Heritage conservation in China: why ‘Daughter of Dunhuang’ devoted her life to keeping Buddhist caves and relics alive

- Chinese archaeologist Fan Jinshi has spent more than 50 years protecting the Dunhuang caves from erosion, overtourism and even Mao’s Red Guards

- Her recent work with the British Library has seen the site’s exquisite cultural heritage digitalised and put into archives for the global community to enjoy

Anyone with more than an ounce of interest in Dunhuang will have heard of Fan Jinshi.

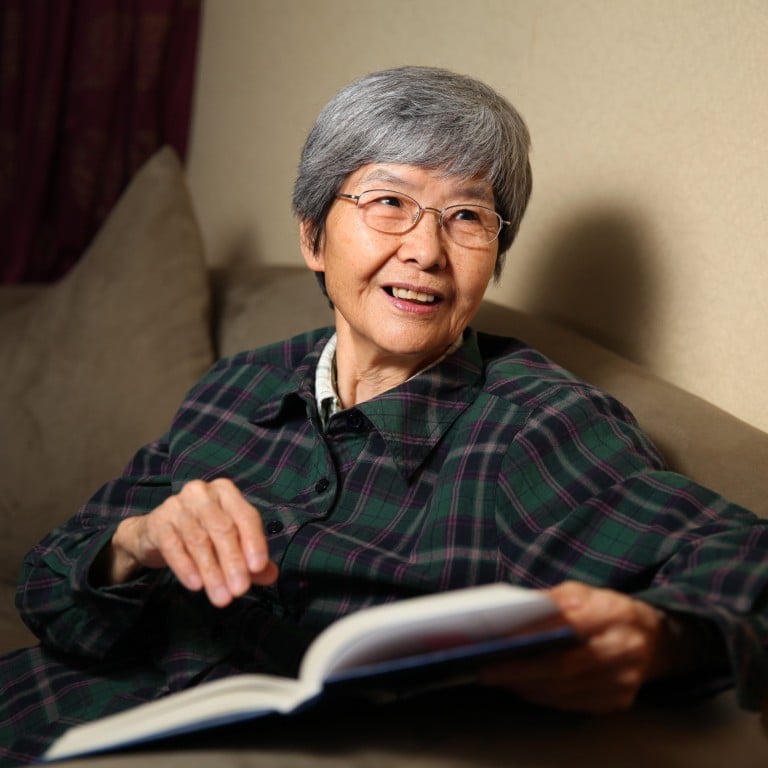

Now 81, the Chinese archaeologist who has spent more than half a century researching and preserving the caves at the heart of the ancient Silk Road in Gansu province is known as the “Daughter of Dunhuang” in her field, though “protector” is probably a more fitting description.

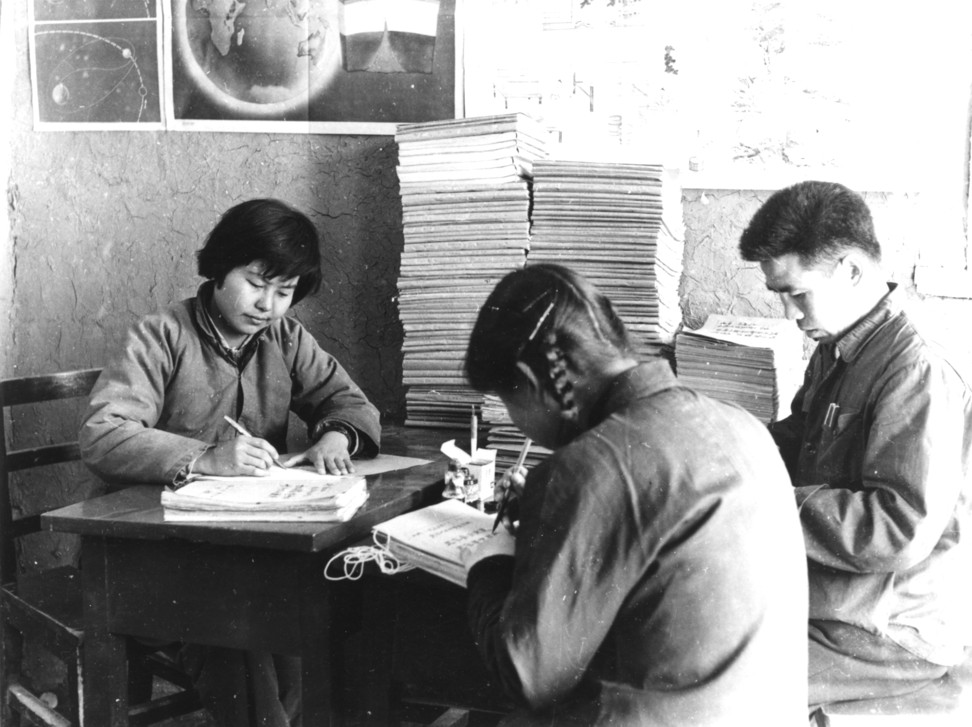

Fan has been studying the historical site since the early 1960s, first as an archaeology undergraduate from Peking University, then as a conservationist when she became the deputy director of the Dunhuang Research Academy in 1984, which serves to protect the ancient site from erosion and collapsing.

“It is over a thousand years old. It is an old person, an extremely vulnerable old person. It has a lot of illnesses. If you are a little careless, it would be gone. Gone forever,” Fan says.

Fan’s preservation efforts are widely recognised. In October, she received the Lui Che-woo Prize in Hong Kong for her contribution to preserving important cultures for the world. She also received the national honorary title of “outstanding contributor to cultural relics protection” in China a month earlier.

