The surprising truth about Aladdin: how Frenchman’s lacklustre tale ended up in The Arabian Nights and became a gem

- Frenchman translated tales from Arabic story collection A Thousand and One Nights, but ran out of tales to feed his 18th century readers’ appetite for more

- He wrote Aladdin based, he claimed, on a tale heard from a traveller; his story was unexciting, though, and owes its fame to later versions, including Disney’s

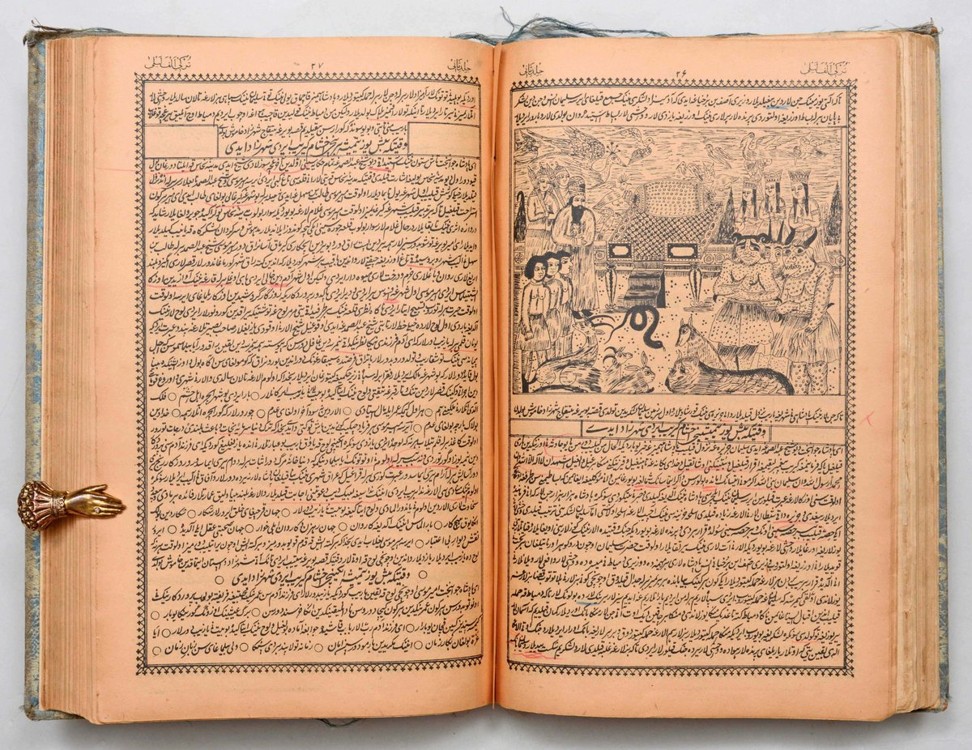

Quick! Name a story from the The Arabian Nights. If you answered Aladdin and the Magic Lamp, as most people probably do, you’d be wrong – at least technically speaking. There is no evidence that this beloved classic, now usually encountered in nursery versions, or on film, was ever part of the original collection of Arabic stories known as Alf Layla wa-Layla, that is “A Thousand Nights and a Night”.

What’s more, no early Arabic original has ever been found. Aladdin only exists today because of the 18th-century Orientalist Antoine Galland.

In the early 1700s, Galland acquired a manuscript of Alf Layla wa-Layla containing its first 35 and a half stories, which he loosely translated into French. Readers immediately went wild.

The first seven volumes of what he called Les Mille et Une Nuits generated Harry Potter levels of mania, in part because of an already established vogue for fairy tales – this was, after all, the same period when Charles Perrault was bringing out Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty.

Galland’s Arabic text comprised what scholars refer to as the “core” stories of The Arabian Nights, beginning with the prologue that explains their astonishing origin. After King Shahryar discovers his wife’s infidelity, he cuts off her head and vows never to be deceived again. For the next several years, he consequently marries a virgin each day, makes love to her in the evening and has her executed the following morning.

This goes on until his vizier’s clever daughter Shahrazad offers to become his new bride. On her wedding night, she entertains the king by starting, but not finishing, a story about a merchant and a demon. Eager to hear what happens next, Shahryar decides to keep the charming storyteller alive a little while longer.

