Chinese artist Cao Fei defends film shot in Hong Kong arts centre, a former prison, that looks like promo video

Prison Architect, a film about turning an art centre into a prison – the reverse of what happened at Tai Kwun in Hong Kong, where it was filmed – is a continuation of her works exploring the meaning of prison, artist says

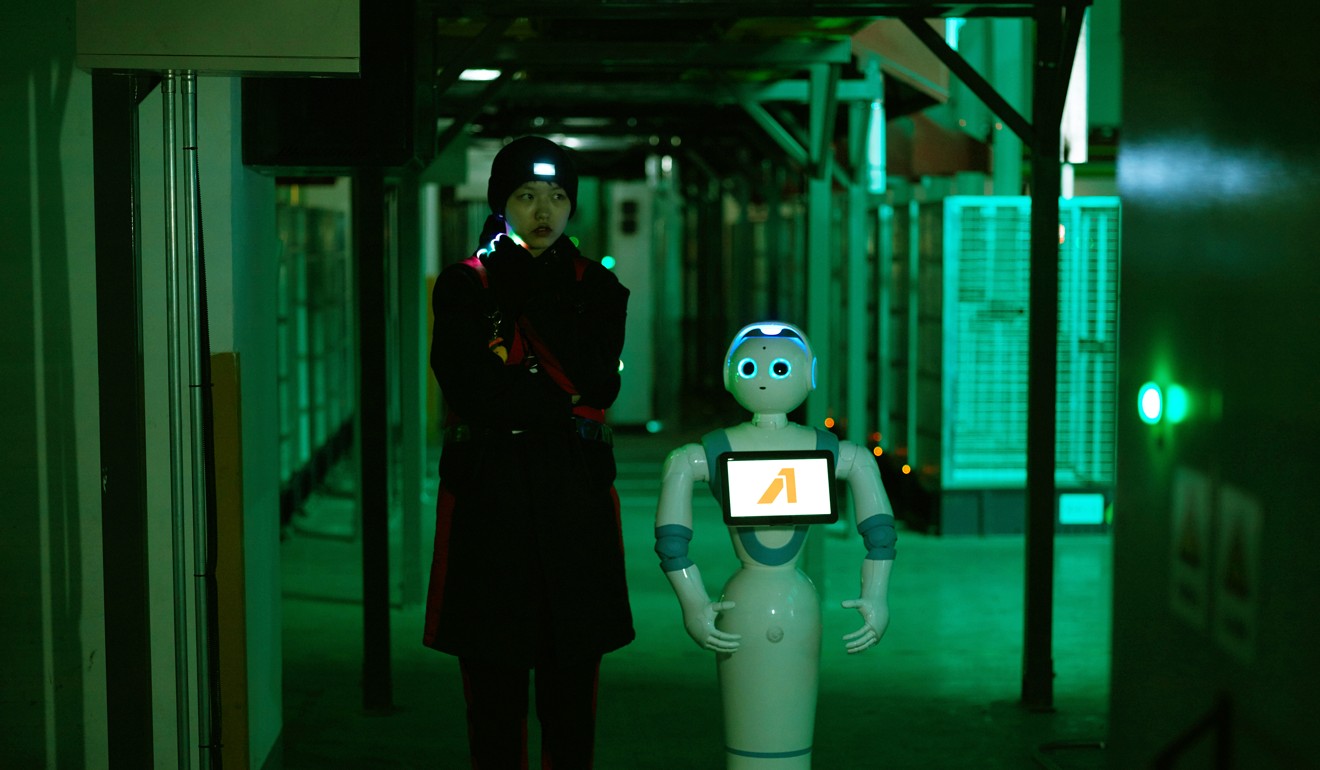

Viewers of Chinese artist Cao Fei’s film Prison Architect sit on unpadded prison bunk beds to watch it at Hong Kong’s former Central Police Station and Victoria Prison, now called Tai Kwun, where most of the shooting took place.

That’s not the only discomfort audiences experience. The 40-year-old artist, so adept at capturing the malaise of Chinese society, has made a film that feels like a promotional video, even if it isn’t meant to be.

Bad English at Tai Kwun reflects Hong Kong’s falling standards

In the hour-long film, actress Valerie Chow plays a cosmopolitan architect charged with turning an art centre into a prison – the reverse of the Tai Kwun rejuvenation – and Hong Kong artist Kwan Sheung-chi plays a local poet locked up by the colonial police during the pro-Communist 1968 riots.

