Review | The Hong Kong governor who gave locals a voice, and Hennessy Road his name

- A man ahead of his time, John Pope Hennessy launched a raft of reforms after arriving in Hong Kong in 1877 and seeing how poorly locals were treated

- His consistent sympathy for the colony’s Chinese residents often riled long-established British officials, according to a new book on his life

A Stormy Petrel: The Life and Times of John Pope Hennessy, by P. Kevin MacKeown. Published by City University of Hong Kong Press

Of the 28 British governors who oversaw Hong Kong from 1842 to 1997, only Hongkongers of a certain age will have a living memory of any of them.

But of the remaining 24 colonial governors, most Hongkongers can only vaguely recall their existence by various street names: Nathan Road, Hennessy Road, Bonham Strand and so on.

This is a shame because several of these men have remarkable stories, in particular John Pope Hennessy, an Irishman who managed the territory from 1877 till 1882. The recent book A Stormy Petrel: The Life and Times of John Pope Hennessy makes an excellent case for why Hennessy should be better known, especially in these troubling times.

Author P. Kevin MacKeown is perhaps the ideal writer to have penned this richly detailed profile of Hennessy. Irish-born himself, MacKeown has lived in Hong Kong for nearly 50 years, having an academic career in research and teaching physics, including more than 30 years at the University of Hong Kong, where he remains an honorary professor. And like Hennessy, MacKeown has worked in such far-flung outposts as Bombay, Baton Rouge and Bolivia.

The 473-page book took a decade to research and is a carefully nuanced work about the complex man that Hennessy was. An intriguingly prickly protagonist, Hennessy is easy to admire, yet also easy to dislike, and MacKeown never lets him off the hook whenever his ego sprouts out of control, or some of his less thoughtful policies go off the rails. The writing is elegant and peppered with subtle but biting wit about Hennessy’s artful shenanigans.

