Hong Kong artist Hon Chi-fun, who blended traditional East with modern West, dies aged 96

- Hon, born in 1922, moved among art genres such as acrylic paintings, Taoism inspired screen prints, multimedia works and writing poetry

- The self-taught painter worked until the age of 94, even after having a stroke in 2000

“The enemy is at the gates. Death, just like the Japanese army in the war, is coming to get me,” he said ahead of his solo exhibition at the Rotunda in Hong Kong’s Central district. “In the meantime, I shall continue with my painting as I have always done. I will not be rushed by death.”

Hong Kong’s old neighbourhoods get a new look

And that’s what he did. Until he became too weak around two years ago, he would pick up his brushes daily in the Kowloon flat he shared with his wife, the artist Choi Yan-chi, as determined as he was in the aftermath of a debilitating stroke in 2000.

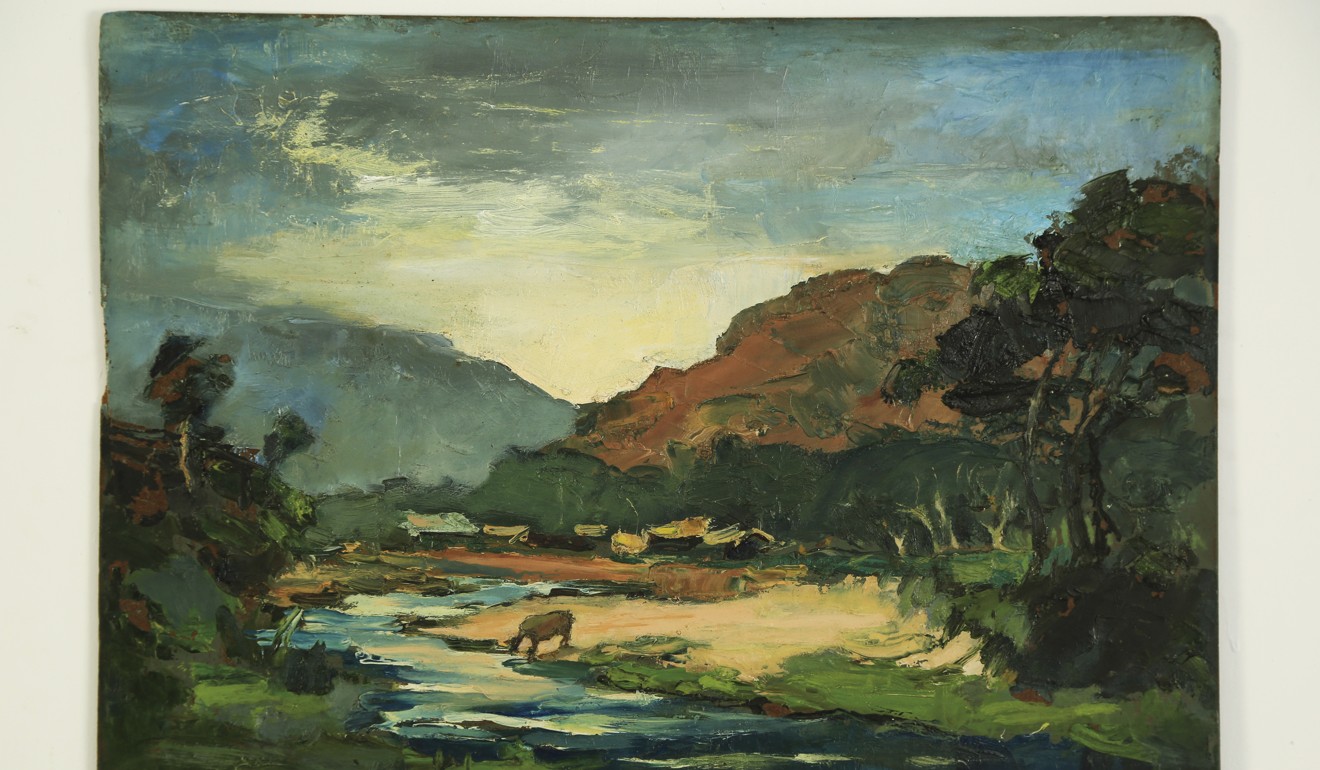

“I was coming out of a thick fog with a fire burning in my heart. I was not afraid of death any more,” he said, recalling his state of mind when he painted Out of the Valley (2000), an abstract composition with a bright red spot emerging from a grey mist.

