A question of identity: the Chinese Jews of Kaifeng, and photographer’s encounter with a community whose roots go back 1,400 years

- When photographer John Offenbach heard there were Chinese Jews living in Kaifeng, Henan province, he ‘had to visit’ them to shoot portraits for his show JEW

- His images from around the world explore what it means to identify as Jewish; in Kaifeng he was shown a tablet with the Ten Commandments written in Chinese

Award-winning photographer John Offenbach looks at one of the portraits featured in his exhibition “JEW” at the Jewish Museum in north London.

“I liked this woman because she talked about discovering her Jewish heritage from an official document,” he says.

One theory about their presence in China is that they are descended from merchants who travelled there from Persia and elsewhere in the Middle East. There may have been Jews in Kaifeng since the 7th century, and it is estimated there are around 1,000 people living in the city today of Jewish heritage.

Li discovered her ethnicity as a child, when she found the word “Jew” in her hukou, or household registration document.

“Mrs Li told me she became interested in finding out more about her background,” Offenbach says. “During her 20s she would go to Shanghai, where there were resources for her to learn about her ancestry. She bought books there and read up on Judaism.”

Li’s portrait is one of 34 images on display at the Jewish Museum. London-based Offenbach spent four years travelling the world in search of hidden or little-known Jewish communities, and taking photographs of Jews from different backgrounds.

“I wanted to explore the nature of what it means to identify as Jewish today,” he says. “I’m a white, middle-class Jewish man from north London. I live in a bubble. I wanted to show people that Jews can come from myriad walks of life.”