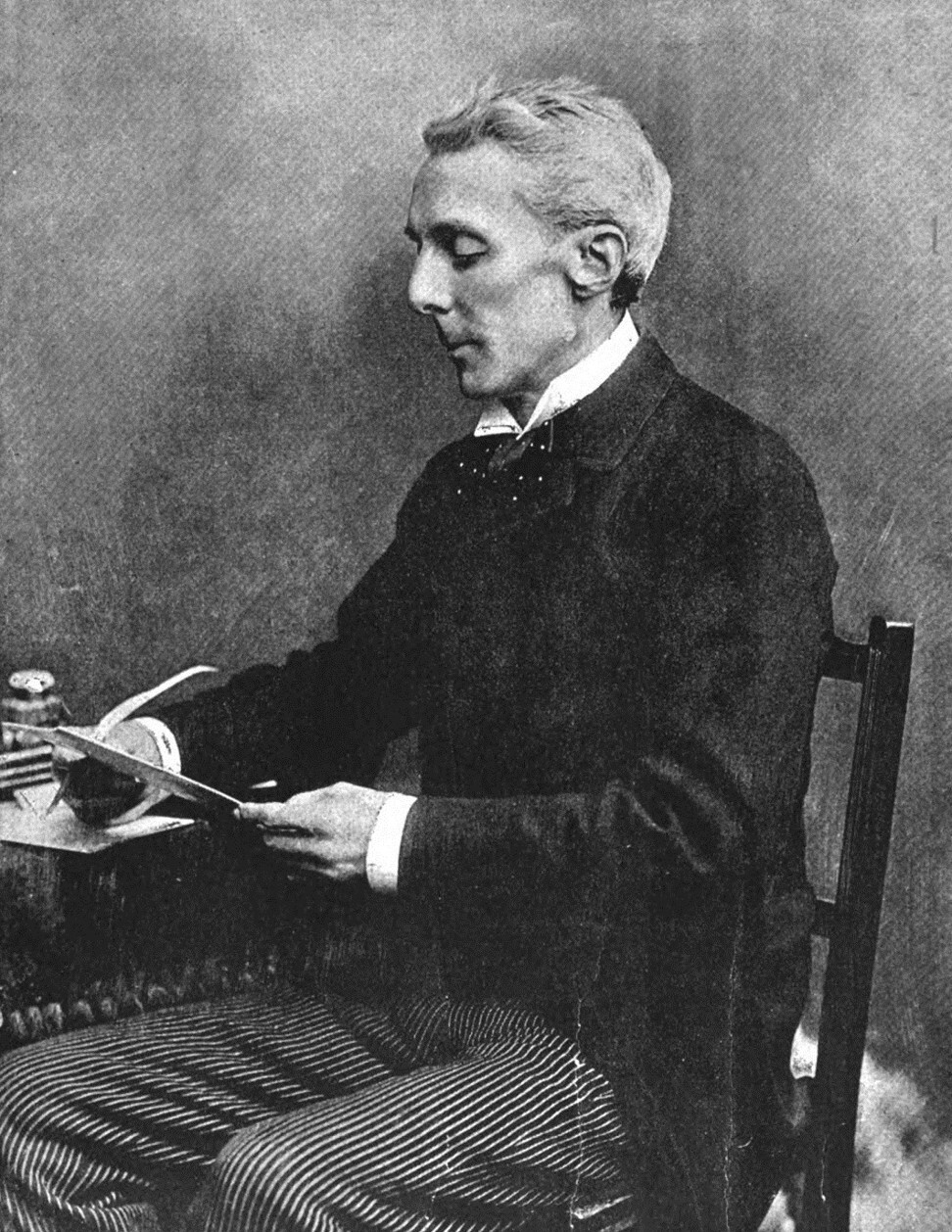

Even as a minor conservative member of parliament from Cork, Ireland, Hennessy’s ambitions were stunning. He was highly articulate, especially when talking himself up to his superiors. He was both physically and morally courageous, and could be effortlessly charming, but he was also notoriously thin-skinned and relentlessly argumentative. His personal motto for success was threefold: “The first is audacity, the second is audacity, and the third is audacity.” Early opponents referred to him as “a mick on the make”.

When Hennessy arrived as Hong Kong’s eighth governor at the age of 43, he was the youngest to have held the position. London had already posted him to a host of far less impressive imperial posts, including tiny Labuan Island off the remote coast of Borneo, West Africa’s malaria-ridden Sierra Leone (where his first child died of dysentery), the Bahamas and Barbados.

