Review | Skin whitening, the prejudice against dark skin and how class in Asia was associated with pale skin long before white colonialism

- Asian-American women explore the roots of the Asian preference for lighter skin and describe how this beauty standard affects them in a new anthology

- One contributor, of Chinese and black heritage, says her biracial background often ‘made Chinese people uncomfortable’

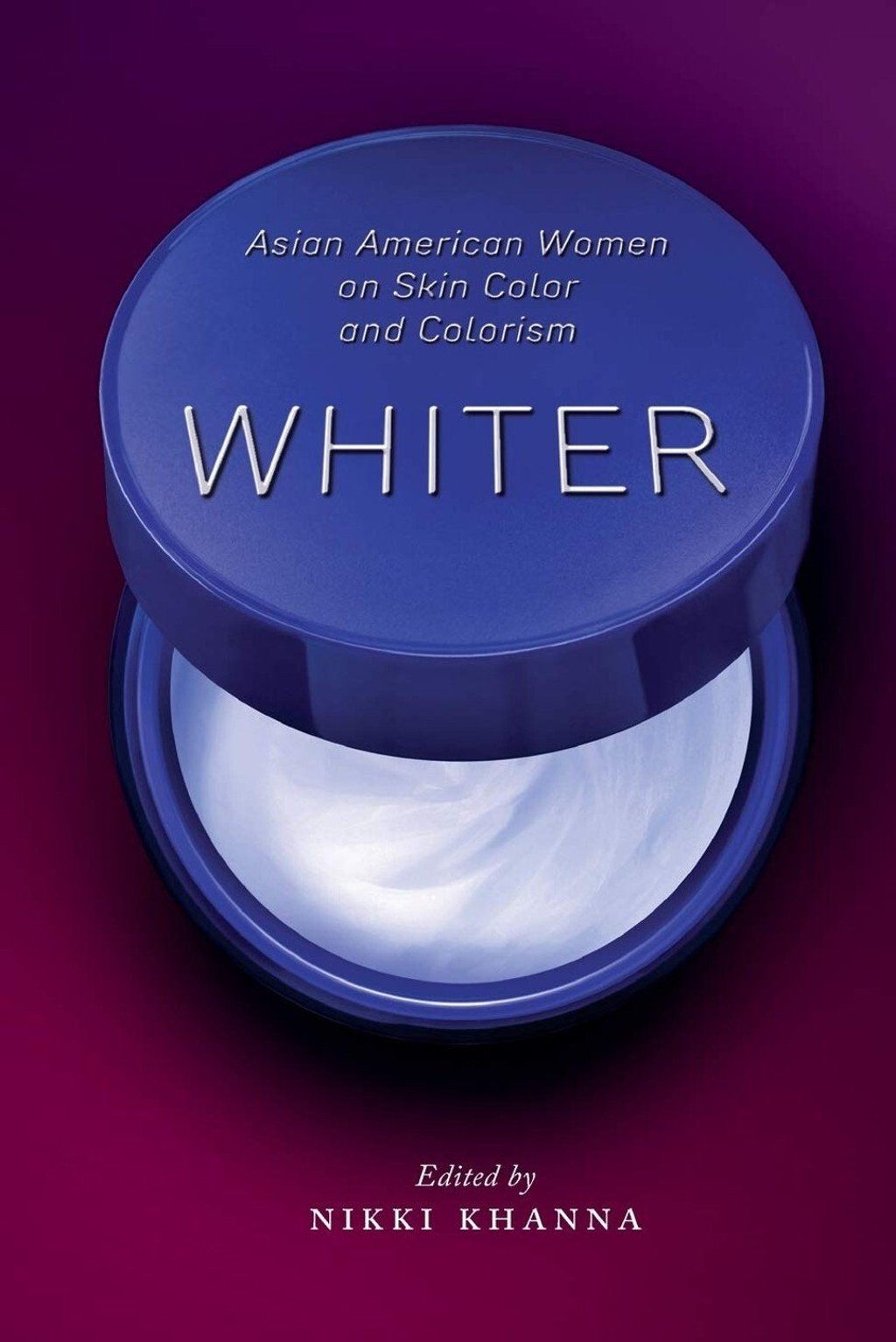

Whiter: Asian-American Women on Skin Color and Colorism, edited by Nikki Khanna, NYU Press, 3.5 stars

Pale skin is valued in Asia, where cosmetics to whiten skin are widely advertised. To many Americans, and Asian-Americans, however, the promotion of skin-whitening products appears to be racist and “colourist”.

Whiter is an anthology of essays by Asian-American women on skin colour and “colourism”, edited by Nikki Khanna, a sociologist whose previous work has focused on biracial identity.

She adopts the term colourism from American novelist and social activist Alice Walker, who first used it in 1983 to refer to the “practice of discrimination whereby light skin is privileged over dark – both between and within racial and ethnic communities”.

Khanna and her contributors also apply it to the centuries-old preference for pale skin in Asia that predates colonialism and was not connected to Western slavery. It originated in part from the association of skin colour with class, with darker skin associated with exposure to the sun during manual labour.