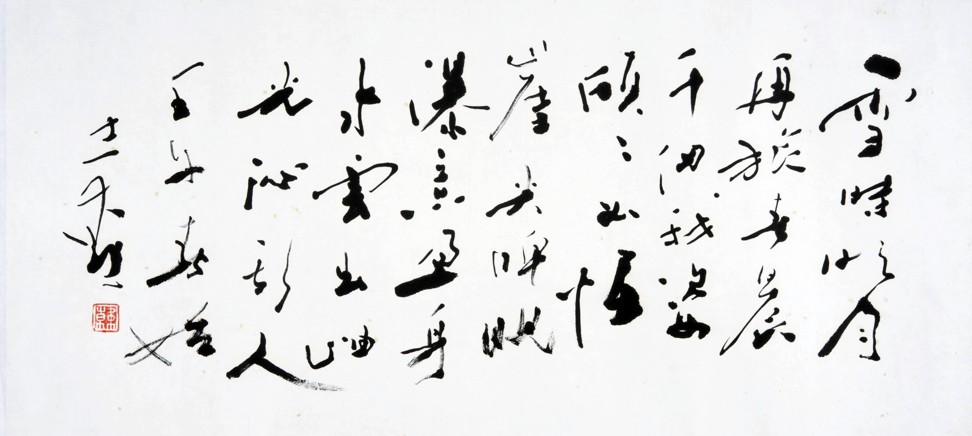

He could not remember a moment when he didn’t have a brush in his hand. Born in British colonial Hong Kong in 1922, the eldest son of a taxi driver went first to a traditional Chinese private school, a so-called Bok Bok Jai where old, bearded Confucian masters focused on getting young children to memorise classic Chinese texts and demanded unquestioning obedience.

Hon’s mischievous nature would land him on the receiving end of the master’s whip often. He did get something out of his early schooling, though – a superb command of the Chinese language and calligraphy.

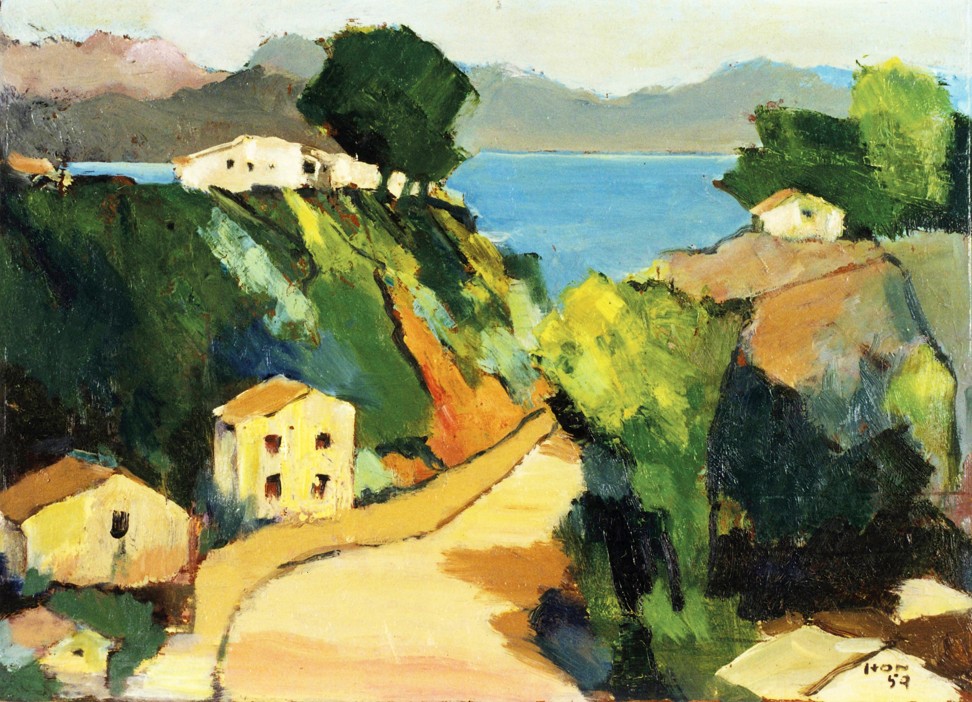

The post-war years were lean times, but a fertile period for Hong Kong’s burgeoning art scene.