“Dunhuang caves must exist forever. It’s not just for our generation. We should pass it on, intact, to our children and grandchildren. We shouldn’t take away the rights of our children and grandchildren,” she says, adding that she would be “the sinner of history” had she let the caves be destroyed.

Fan’s love affair with Dunhuang began when she was sent to do an internship in Dunhuang in 1962, a year before graduating from the Peking University’s archaeology department. She was particularly interested in the art created during the Northern Dynasty (AD386-581) and Tang dynasty (AD618-907) because it represents the very best of artistry and techniques in both Dunhuang and Chinese history, she believes.

“From the very beginning, it seemed to me that the whole [of Dunhuang] was a living museum, and fate placed me in front of these great arts,” Fan says.

But destruction also came in other forms. Between 1966 and 1976, China was gripped by the Cultural Revolution. During the decade, Chinese youth formed paramilitary groups known as the Red Guards to harass and attack elder intellectuals and destroy pre-communist Chinese arts and architectures.

Fan recalls in her memoir, published in October, that while there were sectarian struggles within the Dunhuang Research Academy, the consensus among them was to protect the relics. She and her colleagues sealed off the caves in case the Red Guards would come. And they did.

Fan explained to them that the country had rules regarding relic protection and asked them to stay calm. Unexpectedly, the young people said: “Don’t be nervous. We just want to take a look at Dunhuang.”

It tuned out the Red Guards were also fascinated by the legendary beauty of Dunhuang. Luckily, the curiosity helped keep the caves intact.

While Dunhuang survived the Cultural Revolution, Fan’s father didn’t. In 1968, like many intellectuals at that time, he committed suicide after being humiliated and interrogated. When she returned to Dunhuang, some of her colleagues blamed her for “mourning the antirevolutionary”.

It was one of the darkest periods in her life. What saved her from utter despair, she recalls, was when her thoughts turned to the sculpture of a sitting Buddha with a serene smile.

The world is meant to communicate [and] we can learn from them. Therefore, the world should exchange and learn from each other, and then cultures can flourish

One of the biggest threats to the area has also been overtourism. Fan is known for her fierce objection to Gansu province’s plans to transform the caves into an entertainment theme park back in 1998. She argued that the government should not be allowed to make money by exploiting cultural treasures.

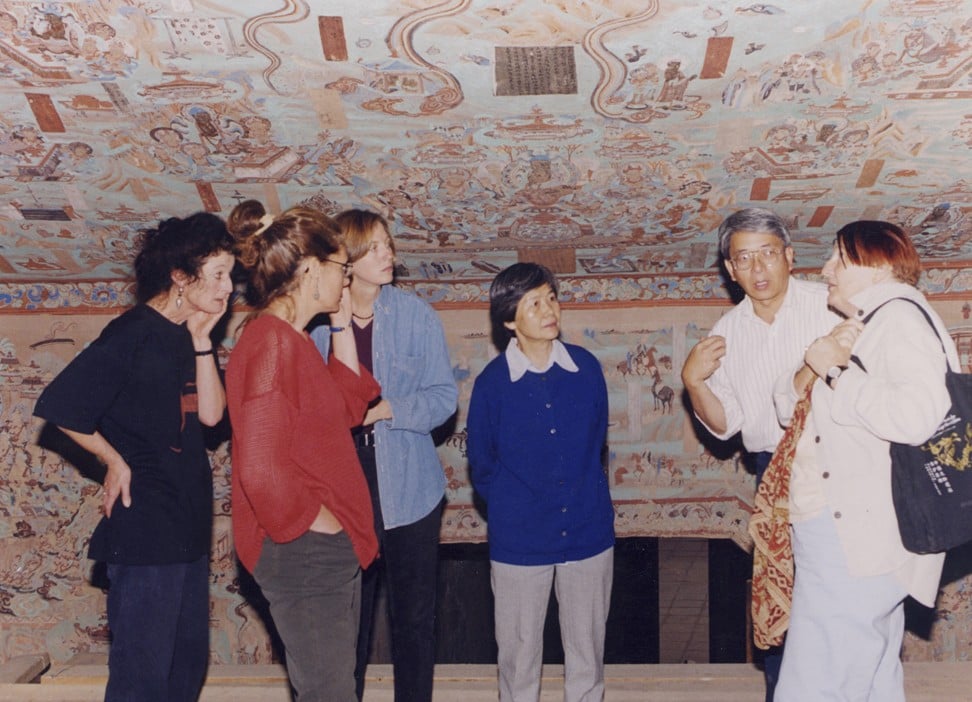

Other than physically rescuing the Dunhuang caves, one of Fan’s biggest contributions to their conservation is setting up a digital archive of the caves in the 1980s that would store images of the relics permanently.

International collaboration has also helped usher her conservation efforts into the 21st century, with the academy acquiring advanced conservation technology and management skills from other countries that have helped with site planning, scientific research, environmental monitoring and controls, and visitor management. The methods were later applied to conserve other cultural heritage sites in China and around the world.

“The world is meant to communicate [and] we can learn from them. Therefore, the world should exchange and learn from each other, and then cultures can flourish,” Fan says.

In addition to conservation, Fan has also achieved academic success, having published a large number of research papers and chronicling the Dunhuang caves through several different Chinese dynasties.

Fan retired as the president of the Dunhuang Research Academy three years ago. Reflecting on her life and career out there in the harsh desert, she has no regrets.

“I was given a chance to do something [to promote] world cultural heritage,” she says. “My life is worthwhile. I have done a good thing for mankind.”