Review | Poetry, drama, tragedy in images of China and Soviet Union shot by Chinese photojournalist 1980s and ’90s

- Liu Heung Shing, a Pulitzer Prize winner, enjoyed a unique advantage in China as a Chinese person with local insight but the freedom of a foreign correspondent

- The Hong Kong photojournalist captured images both of daily life and big events, from the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown in Beijing to the fall of the Soviet Union

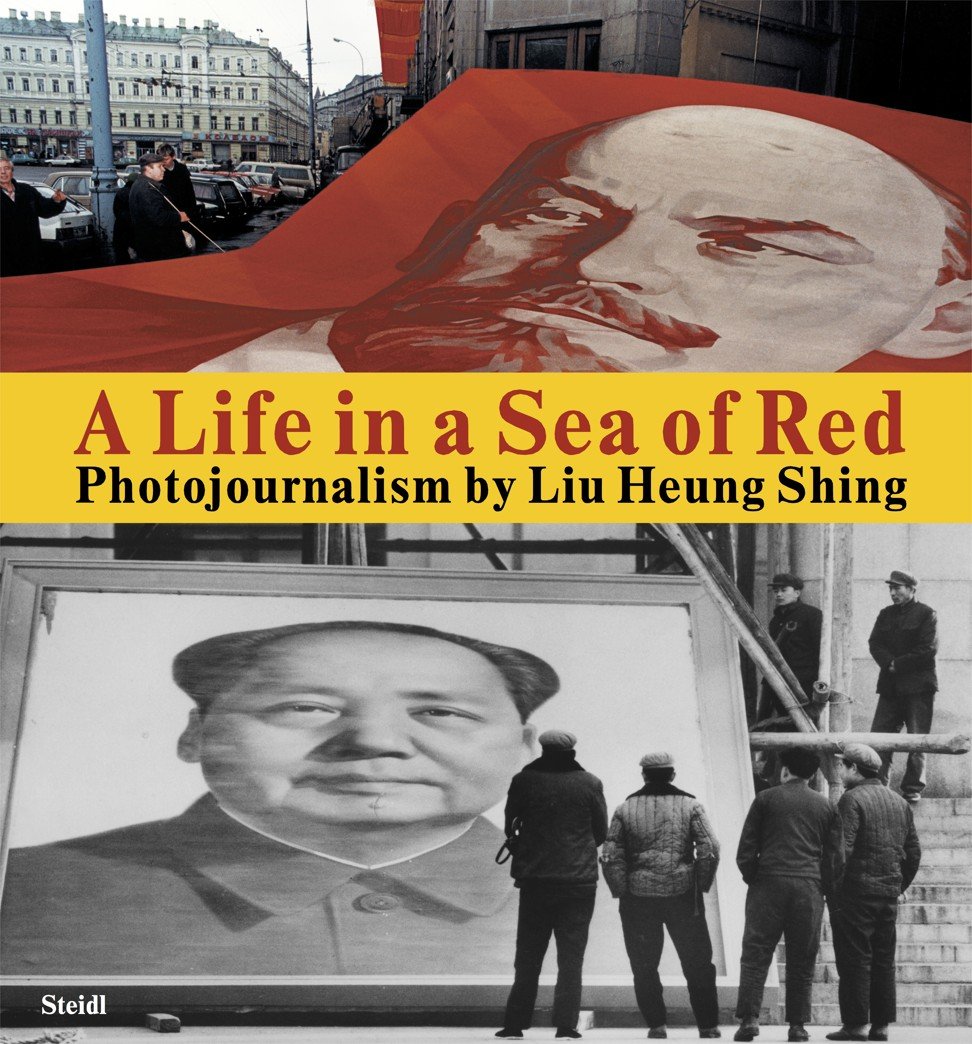

A Life in a Sea of Red: Photojournalism by Liu Heung Shing, by Pi Li, Christopher Phillips, Geoff Raby and Liu Heung Shing, Steidl, 5/5 stars

A Life in a Sea of Red, which will be launched globally this month, is the only book to combine Hong Kong photojournalist Liu Heung Shing’s work from the world’s two communist superpowers, the Soviet Union and China.

Together, these states once housed a quarter of the world’s population and acted as a powerful counterforce to the West. But by 1991, the two allies had gone in opposite directions. The impoverished USSR splintered into more than a dozen independent states, while China consolidated power and became an economic giant.

Liu, a Pulitzer Prize winner, used his lens to catch the poetry, drama and even humour of daily life under these regimes – and what happened when unrest inevitably boiled over.

The hardships of Soviet life can be seen in Liu’s snapshots of empty supermarkets, striking coal miners, pro-democracy marches, and a candlelit vigil after a massacre in Tbilisi, in what was then Soviet Georgia. But he also finds moments of beauty, such as a soldier smelling a flower, or a young girl being outfitted for a Russian ballet.

