US$6 billion. Just like in the mega-galleries of New York and London, or at the art fairs in Miami and Hong Kong, the appetite to buy in the world's high-end salerooms grows ever more ravenous.

Yet inside the corporate offices of Sotheby's and Christie's, the mood has been much grimmer. For a start, both houses have had a shake-up in senior management: Sotheby's chief executive William Ruprecht announced he would step down after 30 years at the company in November, while Steven Murphy, chief executive with Christie's, announced he would resign the following month and will be replaced by Patricia Barbizet, a longtime loyalist of majority owner and French billionaire François Pinault.

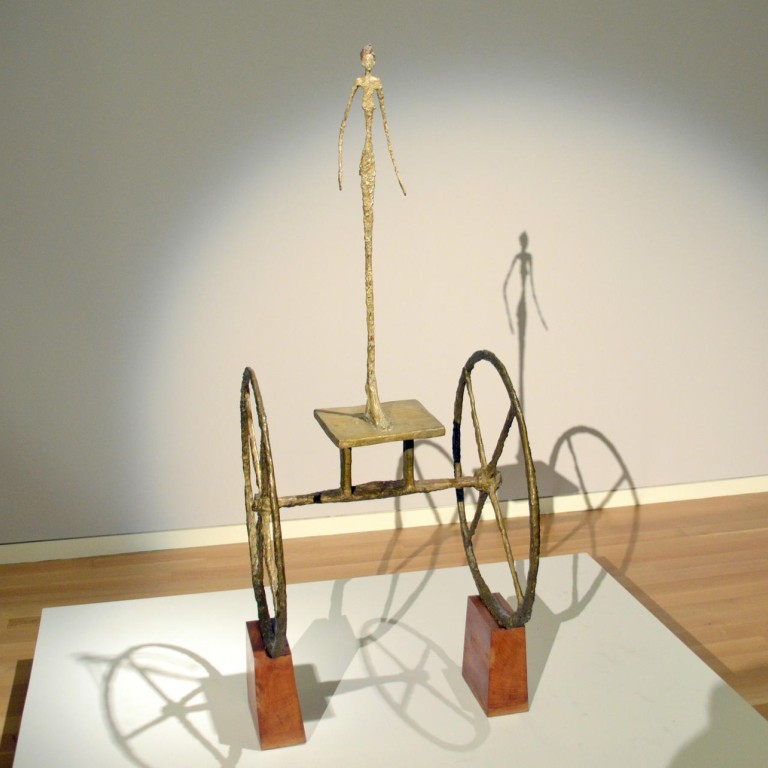

You might think that the ever-increasing prices for contemporary art - US$142 million for a Francis Bacon triptych, US$101 million for a sculpture by Alberto Giacometti, or US$70 million for a Cy Twombly painting of loop-de-loops - would trickle down into the auction houses' coffers. In fact, Sotheby's (a listed public company) and Christie's are only moderately profitable. While Christie's does not disclose its profits, at Sotheby's profits fell 15 per cent in the first half of 2014, despite increasing sales. The accelerating concentration of wealth in the hands of the ultra-rich, and the brutal competition the two houses have waged to win their business, have left Christie's and Sotheby's far less than flush.

The accelerating concentration of wealth in the hands of the ultra-rich, and the brutal competition the two houses have waged to win their business, have left Christie’s and Sotheby’s far less than flush

Take that Giacometti. At US$101 million, the Swiss artist's (1950) was by far the priciest lot at Sotheby's impressionist and modern art sale of November 2014. Yet it failed to break the record for Giacometti at auction - and in the saleroom on York Avenue, the action was noticeably thin.

Bidding started at US$80 million, and increased to US$82 million, US$84 million - but these were not actual bids. They were so-called "chandelier bids," called out by the auctioneer himself in a theatrical attempt to get things moving. It's a practice that's entirely legal, and common. In 2013, reported that for the past two decades lawmakers have tried to outlaw it, but without success.

