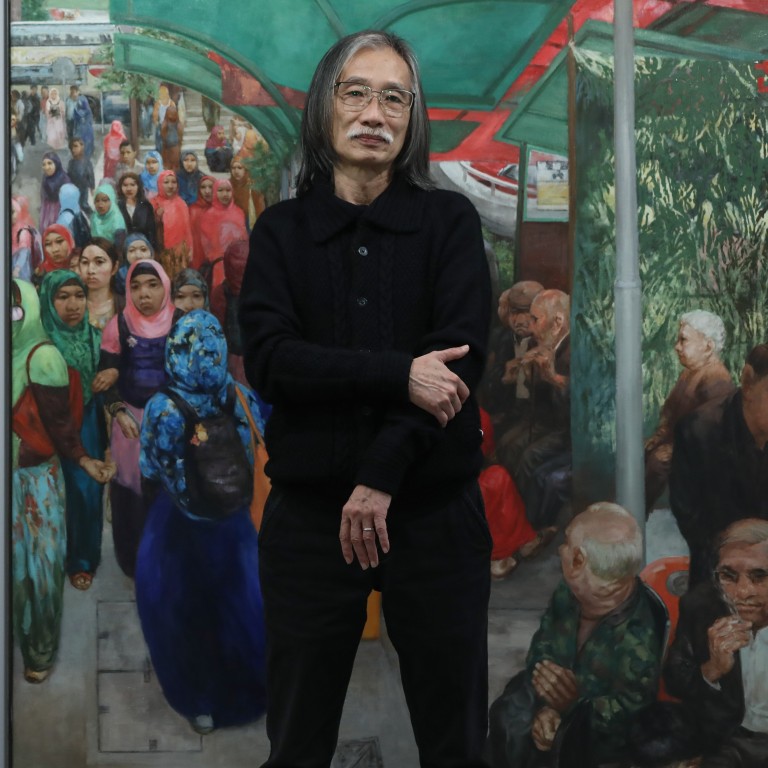

Artist best known for realistic portrayals of Hong Kong says new paintings are all illusions

- Yeung Tong-lung’s unique mixture of humour and historical references gives us a Hong Kong that is both familiar and strange

- A solo exhibition of Yeung’s most recent works is taking place at Blindspot Gallery in Wong Chuk Hang until March 6

Yeung Tong-lung’s Hong Kong is so familiar that it is easy to assume he paints from real life. How else could the shop interiors, the urban parks, the scaffolding with green safety nets in fast-gentrifying Kennedy Town be captured so vividly?

The degree of realism is such that the reflection of a light bulb can be seen in the gold lettering of a Lunar New Year fortune scroll in a new painting. In another work, the flock of pigeons are so lifelike they are practically flying off the canvas.

But something always seems off when it comes to his figures. Often heavily foreshortened, their disproportionately large heads, wide eyes and wooden expressions give them a tragicomic air that makes it clear they are not a cliched, mawkish celebration of the quotidian and the local.

This is made more obvious in his recent works, currently being shown at Blindspot Gallery in Wong Chuk Hang.

Yeung avoids talking about his paintings explicitly, but he is eager to dispel the notion that the scenes are “real”. These paintings are crammed full of illusions, multiple perspectives and the mingling of the real and the imagined, he says. His figurative paintings, then, are less a record of an urban landscape and more a metaphor for the subjectivity of seeing.

Take Porcelain Dog (2020) for example. In the foreground is a woman who may be a domestic helper, sitting on an outsized designer chair in what looks like a branch of Ikea. She is looking straight at the viewer who, as is usually the case with Yeung’s paintings, is made to watch from an elevated, godlike position.

Not even poor health or vision could stop these Hong Kong artists creating

With her right arm extended, she beckons the viewer to enter her world. A porcelain dog appears to be looking at its own reflection in a mirror, while two men with identical hair are facing each other, seemingly in an embrace, perhaps kissing.

Are the two men engaging in a public display of affection in the middle of a shopping trip? Or is the suggestion of intimacy simply the result of the way they happen to be standing? They may even be the same person, one the mirror image of the other.

On the left is a woman with her back turned to us who has just dropped her jacket on a bed. She is taking off her heels as if she thinks she has just got home after a tiring day in the office, rather than walked into a furniture showroom.

“There really isn’t a ‘right’ answer to these questions. It is up to the viewer to decide,” Yeung says.

Odd details abound in all his paintings, like the phone cover in the hand of the selfie-taker in Window Glasses No. 5 (2019) that seems to be a fragment of Carravagio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. They give pause and force a close reading.

There is plenty to mull over in the 4.5-metre-wide triptych called Mount Davis (2020). The side panels refer to specific chapters of Hong Kong’s history: the retreat of British soldiers from Japanese invaders during the Second World War, the temporary housing for Nationalist soldiers who came to Hong Kong after the Communists won the civil war in 1949, and the holding of political prisoners in the brutal Victoria Road detention centre after the 1967 riots.

In that scene, inexplicably, an African woman with a colourful headscarf is rinsing off the walls with a hosepipe.

She is a cleaner, judging by the reflective vest she is wearing, and her face is hidden from us, one of many nameless minorities whose stories in Hong Kong are forgotten, along with episodes of history too inconvenient or embarrassing for those in power to be recalled in a hurry.

The middle panel, a baffling non sequitur set in a bonesetter’s clinic, has intriguing visual clues tucked away, such as a small painting with the name Tsuguharu Foujita, a French-Japanese painter who became Japan’s official war painter. There is also a bundle that looks like a roast turkey, which Yeung says is the root of a plant with powerful medicinal qualities known colloquially as “golden-haired dog”.

“These, like the multiple, non-linear panels, add to the interest of the paintings, I hope,” Yeung says modestly.

Yeung’s paintings are easy-on-the-eye and accessible, and they can be described offhandedly as charming, skillful and beautiful. But this exhibition and the accompanying publications by Art and Culture Outreach reveal the depths of his historical vision, his innately humanist perspective and his great storytelling skills. This serious consideration of Yeung’s place in Hong Kong art history is a belated but welcome endeavour.

Yeung Tong-lung: Daily Practice exhibition, Blindspot Gallery, 15/F Po Chai Industrial Building, 28 Wong Chuk Hang Road, Wong Chuk Hang; Tuesday to Saturday, from 10:30am to 6:30pm. Until March 6.