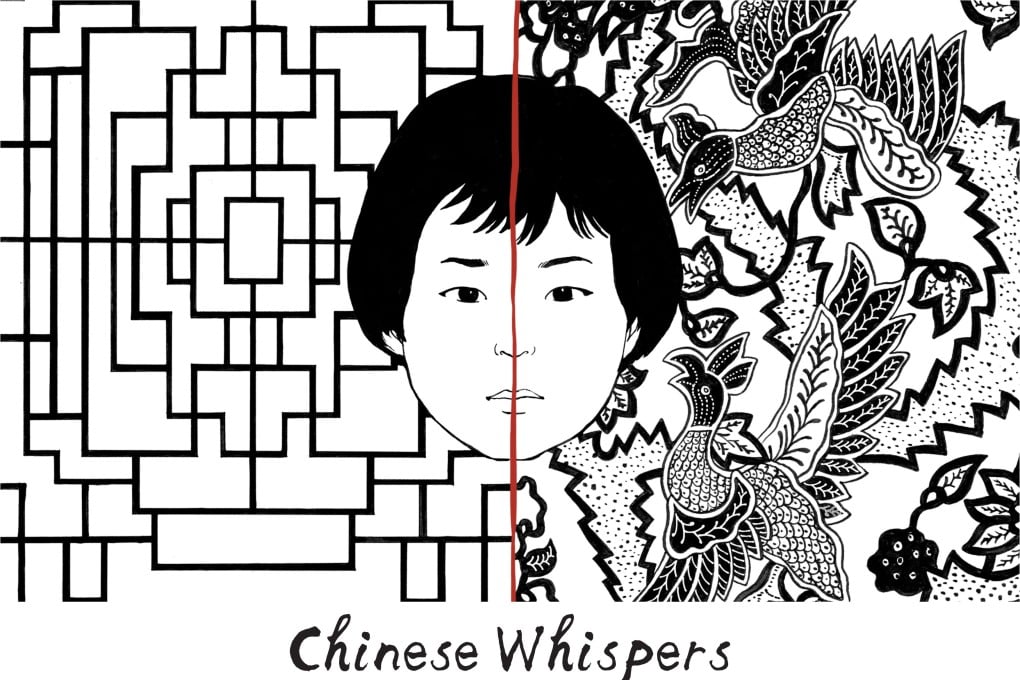

May 1998 Jakarta riots against Chinese: ‘We cannot heal what we will not face,’ author of graphic novel says

- Rani Pramesti’s Chinese Whispers recalls the racial violence against Chinese Indonesians 21 years ago and its impact on her community

- She wrote the digital novel to pierce the silence about events in which over 1,000 died, for fear failure to examine what happened could lead to a recurrence

With the 21st anniversary of the unrest falling this month, the arts producer is determined that the truth about the violent episode will never be erased and hopes her online graphic novel, “Chinese Whispers”, will help.

Rani, the founder of Rani P Collaborations, which focuses on intercultural exchange through storytelling, was 12 years old when the riots erupted. She was naive, she says, and could not recall ever being called “Cina”, a derogatory term for members of Indonesia’s Chinese minority. She had thought of herself simply as Indonesian.

As a child, she travelled around the archipelago with her parents, who hoped to instil in her a love of the country. She climbed mountains, swam rivers and scuba-dived in the oceans.

“I felt welcomed with open arms by the diverse society,” says Rani, who is of mixed Chinese and Javanese heritage. “So from there my love grew for my fellow human beings. It was a very idyllic childhood.”