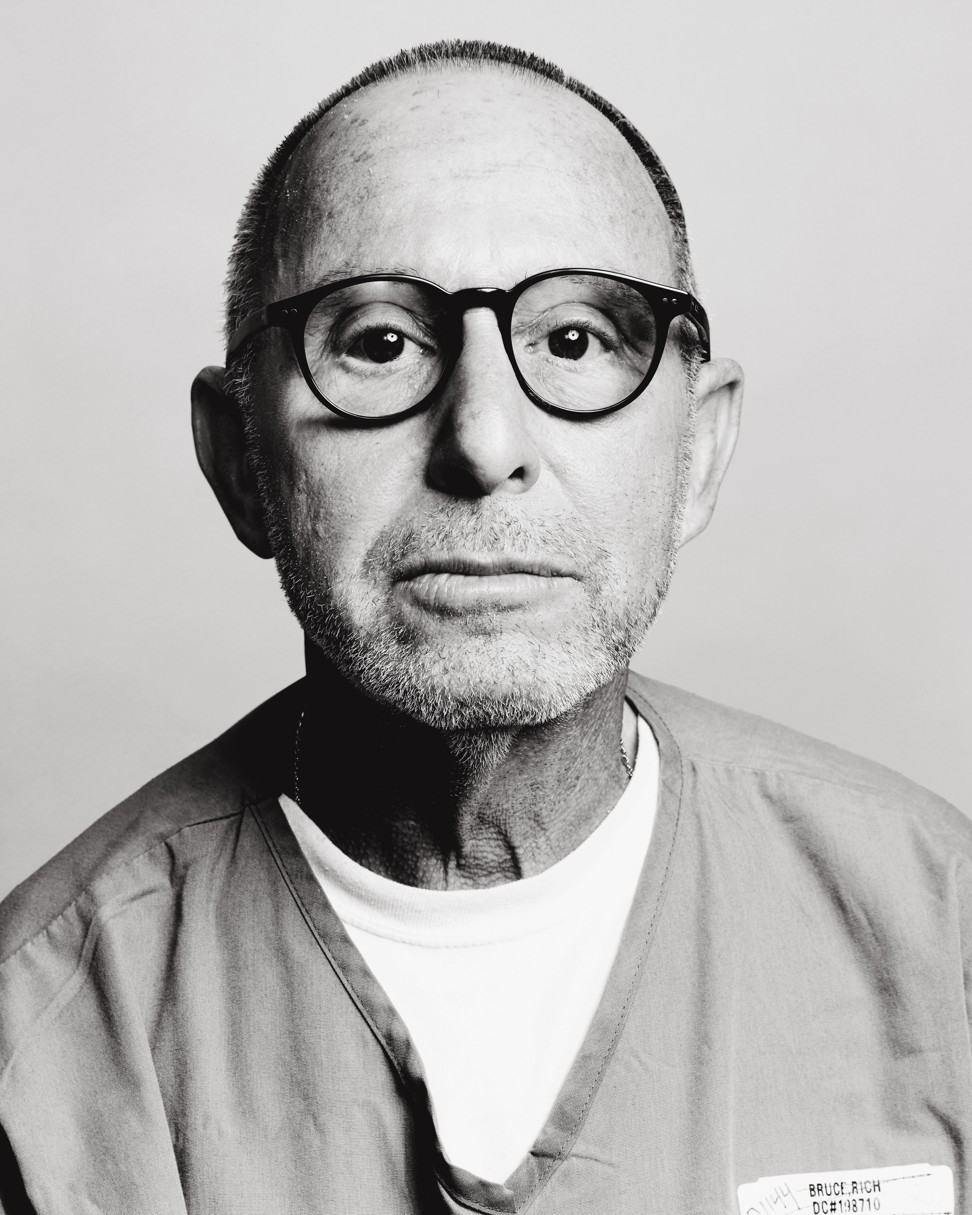

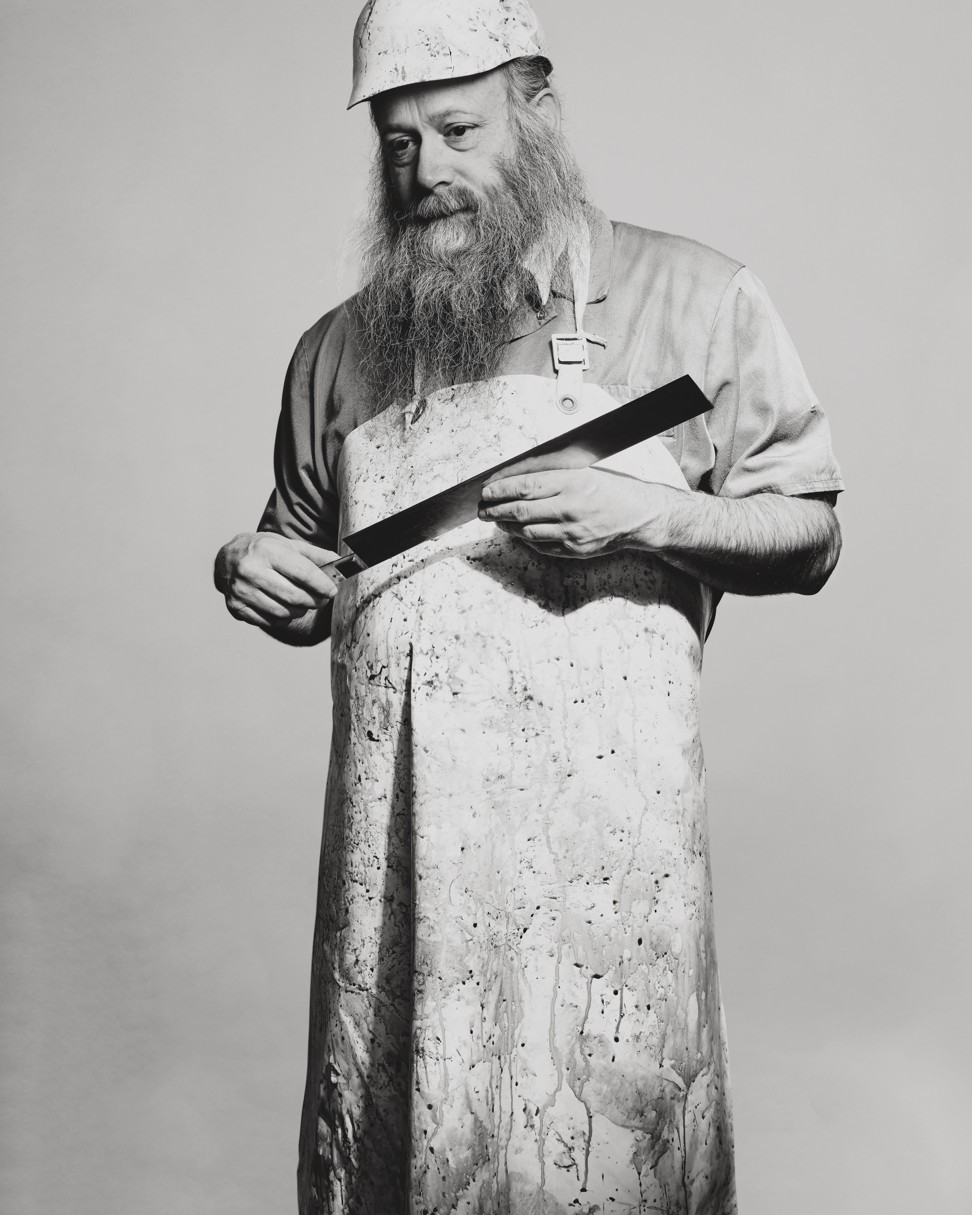

His large-format photographs run the gamut from religious to secular Jews, and rich to homeless Jews. There are Jews of colour, Jews with disabilities, victims of crime. A convicted murderer makes full eye contact; a former director of Mossad, Israel’s intelligence service, looks askance. A book, also called JEW, featuring Offenbach’s full set of 120 images was launched at the exhibition’s opening.