Prominent southern Chinese ink artists like Lui Shou-kwan and Chao Shao-an moved to the city and taught there. In the 1960s, the Cultural Revolution in China and the riots in Hong Kong prompted serious reflections on the city’s identity. At the same time, young Hongkongwea were lapping up Western cultural influences such as the Beatles and pop art.

Hon spent every Sunday sketching with fellow artists who were all trying to bridge Chinese ink traditions with Western modernism. Shortly after American abstract expressionists such as Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell began to reference Asian calligraphy and brushwork in their art, Hon and fellow Hong Kong artists switched to abstract representation of their inner feelings while experimenting with different materials.

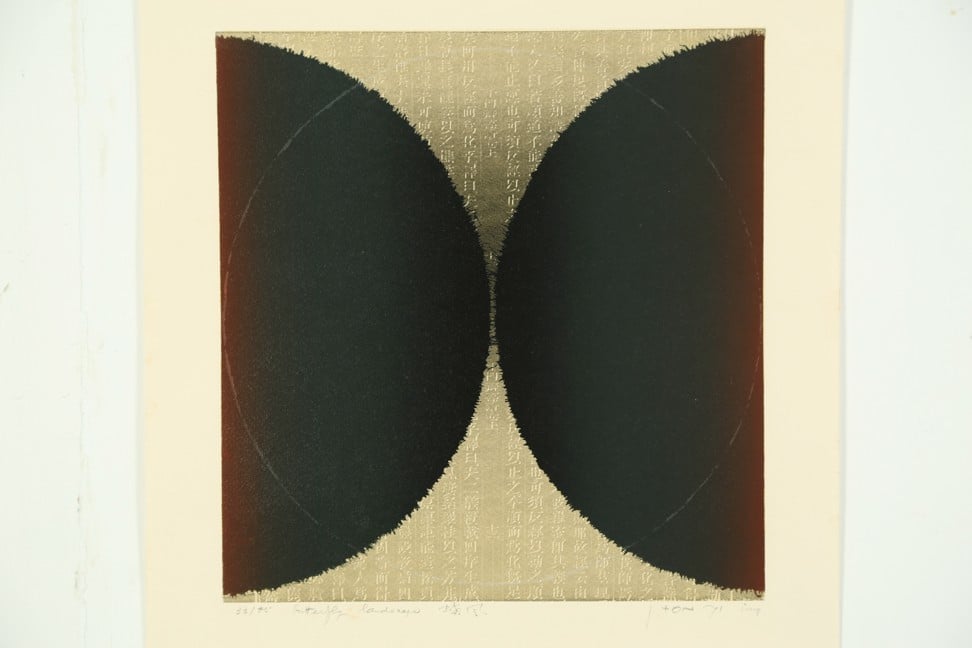

As a self-described hippy with a motorbike, Hon co-founded the influential Circle Art Group and started using airbrushes on acrylic.

Through the decades, he would move easily from acrylic paintings to Taoism-inspired screen prints, multimedia works and writing poetry. His was a generation that was really the first in Hong Kong to seek a new visual language to represent the melting pot of identities and cultures that they lived in, and to break away from traditional Chinese forms so radically that it would have left his old Bok Bok Jai teachers foaming at the mouth.

He was widely collected in the 1970s and 1980s, by the Museum of Art in Hong Kong and mostly collectors. The older Hon expressed disappointment that Hong Kong modernist artists were often overlooked, but not surprised. Having become part of China since 1997, the city was destined to stay on the margin as the world’s big powers determine the course of art history, he said.

The ancient Buddhist art of thangka has thrived in a Tibetan town, despite centuries of upheaval

He and Choi moved to Canada after the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown in Beijing, but moved back to Hong Kong in 2000, when he had a stroke.

He was taken to hospital a few weeks before he died on February 24. He was shown the catalogue of his upcoming retrospective at the Asia Society, which will open on March 12. He died in hospital surrounded by his family.

A Story of Light: Hon Chi-fun, Asia Society, 9 Justice Drive, Admiralty, 11am-6pm, Tue-Sun. Mar 12-June 9.