Advertisement

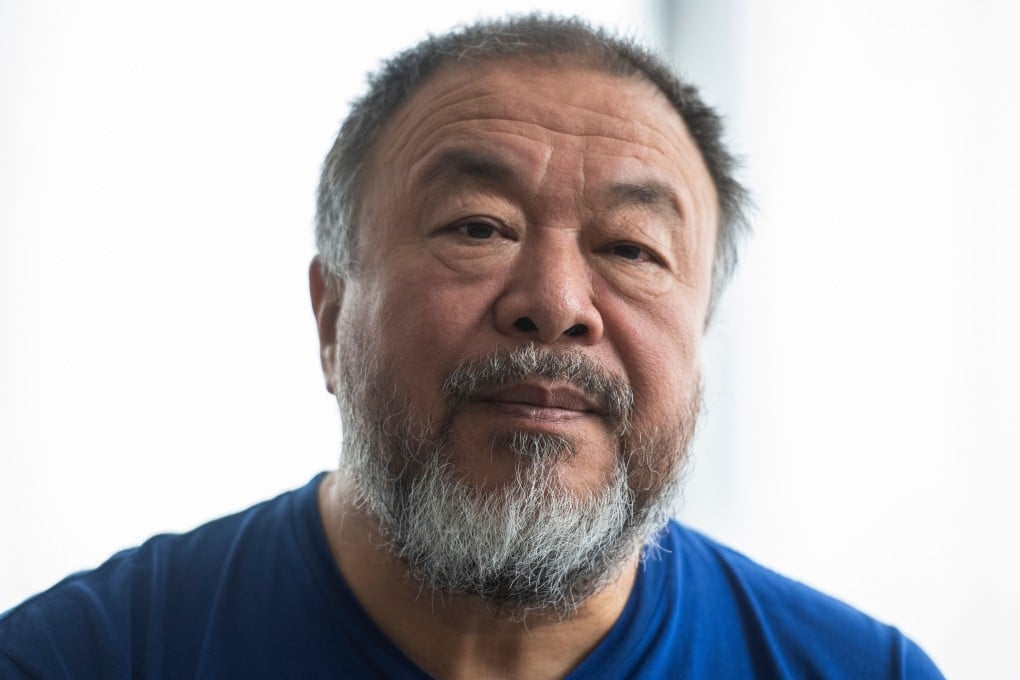

Ai Weiwei on living in exile, his artistic reaction to coronavirus and making a secret Wuhan film

- Chinese artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei talks about the world’s current state as a new documentary on his life and work is released this month

- He reveals he has three films out soon on the Hong Kong protests, the pandemic in Wuhan and Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Ai Weiwei’s mother is visibly pained recalling her son’s life as a newborn.

“He was born at his father’s darkest time,” says Gao Ying in the new documentary, Ai Weiwei: Yours Truly, released earlier this month from First Run Features.

The film, directed by Cheryl Haines, co-directed by Gina Leibrecht and available to stream through select cinema websites in the US, explores the Chinese artist and human rights activist’s 2014 public art intervention, @Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz. And it has much to say about prisoners of conscience and the role of art in both promoting freedom of expression and providing salve to the wrongfully incarcerated.

Advertisement

But it also offers a rare and captivating window into the artist’s early years, growing up in exile on the edge of China’s Gobi Desert.

Advertisement

In 1957, Ai’s father, the poet Ai Qing, was banished to a forced labour camp by the Chinese Communist government, Ai’s mother explains. She followed, the infant Ai cradled in her arms, his siblings in tow.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x