Where do artists draw the line between copying and theft?

After a jury determined Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams copied parts of Marvin Gaye's in their hit - and awarded Gaye's family US$7.4 million - the music industry erupted with criticism and praise. But borrowing, appropriating and stealing are as old as art itself.

Where do you draw the line, especially in visual art, classical music and theatre? There's no history of art without borrowing, appropriation and, in some cases, outright theft. Certainly the past century is inconceivable without found objects - a urinal signed by Marcel Duchamp, a bicycle seat and handlebars turned into an animal head by Pablo Picasso, and almost everything Jeff Koons has ever done.

The 20th century began with collages made with images torn from newspapers and was dominated by pop art, which meticulously reproduced the products of advertising and commercial design. Long aeons of art have been devoted to small variations on familiar and beloved formulas - so familiar that we have named them the annunciation, deposition, sacred conversation, assumption. The Romans copied from the Greeks, and thank goodness they did: much of what happened in the age of Socrates, Plato and Menander is known to us only through Roman facsimiles.

But there's also been a history of forgery, especially as art became a valuable commodity in the 19th century. Forgers have even laid claim to legitimate status for their work, and used the same arguments circling in conceptual art circles for justification. If Elaine Sturtevant, the subject of a recent retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, can make nearly perfect copies of pop art and call it new, why should forgery be seen as illegitimate?

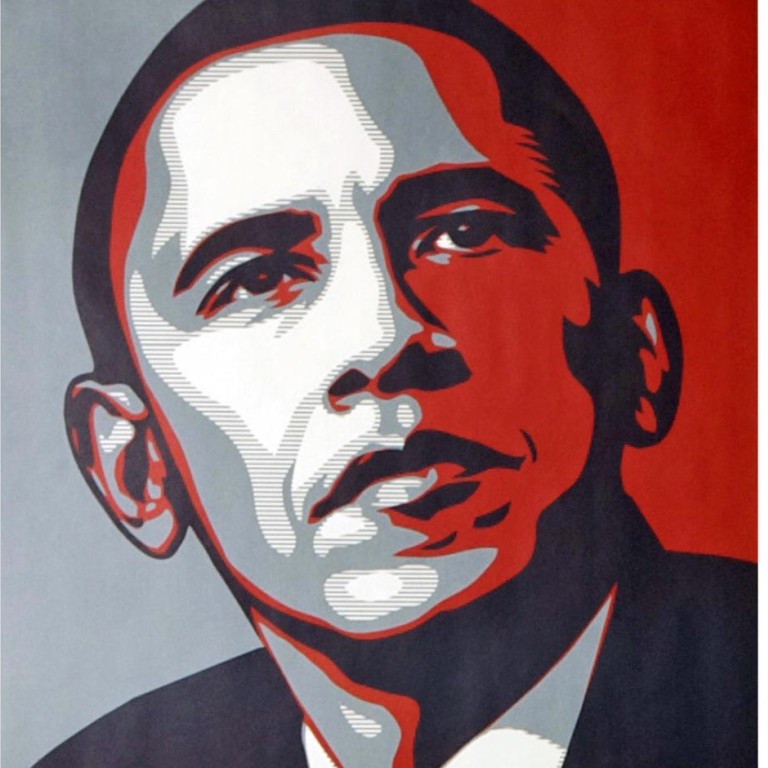

Legally, the artist must add something - an idea, a nuance, a criticism - to the work they appropriate; it mustn't be done simply to deceive; and no one should prosper by borrowing if it comes at the expense of another artist. Shepard Fairey based his famous Obama poster on an image by an Associated Press photographer. He claimed he didn't and destroyed evidence, but when the law got involved, Fairey was sentenced to two years of probation, community service and fined US$25,000.

In the art world, though, it's in bad taste to get too worked up about appropriation. Because without it, there's almost no art to talk about.

"Good artists borrow," Russian composer Igor Stravinsky is supposed to have said. "Great ones steal."

Verdi obviously had heard Rossini's a time or two before writing ; Leoncavallo meant it as an homage to Verdi when he quoted a line of at the end of the prologue in .

Sometimes such "borrowings" are to make a point, as when Shostakovich took a line from Lehar's and included it in the tune that he repeated over and over to denote the incoming German forces in his Seventh Symphony. Bartok heard this on the radio, found it trite, and cited the passage mockingly in his own . Another story goes that when someone asked Brahms about the obvious parallels between the final movement of his First Symphony and the theme in Beethoven's Ninth, Brahms responded: "Any ass can hear that!" No damages were paid.

Bruce Norris' 2011 Pulitzer Prize-winning didn't steal from Lorraine Hansberry's 1959 (which is still copyrighted) because merely started with that drama's situation then created a whole new play moving years into the future.

Unlike Hollywood screenwriters who get paid but lose copyright control to the studios, playwrights - usually poorly paid - at least retain copyright.

If a playwright were to try a freewheeling, blurry-lined adaptation of, say, Tony Kushner's early 1990s or Ntzoke Shange's 1975 without first licensing the rights, odds are pretty good that would be stealing.