Artists make their art sustainable, and their art about sustainability as they catch up to ‘ecological crisis’

- A growing number of Hong Kong artists are addressing sustainability issues not just in the theme of their works, but in the practise of their art making

- Each brings their own inimitable style, from the materials they use to the wide-ranging concepts they cover

But a growing number of Hong Kong artists are addressing a wider category of issues affecting all humankind: sustainability, environmental protection and coexistence with other species. Often, their strategies are just as radical, if not more so, than the political protesters.

Artists all over the world are trying new ways to halt our lemming-like procession towards irreversible climate change. In doing so, they are challenging pre-existing ideas of what art means, as well as the way art is produced and presented.

How two green schools in Hong Kong are teaching sustainability to children

In Hong Kong, there is a long tradition of art with a message of harmony between humans and nature – it is an essential spirit of classical Chinese painting – and some artists are now committing their entire practice to ecological issues, each in their own inimitable ways.

Take Zheng Bo for example. The artist from Lantau Island, who teaches at City University of Hong Kong’s School of Creative Media, believes so much in pushing the boundaries of cross-species coexistence that he carries his Yorkshire terrier in a bag wherever he goes. (It takes an especially sedate dog for this to work in Hong Kong, and I have seen his sit through a five-course dinner with better table manners than most people.)

The queer artist’s video series Pteridophilia (2016-18) was one of the most memorable pieces at last year’s Taipei Biennial. It imagines a world where human beings can live with other species – in this case, ferns – not just for rational, utilitarian reasons, but also for pleasure. The series features a cast of naked young men making love to native plants in a Taiwan forest where Japanese and Chinese soldiers used to survive by eating edible plants.

Zheng has a new work called You Are the 0.01% at Oi, the Hong Kong art space on Oil Street in North Point.

Zheng has also just finished a project in Kyoto where he and a team from the Kyoto City University of Arts Art Gallery looked into the history of the Suujin area, a working class neighbourhood near Kyoto Station with a declining population. The project considered the possibility of an urban experiment in which weeds and wild animals are allowed to coexist with human inhabitants, rather than be seen as intruders.

Zheng admits he is hardly a lifelong eco-warrior, but now is an advocate for change.

“I was back in Beijing from 2010 to 2012 and the pollution was bad. That is probably when I started feeling strongly about the environment. And in 2013, I was commissioned to work on a project in Shanghai that involved preserving an abandoned cement factory and the wild plants that had taken over it. I was late [in taking action], really. As are many artists. Artists used to be truly avant garde but when it comes to the ecological crisis, we are way behind,” he says.

Eco-art should be more than just the subject matter, Zheng adds, citing the substantial environmental impact of art production, shipping and of artists flying frequently to exhibitions. “We have to change the way we operate. The way we do things now is so costly to the environment,” he says.

For the Kyoto project, exhibits are placed on temporary tables made from salvaged wooden boards elevated by stacks of bricks, as the team avoided the use of new materials for presentation’s sake.

Zheng is also cutting back on flying. “I use the word ‘useful’ a lot these days. If someone asks me to fly to an exhibition, I’ll agree to it only if I can be useful, such as giving talks or conducting workshops. If it is merely to install the artwork and attend the opening party, there is no point,” he says.

There is a limit to how much you can convey about farming when you sell someone a head of lettuce. There is so much to think about, such as the irony of trying to forge a harmonious relationship with nature while trying to protect your crops and yourself from pests