You know the rest. Shahrazad never concludes a tale without immediately launching into a new one. What’s more, her characters often relate stories to one another and the characters in those secondary stories then tell still other stories. Because of all these branching and interlinked narratives – sometimes likened to nested Russian dolls or the arabesque patterns of Islamic art – The Arabian Nights constantly defers closure. The wonders never cease.

After seven volumes, though, Galland ran out of material to translate and searched in vain for another copy of Alf Layla wa-Layla. Even now, the late 14th-century Syrian manuscript he’d originally acquired – currently housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France – represents the oldest known written versions of stories that may have circulated orally for centuries, many having originated in Persia or India.

So where did “Aladdin” come from? In 1709, Galland reportedly heard it – as well as other stories, including Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves – recited by a traveller named Hanna Diyab. Afterwards, Galland scribbled three- to eight-page plot summaries in his diary, and later claimed that Diyab supplied him with a sort of written-out, but now lost, account of Aladdin.

Whatever the case, Galland – like any traditional singer of tales – adapted and shaped what he had listened to, then published his 100- to 200-page versions in later volumes of Les Mille et Une Nuits.

But when compared to some of his earlier “core” stories, the 1712 “Aladdin” comes across as lacklustre and unexciting. Disney’s two screen versions, the 1992 animated feature and this spring’s live-action film, are actually much more satisfying. Galland’s Aladdin is no kindhearted “diamond in the rough”, he is the slacker son of a hard-working tailor in “the capital of one of China’s vast and wealthy kingdoms”.

A nameless North African magician, not a vizier named Jafar, apparently chooses him at random to retrieve the magic lamp. Instead of one genie, Galland has two, and it’s the one attached to a special ring who actually releases Aladdin from his underground prison.

When the young man falls in love with a generically beautiful but colourless princess, he does not bother trying to court her: he just sends his mother to the sultan with a bowl brimming with precious gems. Money talks.

After the princess is nonetheless betrothed to the vizier’s son, Aladdin employs the lamp’s genie to prevent the consummation of the marriage, which is eventually annulled. Further demonstrations of gaudy, conspicuous extravagance – such as the construction of a fabulous, jewel-encrusted castle – convince the sultan that here is the right husband for his daughter.

At this point, the evil magician reappears, regains control of the lamp and transports the castle and the new Mrs Aladdin to North Africa. With help from his backup genie of the ring, Aladdin hurries to the rescue, then compels his wife to do all the dirty work: pretending to be infatuated with her captor, she secretly poisons his wine. The dead man’s younger brother duly seeks revenge but is quickly dispatched, this time by Aladdin himself.

In John Payne’s 19th-century version of Galland’s story, Aladdin finally ends up as sultan; in Husain Haddawy’s modern translation, the princess succeeds her father but “transfers the supreme power” to her husband. And in Yasmine Seale’s excellent recent edition from Norton, the princess inherits the throne but “shares her power” with Aladdin. In the latest film, Princess Jasmine deservedly becomes the actual sultan.

Through its use of foreshadowing and prolepsis, The Arabian Nights consistently fosters a fatalistic sense that no one can escape his or her destiny. This isn’t a particularly congenial philosophy. By contrast, the two Aladdin films emphasise the paramount human need for freedom. Jasmine, especially in the live-action movie, could be any accomplished modern woman facing a glass ceiling.

Aladdin feels trapped by his poverty, denied happiness and love because of class barriers. The genie is literally the slave of the lamp, his power bracelets actually manacles keeping him obedient to an endless round of masters. As played by Will Smith, he yearns to say, like civil rights marchers of the 1960s, “I am a man!”

In both its film versions, Aladdin shows us the consequences of living an inauthentic life, a life of existential bondage. All the characters feel forced – constantly, frenetically – to dissemble, lie and pretend to be what they are not. Only at the story’s climax do the masks come off and true selves stand revealed.

In The Arabian Nights, Shahrazad and many other characters tell numerous marvel-filled tales to save their lives. Disney’s Aladdin, however, recognises that, in the end, only the truth will set you free.