Liu spent much more time covering China, starting in the post-Mao era in the late 1970s. His images from the 1980s depicted the tedium of everyday life (peasants harvesting cabbages at a commune), but could also be heartwarming (people singing, dancing, and enjoying their first Coca-Cola), or wryly funny (Richard Nixon jokingly handing out drinks on a Chinese train).

The most recent images show the China we know today – a vastly different country of designer fashion shows and gleaming high-rises.

The book is cleverly curated to emphasise Liu’s message. The images in the first half, which is about life under communism, are almost all in black and white or use muted hues. Then suddenly, on the first page of the chapter “Tian’anmen Turmoil”, the images burst into vivid full colour. In shots of the protests of June 1989, scarlet protest banners, olive army helmets, and the white Goddess of Democracy are depicted against big blue skies.

Another image by Liu in the M+ collection is of a couple sharing a bicycle – a slender young lady perched in a draped dress, her hand around her partner’s waist. It would be a romantic portrait – except that it is June 5, 1989, and they are hiding nervously under a bridge as tanks rumble above them.

This snapshot is an example of Liu’s talent for capturing touching personal moments amid political turmoil and economic change.

It is heartening to see Liu’s more sensitive works included in a Hong Kong government-funded collection, at a time when freedom of expression is being debated.

Keep an eye on those two photos. As time goes on, they may act as a barometer of how far artistic and journalistic freedom in Hong Kong can go.

Pi Li, a curator at M+ and the main author of this book, describes Liu’s unique role in bridging cultures. Liu was one of the few photographers of that era who covered China with the local insight of a Chinese person, but also the freedom and global exposure of a foreign correspondent. His first assignment, for Life magazine, was covering Mao Zedong’s death.

From rural Xinjiang to glitzy Shanghai, Liu “records the living conditions of various social strata after the Maoist era, and dispels the insidious bias in news reporting”, Pi Li writes.

