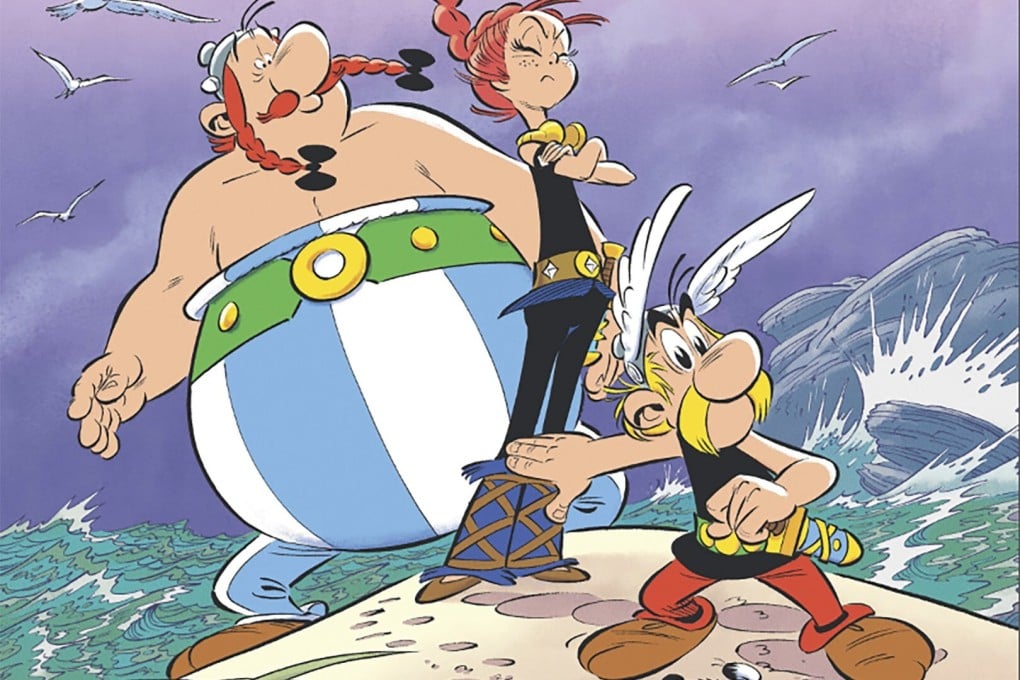

Can Asterix conquer America? French comic books about heroic Gaul get new translation to win fans in the US

- US publisher Papercutz commissions a new translation of the comic book series about heroic Asterix the Gaul, one of France’s biggest cultural exports

- The books contain slapstick for kids and parody for adults, with characters that take off stars such as Sean Connery and Elvis Presley

Americans have long adored things from France, like its bread, cheese and wine. But they’ve been stubbornly resistant to one of the biggest French exports: Asterix.

The bite-sized, brawling hero of a series of treasured comic books is as invisible in America as the Eurovision Song Contest is big in Europe. One US publisher hopes to change that.

Papercutz, which specialises in graphic novels for all ages, is republishing Asterix collections this summer with a new English translation – one specifically geared to American readers.

“Compared to the great success it is worldwide, we have a lot of potential here to explore,” says Terry Nantier, chief executive and publisher of Papercutz, who spent his teenage years in France. “We’re just looking to make this as appealing to an American audience as possible.”

Enter Joe Johnson, a professor of French and Spanish at Clayton State University in Georgia, who has translated hundreds of graphic novels and comics. He ignored the existing translation for the UK and went directly to the original French source.