Another of Offenbach’s portraits, “Kaifeng Jew I”, shows a man wearing a traditional skullcap – known as a kippah, or yarmulke.

“This man had his DNA tested and discovered he could trace his roots back along the Silk Road to the Middle East,” Offenbach says.” I knew there were Jews in Ethiopia and India, but I did not know about Kaifeng, China. Once I read about the community there, I had to visit.”

A Beijing-based cousin of Offenbach’s, who speaks fluent Chinese, acted as his “fixer” and Offenbach visited Kaifeng in September 2016.

“I met around 20 members of the Jewish community there, who were extremely welcoming to me,” he says.

Dr Mukta Das, a research associate of the London-based SOAS Food Studies Centre, whose work covers the impact of historical and present-day immigration on Chinese food culture, offers an insight into Kaifeng’s long-standing links with Judaism.

“The importance of the Yellow River to the north of the city, which cuts the modern-day province in two, is something that has defined the identity of the major capital cities in Henan since the beginning,” Das says.

“Firstly, Kaifeng would have flooded often, and would have been built and rebuilt. But the river brought a lot of wealth into Kaifeng, particularly when the imperial Grand Canal was built and Kaifeng become a major commercial centre.

“From the 1100s, there were all sorts of [established] foreign communities in Kaifeng, for example Muslim, Persian and Jewish traders. A synagogue was built and a kosher butcher tradition was established.”

The synagogue was destroyed in 1860, members of the community married into local Chinese families and observance of Jewish traditions dwindled.

From the 1100s, there were all sorts of [established] foreign communities in Kaifeng, for example Muslim, Persian and Jewish traders. A synagogue was built and a kosher butcher tradition was established.

Offenbach says his photographic project is not a straightforward study of diaspora, but rather a foray into identity – what it means to be a Jew in different parts of the world.

Keen to avoid politicising the project, he decided that the main criterion for choosing a subject should be that they self-identified as a Jew. Over the course of the four years of research, he discovered that the definition varied.

“It’s not for me to say who is and who isn’t [a Jew],” Offenbach says. “It depends entirely on who you ask. When I was in Ukraine, a man pointed at me and said that I couldn’t be a Jew because I didn’t have a beard.”

In addition to requiring people being photographed to self-identify as Jews, Offenbach needed to get a feel for their understanding of Judaism – something he encountered in Kaifeng.

“For my purpose and my book, the community in Kaifeng showed me something I was familiar with,” he says. He was taken to a “cultural centre”. In this small room Offenbach discovered a tablet with the Ten Commandments written in Chinese.

“After China opened up to tourism, a number of rabbis visited Kaifeng, keen to connect with the community and to explain more about the calendar and the Hebrew language,” he says.

This contact seems to have tailed off in recent years, but when Offenbach pressed for more details, the Kaifeng community had no complaints. They were positive about their experiences past and present.

The Kaifeng Jewish community invited Offenbach to dinner, where they served numerous Chinese dishes, washed down with local Kingstar beer, served on “Goldstar” beer mats – a famous Israeli brand of lager.

“There was no pork or shellfish served,” he says. “And I saw menorahs, seven- or eight-arm candlesticks, which are very symbolic of Jewish life, in their homes.”

The exhibition is curated with portraits grouped for maximum impact. The director of Mossad sits directly above the convicted murderer; a veiled woman, a naked life model and a fully clothed transgender waitress form a triptych. One striking pairing matches a shochet, a slaughterman, dressed in a blood-spattered leather apron with a dark-clad man – a mohel – holding a selection of tiny surgical instruments used for the ritual of circumcision.

The lack of names on the portraits is noticeable. Instead, the subjects are titled by occupation or circumstances: Refuse collector, Victim of a terror attack, Dancer.

Offenbach says he took photos of more members of the Kaifeng Jewish community but decided on using just two.

“The edit process is difficult to explain, but I felt they fit into the sequence well and I liked the result of the portraits,” he says.

“My project is about the faces. There is truth, honesty and diversity in these unretouched photographs. Each sitter is a normal person with a normal face, and I wanted to celebrate this normalcy. The ordinary is extraordinary and deserves our attention.”

The exhibition runs until April 19, 2020 at The Jewish Museum, Raymond Burton House, 129 – 131 Albert Street, London NW1 7NB (nearest tube station: Camden). Admission to the exhibition is free