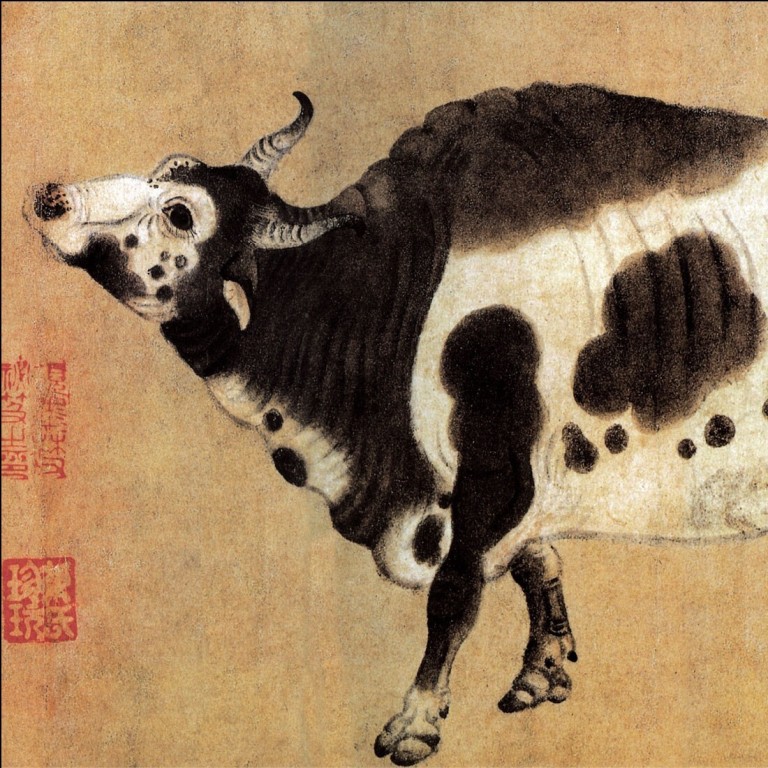

Hong Kong Palace Museum hints at content of its first exhibitions by posting image of painting Five Oxen, a grade 1 Chinese national treasure

- Museum’s director stresses it won’t house touring exhibitions from Beijing, but pick from its collection and show works in a way Hong Kong people can relate to

- Art history experts voice hope for museum and stress the importance of its values, which Ng sums up as having a global perspective on Chinese cultural history

The Hong Kong Palace Museum (HKPM) is keeping quiet about the precise content of its opening exhibitions. But this week, the appearance of an image on its website has raised hopes that its namesake in Beijing will allow some of its best-known pieces to travel to the new institution when it opens in June 2022.

Five Oxen, owned by The Palace Museum in Beijing, is believed to be the earliest surviving paper painting in China and is traditionally attributed to the Tan -dynasty politician and painter Han Huang (723-787).

The HKPM refuses to say whether the painting is coming to Hong Kong, and says merely that the “grade 1” national treasure and other art it is using for publicity purposes, such as an early equestrian portrait of Qing Emperor Qianlong by Giuseppe Castiglione, are indicative of “the types and quality” of the 800 exhibits it will borrow from Beijing.

The HKPM has no collection of its own, nor any money to acquire one. A donation policy is being drafted so it can vet gifts in the future. Talks are also under way for collaboration with international museums.

However, loans from The Palace Museum will always account for around two-thirds of its exhibits and most will never have left the Forbidden City before, an indication of the special relationship between the two bodies, HKPM director Louis Ng Chi-wa says. It is this relationship that muddles public perception of its identity.

In 2016, when Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor – at the time chief secretary for administration in Hong Kong and now its head as chief executive – revealed plans for HKPM to the board of the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority and the general public as a fait accompli, the then chief executive Leung Chun-ying, hailed it as a gift from the central government in Beijing.

Exhibitions in public museums in China often promote Chinese exceptionalism and have overt propagandistic purposes, as shown by last year’s rare public showing of Five Oxen at Beijing’s National Museum of China. The museum described the recovery of the painting from Hong Kong as “a unique side story that can tell the rising of the Chinese nation, the historical process of how it has become wealthy and strong, and strongly expresses the spirit of patriotism”.

Pressure grows on Western museums to return stolen artefacts

“We are not a satellite museum. We are not going to be showing touring exhibitions from the Palace Museum. Our own team will decide how we tell a good story about the pieces in a way Hong Kong people can relate to,” Ng says.

Ng, previously the deputy director of the Hong Kong government’s Leisure and Cultural Services Department, says the HKPM is apolitical and its curators, led by deputy director Daisy Yiyou Wang, have carte blanche access to the Beijing collection and freedom to design exhibitions the way they want.

The 800 pieces her team have selected will fill seven of the nine galleries of the museum, which was designed by Hong Kong architect Rocco Yim and has 7,800 square metres (84,000 square feet) of exhibition space.

On a display board shown during a press tour last week, the Five Oxen appeared next to the description for an exhibition titled “The Making of Masterpieces: Treasures of Painting and Calligraphy from the Palace Museum”. Other exhibitions will include two themed around the art of horses and portraits of emperors and empresses – either could feature Castiglione’s monumental portrait of The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armour on Horseback (1739), an image of which the museum’s publicity team sent out last week.

China-born Wang, who has a PhD in art history from Ohio University in the United States and has worked for many years at museums there, says the museum’s cosmopolitan team will bring a broad perspective to its programming and research projects.

Professor Yeewan Koon, chair of the art history department at the University of Hong Kong, has hopes for HKPM. “I hope it will nurture the research of Chinese art history – one that raises the bar of intellectual engagement. I think too often museums, in wanting to be popular, flatten out our histories into sound bites that create stereotypes of the past.”

Jay Xu, director and CEO of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, says all museums, HKPM included, must ask hard questions about what their own values mean to the public. The AAM has just removed the bust of its founder donor Avery Brundage and distanced itself from his racist, sexist and anti-Semitic comments. “It is work that has only just began, but if we have all learned anything from this moment, it is that values matter,” Xu says.

Just what are the values behind the HKPM?

“We want to bring a modern perspective and a global context to the study of Chinese cultural history. We want to conduct research and shape exhibitions with international partners. And yes, we will partner with the National Palace Museum in Taipei if we can reach an agreement. We don’t consider politics,” Ng says.