Review | Angkor Wat’s modern history reclaimed from French colonialists, and the cultural politics of Unesco

- The Khmer empire temples of Angkor are Cambodian, aren’t they? For decades the French considered them theirs; then came Unesco, and now China is muscling in

- Historian shows how they became a cultural-political football, abused for ‘identity construction’ by whoever was ruling Cambodia

Angkor Wat: A Transcultural History of Heritage, by Michael Falser, De Gruyter, 4/5 stars

Yet Michael Falser still finds a lot to say in his recent book, Angkor Wat: A Transcultural History of Heritage, by focusing on the modern history of the Angkor complex, with the objective of dismantling European narratives of cultural-heritage making that date from the 19th century.

Heritage is never divorced from politics and is therefore a complex and sensitive topic, one which raises critical questions about the cultural politics of Unesco and other specialised agencies, particularly in developing countries.

Falser’s two-volume book offers not only a history of the Angkor archaeological site in the context of French intervention in Cambodia, but also a critical reflection on the practices of European-derived heritage making and their application in the present day.

This voluminous publication covers 150 years of Angkor’s history, from 1860 to 2010. There are many ups and downs as the regimes ruling Cambodia change, from a proto-colonial one to direct French colonial rule, difficult diplomatic moments during the second world war with Cambodia under Japanese occupation and, finally, those of postcolonial independent Cambodia.

How lives are changing in Cambodia’s capital revealed – by bike

Falser critically deals with Angkor Wat as a product of “transcultural entanglement”: its history since the French colonisation of Indochina is layered with encounters between French ethnographers, archaeologists, museum directors and later people from Unesco. For the most part, Falser writes, they framed their heritage claims over Angkor as “international help”.

In the first volume, the author takes the reader back to 1860, when Angkor Wat was “discovered” by French ethnographers and archaeologists who, along with their successors, promoted it as a sort of French cultural heritage.

Falser traces the Angkor temples’ global journey, with objects found and taken from their sites to Paris, displayed in French museums or at exhibitions, such as the Universal Expositions in Paris (1867 and 1889), and elsewhere until 1922. Furthermore, as an archaeological site, Angkor was promoted and claimed as a French cultural possession.

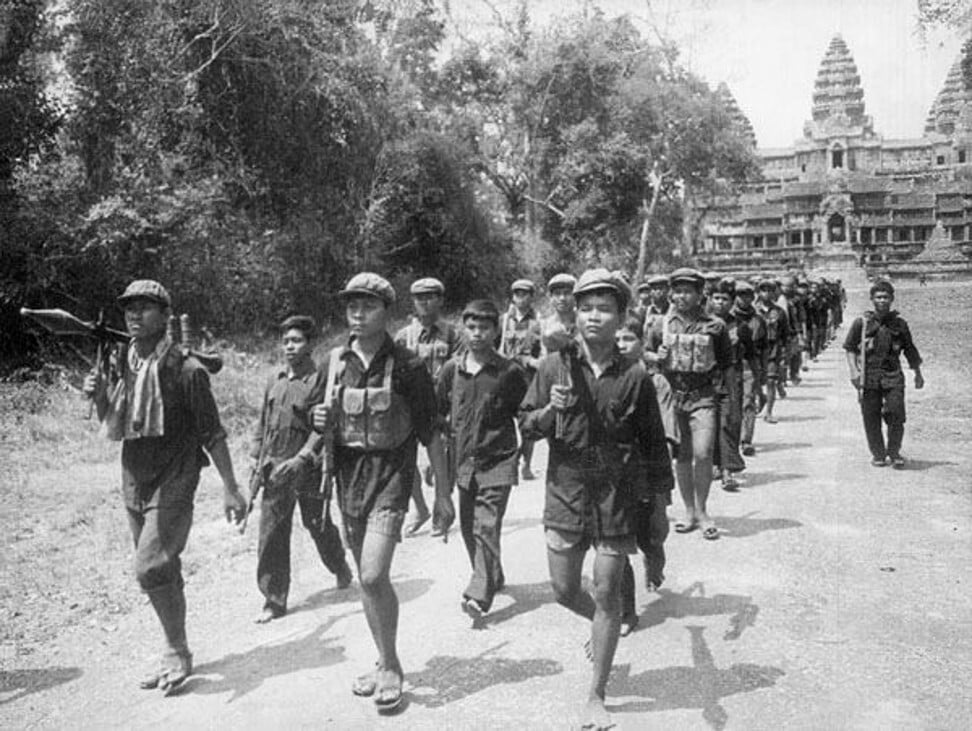

He convincingly describes the deliberate and complex strategy through which the French appropriated Angkor Wat culturally, mentally and materially. The French involvement at Angkor was only interrupted when the Khmer Rouge took over the country in 1975, and resumed soon thereafter, continuing until the present day.

As is often the case when dealing with French “colonial heritage” in the former colonies, there is only a one-dimensional narrative emanating from the French colonial apparatus. Falser supplants the mainstream narrative which mostly highlighted the accomplishments of French ethnographers and archaeologists in restoring Angkor Wat from a “ruin in the jungle” to its supposed “ancient glory”.

He also highlights the ways local actors engage with the concept of heritage and how they can debate the question on their own terms.

The second volume sets Angkor Wat as an object of contention in the geopolitical conflict between East and West in Southeast Asia and further explores its transformation from French cultural heritage to Cambodian national symbol and, later, fiercely contested global icon.

According to Falser’s research, the modern history of Angkor was constantly not so much used as abused “for identity construction by the actual ruling powers” since the French entered Cambodia and especially between 1979 and 1989. Falser clearly demonstrates that Angkor became a cultural-political symbol of Cambodian national identity and the subject of geopolitical tension during the cold war.

It is astonishing that Cambodia’s relationship to Angkor during this period has been so little discussed in scientific publications, to say nothing of a more general context. The chronological approach of the book – which is admittedly academic and densely footnoted and referenced – also makes it comprehensive for non-specialists.

A visual feast for the general reader as well as specialists comes in the shape of approximately 1,400 historic photographs, architectural plans and samples of public media, carefully selected from national and private archives in France and Cambodia, and interwoven with photographs taken by the author during fieldwork in 2010.

Falser’s two-volume book on Angkor Wat is not only a European addition to the modern history of the temple complex – the author is very aware of where he comes from – but also reveals the battles between the different who have claimed possession of the “City Temple”.

In light of the recent Chinese investment in Siem Reap, gateway to the Angkor Archaeological Park, which is now being boosted by the Belt and Road initiative to link economies into a China-centred trading network, it seems this battle is not over yet.

Asian Review of Books