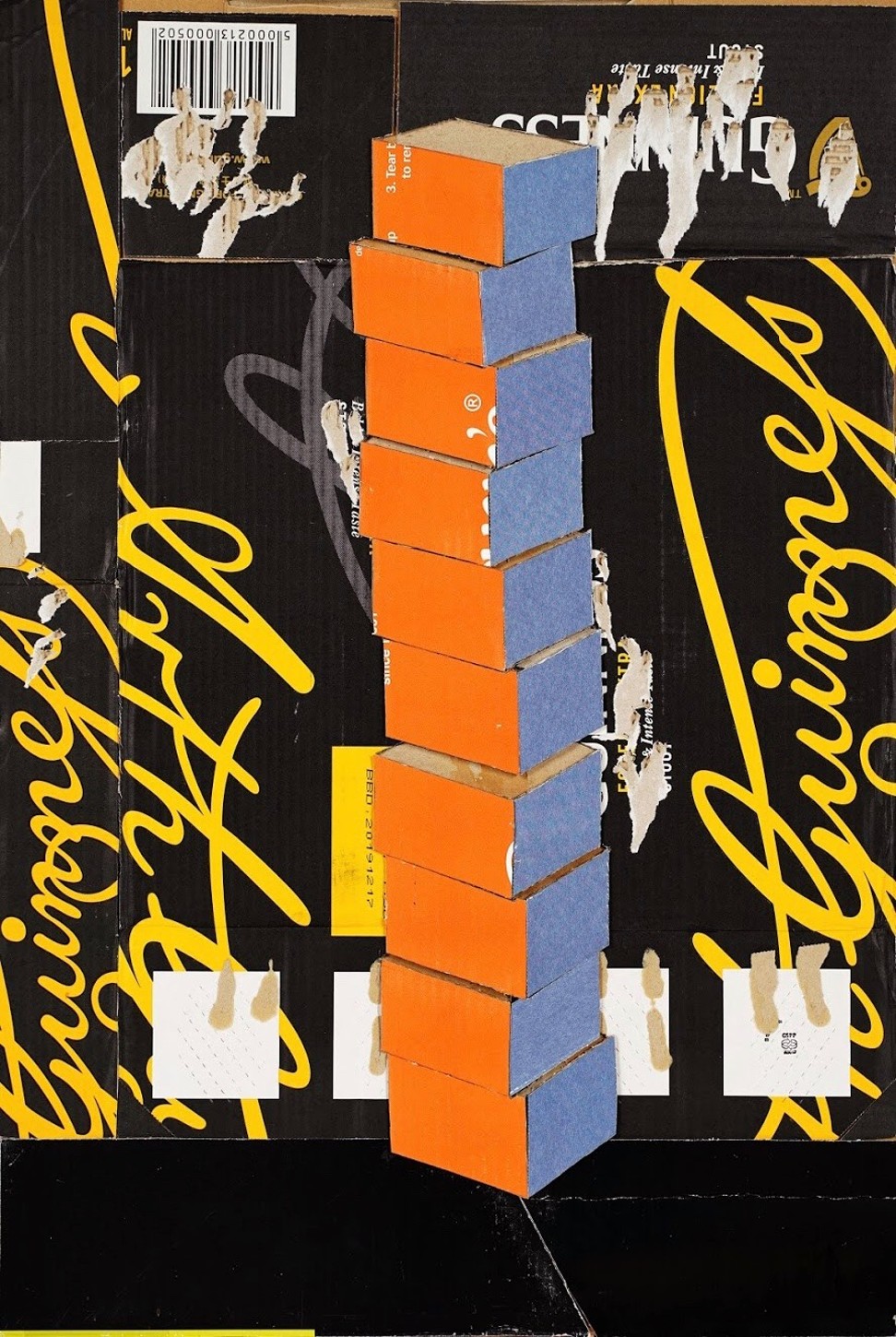

A belated awareness of the use of materials in art is becoming more widespread. Interesting examples abound, including that of Lee Boon-ying, former director of the Hong Kong Observatory (HKO). Lee, who went to art school after he retired in 2011, now makes art using just cardboard and found materials.

“My ‘cityscapes’ are collages made with cardboard, a material that resonates with people growing up in Hong Kong and which reflects the fragility of our inheritance,” he said during the “Moot Point” group exhibition last month at Aco Art Space in Wan Chai, where his cardboard art was on show. “By choosing cardboard, I also hope to reduce the carbon footprint of my work. As a former director of the HKO, I naturally feel very strongly about climate change.”

Last year, Hong Kong sculptor Parry Ling Chin-tang founded Post Tree Lifestyle to turn typhoon-felled trees into artwork and furniture. And beyond visual art, the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra has been developing “eco-huqins” since 2005 – recyclable polymer versions of Chinese string instruments traditional made from python skin.

Natalie Lo Lai-lai belongs to a different category of environmentally conscious artists. She makes videos and installations inspired by her life on a farm in Yuen Long.

Lo, a former travel writer, has been a keen hiker since her secondary school days but was never particularly “green”. Her transformative moment came in 2010; she quit her job and joined a group of young activists who helped hundreds of Choi Yuen village residents in their attempt to block the bulldozers that would ultimately raze their homes to build a high-speed railway to China.

As well as being a harbinger of larger social movements associated with the speeding up of Hong Kong’s integration with China, the failed resistance highlighted the right to an alternative, slower, rural lifestyle that has long been written off as an option in one of the world’s most densely populated cities.

Lo and other activists became attracted to Naoki Shiomi’s “Half Farmer, Half X” idea, first introduced in Japan in the 1990s to encourage more people to return to the land (the “X” refers to any supplementary, non-farming activity). Lo joined a few others to set up Sangwoodgoon in Yuen Long, a farming collective that has been steadily producing vegetables and rice on a plot of roughly 15,000 square feet (1,400 square metres) since 2014. Her “X” used to be writing and editing; lately, it has become art.

“There is a limit to how much you can convey about farming when you sell someone a head of lettuce,” she says. “There is so much to think about, such as the irony of trying to forge a harmonious relationship with nature while trying to protect your crops and yourself from pests, especially the infestation of red imported fire ants [we have] on the farm.”

Lo decided to study a master of fine arts at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and her art practice has allowed her to express the emotions and paradoxes that germinate on the farm.

Her works often feature the tension between imagined ideals and harsh realities. Voices from Elsewhere (2018) looks at the uneasy relationship between the historic fish farms in nearby Tai Sang Wai and the bird population. Glacier (2016), filmed in Europe, considers global warming, consumerism and tourism.

Recently, the WYNG Foundation commissioned Lo to make a project about Sangwoodgoon called “The Days Before Silent Spring”. It was an opportunity for her to look back on nearly a decade on the farm as the collective is poised to start a new farm and education centre nearby.

“I still find farming very hard. Sometimes, I worry about thinking too much as an artist and getting distracted from becoming a better farmer,” Lo says. “But I am committed to this lifestyle and I want to find a way to make this a viable alternative in Hong Kong. I still travel into town to join protests sometimes, but this has become my main mission.”

Meanwhile, the Hong Kong Museum of Art will reopen in November with new green features and waste reduction practices. The reopening follows a four-year expansion and refurbishment project aimed to reduce the museum’s harmful impact on the environment.

“We considered whether to tear down the old, pink facade but in the end, we simply put a new ‘coat’ on to reduce construction waste,” explains Maria Mok Kar-wing, the recently promoted museum director.

The museum’s new smart, grey exterior is a modular system made with fibre boards that insulate against heat, cutting down on energy consumption.

“Each year, that will amount to 123,000kg in carbon emissions,” Mok says.

Additional features include 1,000 square metres of green landscaping, including a vast green roof and a new, smarter air-conditioning system.

“We are increasingly concerned with excessive consumption within the museum, and we encourage our service providers to reduce waste,” Mok says. “We will also print less paper-based brochures and encourage visitors to use our mobile apps instead. For those without smartphones, we will have tablets available for lending out.”