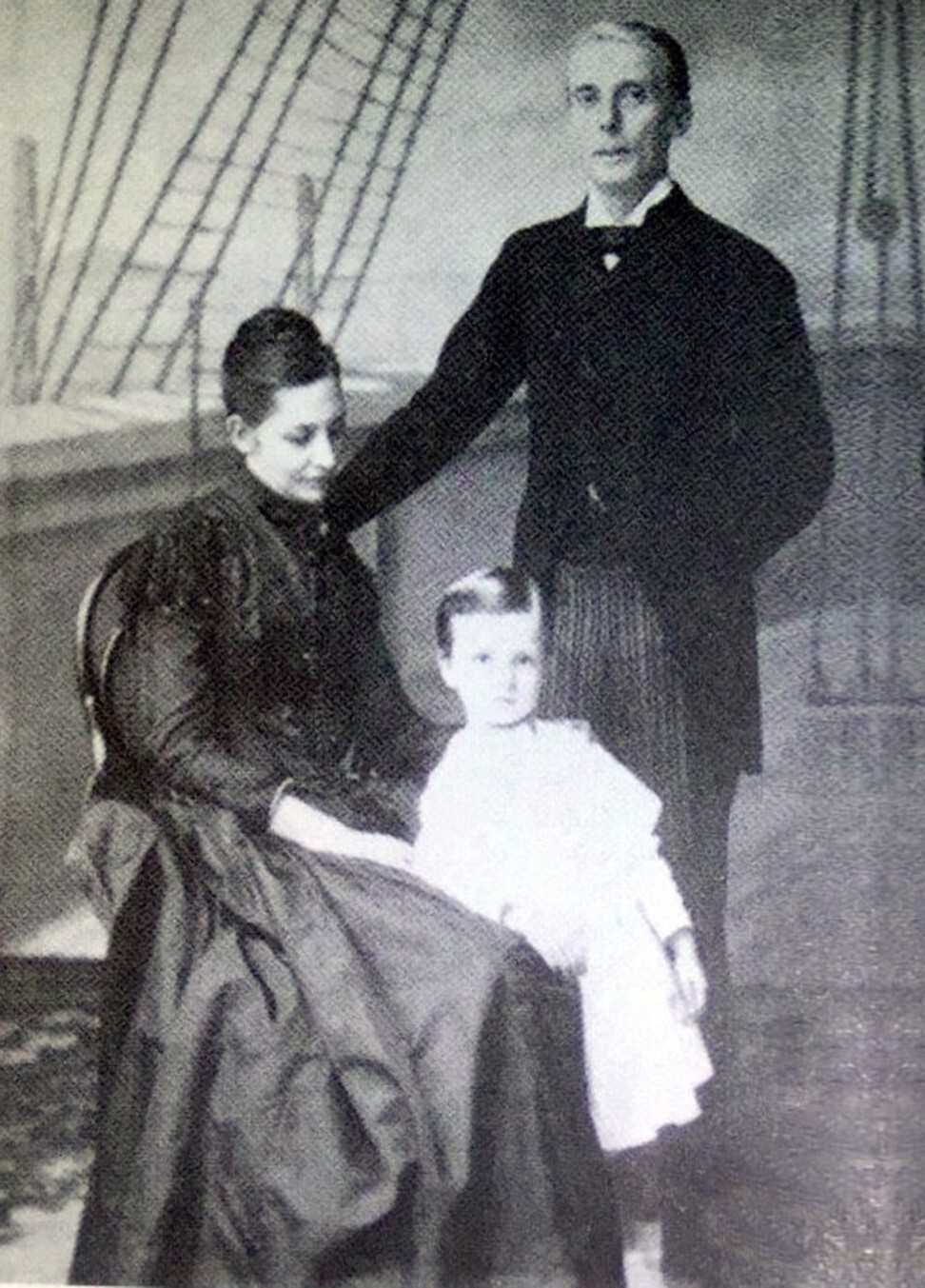

Yet even before his arrival, the long-entrenched colonial British elites disliked Hennessy, knowing that he was both Irish-born and a devout Catholic. They were also not impressed that Hennessy’s young wife Kitty was Eurasian, the child of a British father and Malay mother. Mixed marriages for chief colonial officers were almost unheard of at that time.

But the local officials soon grew to distrust Hennessy even more. Seeing how poorly the colony’s Chinese residents were treated, Hennessy brusquely launched a raft of provocative, even revolutionary, reforms: social, commercial and political.

A forward-thinking man who was often dangerously ahead of his time, Hennessy announced that local Chinese would be consulted on all matters that concerned them soon after arriving at Government House. He lifted the ban on Chinese buying land in Central district, and on even operating businesses there. Unsurprisingly, this swiftly led to a commercial boom. He appointed the first Chinese member to the Legislative Council, and allowed immigrants from mainland China to become naturalised British Hong Kong subjects.

Hennessy also brought serious reforms to Hong Kong’s shockingly primitive prison system, including outlawing both branding and flogging. “These modes of punishment,” the author writes, “under the influence of enlightenment parliamentarians, had been largely abandoned in the United Kingdom, but were still standard practice in Hong Kong.” Hennessy also halted the deportation of Chinese criminals to Australia, where the only purpose seemed to be to supply Australia with free labour.

But not all his prison reform ideas succeeded. Hennessy created a “Prisoner’s Aid Association”, the aim being to provide support for newly released prisoners. The concept of rehabilitating criminals so they could back into society as productive citizens was a century ahead of its time, even in the so-called liberal West. But the Chinese community was no more interested in helping ex-convicts than Western residents were.

Hennessy also took on controversial issues such as slavery (a murky term in Chinese society of the 1870s), opium sales, hygiene and higher educational standards. He was even an early environmentalist, launching a tree-planting blitz that saw some 750,000 trees planted annually.

Hennessy’s consistent sympathy for the colony’s Chinese residents often riled London. In an internal memo, the then-colonial secretary, Lord Kimberley, wrote: “It is quite right and politic to give some weight to claims of the Chinese in a share of the administration, but we must be on our guard against Sir P Hennessy’s ‘Chinomania’.”

MacKeown finds that wherever Hennessy was posted he upset the expatriate authorities by championing the locals. But he also did himself no favours by often publicly speaking about “home rule” for his native Ireland – the very idea of which was, of course, against the entire purpose of British Empire itself.