Only at US$90 million did a bidder, Steven Cohen (who was represented by a Christie's agent), place a bid for the Giacometti. And that was that: down came the gavel, and the one-bidder auction was over. The remainder of the final price of US$101 million constitutes the buyer's premium, that is, an additional charge paid to the house.

Then begin the discounts. At the lower end of the market, consignors to Christie's and Sotheby's pay a 10 per cent and 15 per cent fee to sell their work - but to win bigger consignments, the houses often waive the fee entirely. Beyond that, the houses sometimes offer consignors a percentage of the hefty buyer's premium (known as "enhanced hammer"), thus allowing certain ultra-wealthy collectors to take home more than 100 per cent of the sale price. Daniel Loeb, an activist board member who has been pressuring Sotheby's to grow more profitable, specifically cited that practice when he lashed out at the auction house and called on Ruprecht to step down.

The houses also have gargantuan marketing costs. The Giacometti was splashed across the pages of newspapers and magazines ahead of the sale, and promoted with a lavish catalogue. It would have been presented to prospective bidders in the best possible light; the auction houses are known to ship works to collectors' houses before the sale to let them "live with the art" for an hour or two. At Christie's, premium clients from China were flown to New York and wined and dined.

Finally, Sotheby's offered the seller of the Giacometti a guaranteed payment, regardless of the final price of the work at auction. The houses refuse to disclose the values of these guarantees, but the more prestigious the lot, the more generous the house will be. To secure the Giacometti for auction, Sotheby's auctioneers would have ensured the seller a payment almost as high, if not higher, than the price Cohen paid. Publicly, Sotheby's had announced before the sale that the Giacometti would sell for "in excess of US$100 million". The guarantee would not have been for much less.

All of this raises the very real possibility that Sotheby's lost money selling a US$101 million sculpture. The real margins are to be made on the wine and the knick knacks at the bottom of the market. At the very top, the air is much thinner.

One of the principal issues at play in the upheaval at the auction houses concerns the use of guarantees - baseline payments to consignors made whether or not a lot sells. Most objects at auction, from watches to wine to your grandmother's china, are placed on the block with no guarantees: if the lot fails to sell, that's your bad luck. But the scarcity of first-rate contemporary art gives ultra-high-net-worth sellers leverage to avert risk and maximise profit. Playing one house against the other, they began in the past decade to lock in guaranteed million-dollar payments.

At first, Christie's and Sotheby's financed these guarantees themselves. But in late 2008, in the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the near-collapse of the entire global financial system, the two houses presided over painfully weak sales of contemporary art - and were forced to pay out tens of millions in guarantees to consignors. Since then, the houses have pioneered the so-called "third-party guarantee", a little-understood but critically important shift in art finance. These third-party guarantees decreased risk for the houses, but cut into their profits and may also have had market-distorting effects.

Just as with a regular guarantee, with a third-party guarantee consignors receive an assured payment regardless of a work's fate at auction. But now, that payment is staked not by the house but by an outside investor. If the work's price fails to exceed the guarantee, then the third-party guarantor acquires the work. If bidding is more robust, then the guarantor receives a financing fee.

The guarantor is still permitted to bid on the art they have guaranteed, which raises sticky questions about fairness and transparency. He or she may also receive undisclosed information about the artwork and its potential market, which is common practice and entirely legal in the unregulated art world - but would get you sent to prison in the world of stocks and bonds.

Nevertheless, in 2015 Sotheby's and Christie's have returned to guaranteeing artworks on their own accounts ahead of modern and contemporary sales in London. This lets the houses take the upside if things go well. It also leaves them holding the baby if the market crashes. The boom in the contemporary art market has taken place at a moment of global economic stagnation, and the rise in art prices parallels the increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of the super-rich. If this unequal distribution of wealth endures, then the art market may continue to boom for many years to come.

But that does not necessarily mean that Christie's and Sotheby's will reap the benefits. Under new leadership, the auction houses may reorient their businesses to favour more profitable enterprises, such as less expensive art, collectibles, and real estate. But for the high-priced contemporary art that the media love to hype, they will probably continue to serve as just another set of underpaid servants to the international super-rich.