The two characters never address each other directly but we hear their voices as if they are in dialogue across time. Chow struggles with the ethics of designing a prison while she walks through Tai Kwun, which gives the opportunity for many lingering shots of the beautifully restored architecture. Kwan, looking doleful throughout, wallows in his cell with no hope of ever leaving, and writes poetry in an illicit notebook given to him by a kind policeman.

There are bursts of exuberance, such as when the officer delivers a thrilling tap dance routine on top of the trap door connecting the cells to the courtroom, and when the prisoners are all let out in the final scenes and they sit in the parade ground gnawing on the fruit of the old mango tree there. And the conceit of comparing a prison and an art centre is an interesting one. Both places have specific codes of behaviour and both are strictly hierarchical when it comes to determining the actions of others: the prison wardens and museum curators hold the power.

Throughout the film, Cao pays homage to the cultural influences she came across as the intellectually curious daughter of two professors at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts: poems by Huang Canran, who worked for years in Hong Kong as a translator; the soulful singing of the blind dishui nanyin genre, a tradition of Guangdong province; and Hong Kong films.

Zeng Fanzhi’s first Hauser & Wirth solo show happening this autumn

It is all done in the best art house tradition – Cao is a movie junkie who cites Guangdong’s Pearl Studio, Federico Fellini and Shuji Terayama as influences. But there are scenes that seem to be a crass acknowledgement of who is paying for the film.

There is the sound of horses galloping that is extraneous to Tai Kwun’s history or the storyline. Cao says that was a “random” choice by the sound team rather than a nod to the Hong Kong Jockey Club, whose charitable arm is behind the compound’s revitalisation.

The breezy rendition of Auld Lang Syne accompanying the sweeping aerial view of the restored Tai Kwun, and the applause that Chow’s speech on architecture receives from the freed prisoners, simply feel out of character for Cao.

The film was commissioned by Tai Kwun, and Tobias Berger, its head of art, says it is one of the “most ambitious projects any single artist has attempted in Hong Kong”. It is also the focus of Cao’s biggest solo exhibition in an Asian institution, as a number of older works and new installations are also on display.

Cao says Prison Architect is a new experiment because of the scale of its production. It is the first time she has worked with mainstream film professionals, such as Chow and the award-winning cinematographer Kwan Pun-leung, both from Hong Kong. A crew of more than 30 people helped her.

She argues against the idea that the film is anything but an independent work of art. “This is a work that continues naturally from the other works I did where I explored the concept of a prison, and the blurred lines between liberty and confinement,” she says.

For example, in iMirror (2007), Hug Yue finds freedom in the virtual world from his past as a bank robber, but is aware that audiences are watching him.

Other films have contained ideas of a jail break of sorts, though liberation rarely comes in such rip-roaring form as Chow Yun-fat’s desperate leap into freedom in the clip from Prison On Fire 2 (1991) that Cao uses in her new work.

In Cao’s Whose Utopia? (2006), the assembly line workers’ escape is their dream of doing a job that is completely different; in Cosplayers (2004), the young and the bored rise above the mundane by donning elaborate costumes and getting into anime characters.

What she has added in Prison Architect is the idea of a prison as refuge, and as a place of inclusiveness.

The title of the entire exhibition is “A Hollow in a World Too Full” and features, as well as iMirror, LA Town (2014), her dystopian adaptation of French writer Marguerite Duras’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour, and Coming Soon, a performance first seen in Shanghai’s Long Museum in 2015. Two people move back and forth across a room on two swings and use their feet to make anticipatory drum rolls on the drums and cymbals fixed sideways on the walls, a rather depressing parody of the pursuit of happiness.

Cao’s life has become very full since she returned to making art full-time in 2013, after taking time off to give birth to two children and to become properly grounded in Beijing, her home since 2006. In 2016, she had a solo retrospective at New York’s MoMA PS1. Later this year, she has a retrospective at Dusseldorf’s K21 Standehaus.

While she continues to earn international praise, a major show in mainland China has yet to happen (though, in 2020, an expanded version of “A Hollow in a World Too Full” will be held at UCCA in Beijing, the contemporary arts centre that is presenting the Hong Kong show).

Her popularity abroad has much to do with her clear-eyed, subversive and affectionate portrayals of contemporary Chinese society. In China, she is still considered too young to have a major retrospective, she says, and statistically, female artists have to wait longer to earn such a privilege.

“The work that I do also tends to reflect on ordinary people’s lives. Perhaps people in China feel that they don’t need to see the films because they are living them. Perhaps a distance of five to 10 years is required before they can appreciate them more objectively,” she says.

Maybe that is the problem with Prison Architect. In five or 10 years’ time, perhaps its reminders of the fanfare behind Tai Kwun’s opening will have become a distant memory and therefore less jarring.