Coronavirus compared to Sars, ‘Yellow Peril’ and death of Leslie Cheung in exhibition on Hong Kong’s past traumas

- Revived exhibition from 2013 evokes images of difficult periods in Hong Kong’s past, such as plague of 1894, Sars outbreak and singer Leslie Cheung’s death

- The exhibition, ‘A Journal of the Plague Year: Fear, ghosts, rebels. SARS, Leslie and the Hong Kong story’, will be a virtual one, streamed on YouTube

Viruses, plagues, racism, the emergence of local identity and the battle to retain it – Hong Kong has been here before, in 1894, long before anyone heard of severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), let alone Covid-19 coronavirus.

“Hong Kong, from the beginning of its colonial history, has always been associated with disease,” says Cosmin Costinas, executive director and curator of Para Site, a non-profit contemporary art space in the city, during a talk live streamed on April 1.

So it is apt that he, and fellow curator Inti Guerrero, should be mounting a virtual restaging of a Para Site exhibition from 2013, “A Journal of the Plague Year: Fear, ghosts, rebels. SARS, Leslie and the Hong Kong story”, by streaming videos of the artworks on YouTube.

The show addressed the outbreak of Sars in 2003, the revival of “Yellow Peril” sentiment in the West (and its historical roots), the suicide of superstar Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, and the annual pro-democracy demonstrations held in the city on the anniversary of its return to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997, after 156 years of British rule.

Presented together, the works forged a narrative between these seemingly disparate events, and today the group show resonates with what has been happening since the beginning of the year.

Like Covid-19, the outbreak of the plague in 1894 originated in mainland China and spiralled into a global pandemic that led to a highly politicised scientific debate.

Missing museums? Five amazing virtual art collections

The British explained the spread of the disease through the (now obsolete) miasma theory – that it originated in the air, caused by a rotting, poisonous vapour, which made the spread of it contingent on a place, as opposed to being spread from person to person through a contagion, which would have required a complete halt in the movement of goods and people, with economic ramifications. The profits of the British East India Company would have taken a huge hit.

A government using a pandemic to further its own agenda and hold on to power – does it ring a bell?

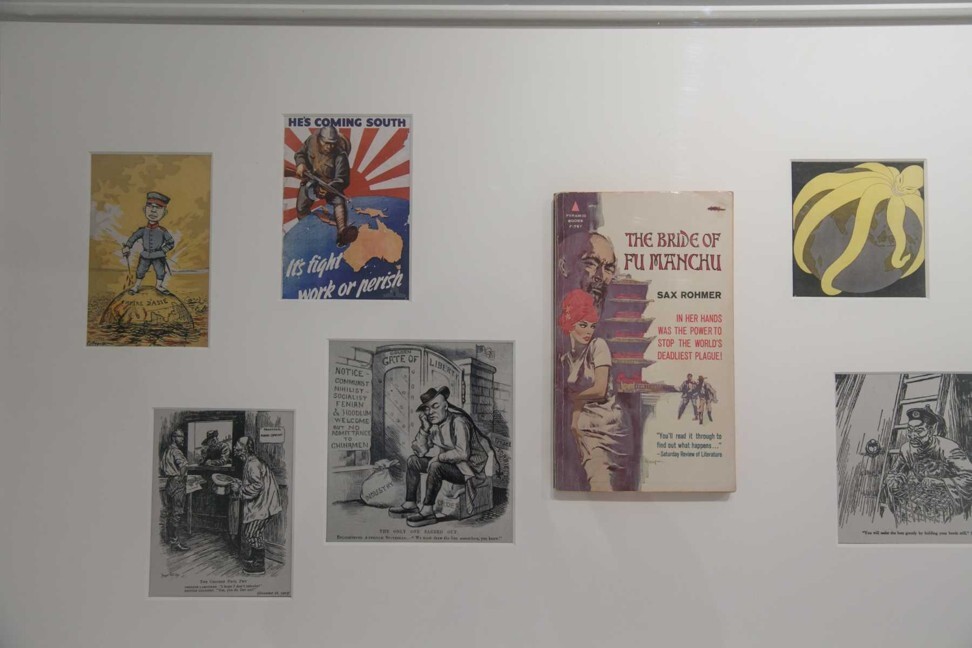

The 1894 plague led to the vilification of Asians abroad, as the exhibition recalls with its display of racist anti-Asian cartoons from newspapers of the era.

They mostly depicted and described Asians – particularly Chinese people – as being both morally and physically weak, unhealthy and unhygienic. One illustration is even titled: “You will assist the bats by holding your head still.”

Racism directed towards Asians has reared its ugly head again in the coronavirus pandemic. US President Donald Trump’s preference for use of the term “Chinese virus”, as opposed to its official name, Sars-CoV-2, served to stoke that racism.

In the decades after 1894, Hollywood took racial stereotyping a step further by making films that would portray male and female Asian characters as untrustworthy, as a number of movie posters in the Para Site show remind us.

Contemporary artist Ming Wong reclaimed this narrative in a series of photographs called China Town, based on the 1974 Roman Polanski film of the same name.

The curators of “A Journal of the Plague Year” want to emphasise the unique situation of Hong Kong and how, when most of society is brought together by a shared experience or emotion, it crystallises and reinforces the idea of a Hong Kong identity more strongly than ever before.

Cheung’s suicide on April 1, 2003, for instance, amplified the collective trauma caused by Sars, a much more deadly viral disease than Covid-19. People came out in large numbers for his funeral, despite health warnings, to pay homage to the quintessential Canto-pop star in a show of community and solidarity.

The swarms of people who showed up foreshadowed the mass demonstration on July 1, 2003, in opposition to the controversial National Security Law the Hong Kong government attempted to pass at the time.

A conceptual work by artist Pak Sheung-chuen, A Present to the Central Government (2005), addresses the significance of the annual July 1 marches. He placed pieces of cloth on the streets down which hundreds of thousands of demonstrators walked, taking imprints of their presence, then flew to Beijing with the pieces of cloth and placed them around various Chinese government buildings.

The complex relationship between Hong Kong and China resurfaced during Sars and is another focal point of the exhibition. It reveals the ambivalence Hongkongers have about their identity.

Man and Cage by artist Rick Yeung was created in 1987 before the return to China of sovereignty over Hong Kong. It alluded to Hong Kong not being consulted during Sino-British negotiations on the future of the territory.

“Building Hong Kong identity, anti-mainland sentiment, the pro-democracy movement that we’re experiencing all have a deeper history,” explains Constinas. One that, it seems, becomes increasingly visible during extraordinary times.

If you, or someone you know, are having suicidal thoughts, help is available. For Hong Kong, dial +852 2896 0000 for The Samaritans or +852 2382 0000 for Suicide Prevention Services. In the US, call The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on +1 800 273 8255.