Mastermind of Muji to Go line, collaborator on Shiseido eyewear, inspired by Henri Matisse to paint with drones, Dai Fujiwara is a design chameleon

- Dai Fujiwara, giant of Japanese design, has lent his creative input to companies while also pursuing personal projects such as sweaters woven from detritus

- He has embraced technology such as drones while also using watercolours to perfectly match colours in life. His first solo show in Hong Kong recently opened

In January 2018, New York street cleaners were fascinated to find Dai Fujiwara in Times Square vacuuming up garbage in the frigid cold.

“They said, ‘Dai, what are you doing?’” the Japanese design giant recalls, laughing. “I spent a week in Manhattan, cleaning up. I went to Liberty Island, Wall Street, Times Square and Broadway, and some of the parks. The cleaners were really interested in the handheld vacuum. They liked it very much.”

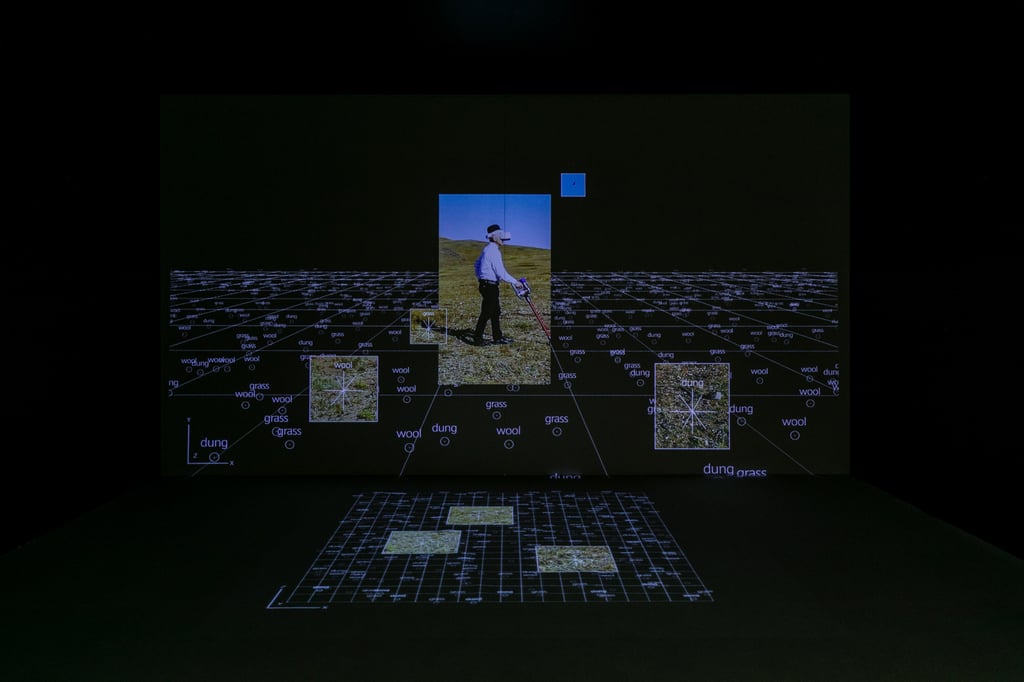

Fujiwara repeated the exercise in the Japanese capital, Tokyo, and on the Mongolian steppe, where he collected hair from yaks, sheep and cashmere goats. The detritus was then spun into yarn. Four “Grassland Sweaters” and four “Urban Sweaters” are the result.

For that project Fujiwara focused on the question of waste and the future of the fashion industry and fast fashion. Was it possible to make garments from garbage? Will robots someday be gathering wool?

His findings form part of an exhibition at the Hong Kong Design Institute in Tseung Kwan O titled “Dai Fujiwara: The Road of My Cyber Physical Hands”, which explores technology and the human touch in his art and design.