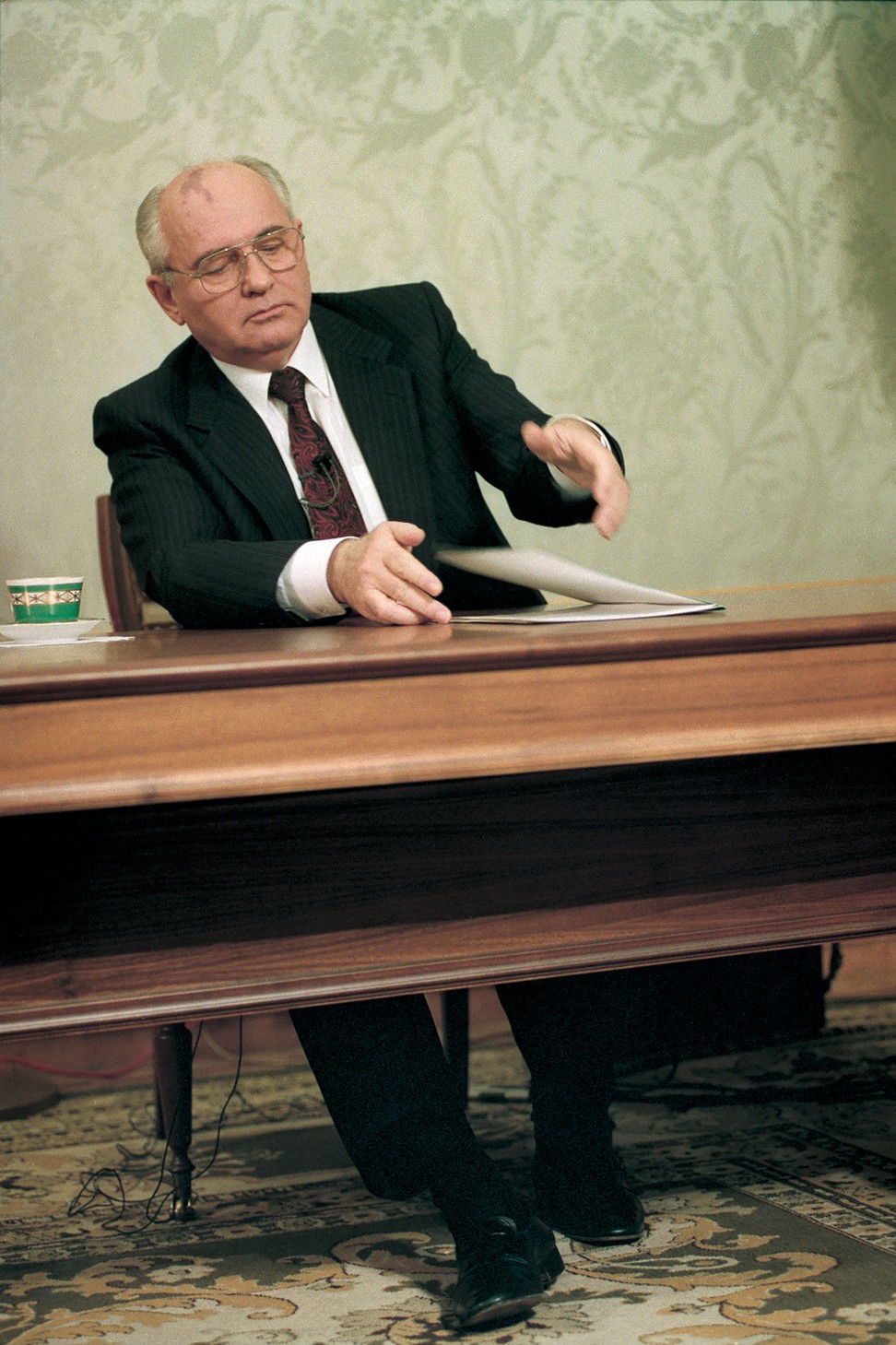

Liu’s work was shot painstakingly on film, and every grain of detail comes out in the luxurious thick paper and large-format printing of this hardcover volume. You can see the blur of the page as Gorbachev slams shut his resignation speech – which Liu snapped at the exact second that the Soviet Union was doomed to non-existence.

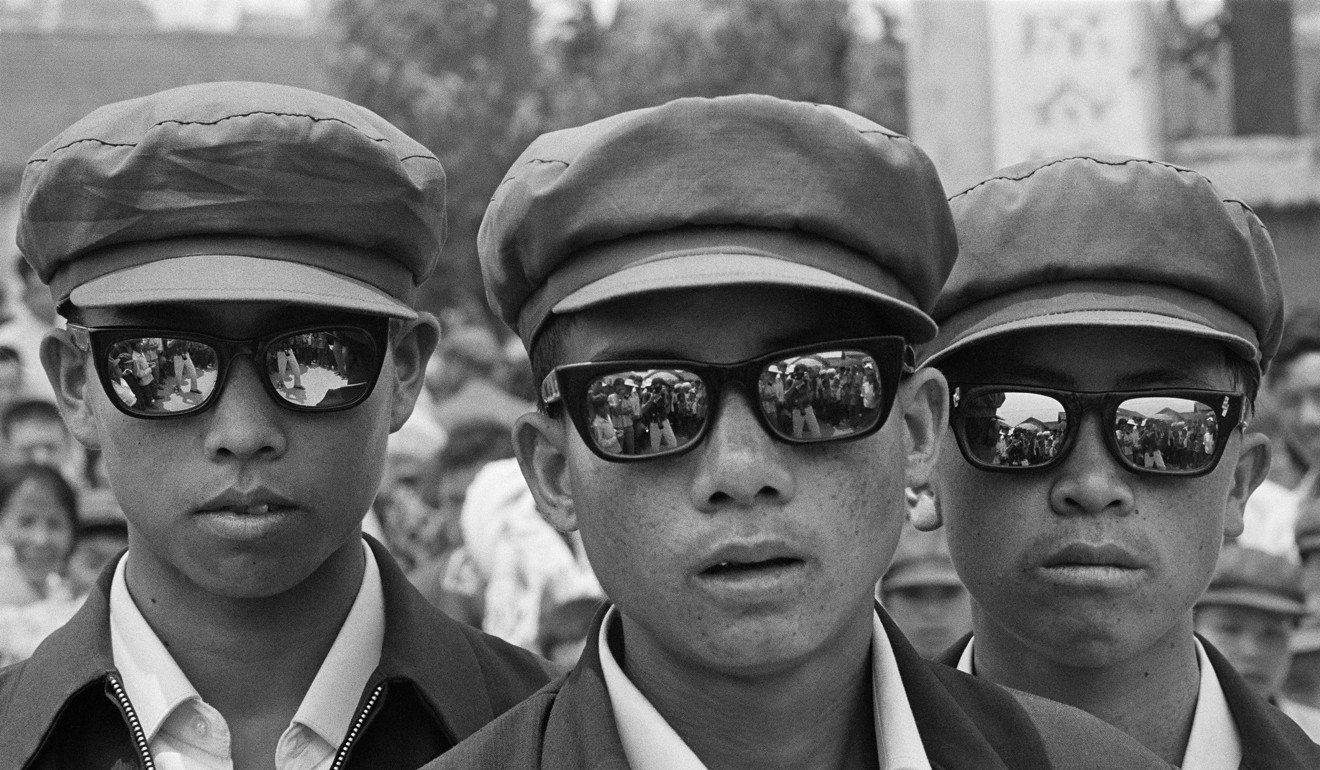

And if you look carefully, you can see Liu himself, reflected in the cool sunglasses of the three young men sporting Mao caps in a photo titled “The Style Brigade, Yunnan”.

Life in a Sea of Red is ultimately a history book. As Liu writes in the epilogue, “the marks left by the tanks’ caterpillar tracks on the Boulevard of Heavenly Peace have long been repaired, and Russia is now a nation where communism is nearly buried”. Momentous events like that live on through the journalism of people like Liu, and in people’s memories.

Hong Kong is part of the collective memory of the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, as the only city on Chinese soil where mass vigils mark the June 4 anniversary each year.