Why design couple value vernacular architecture, their ‘surgical’ adaptation of old buildings in China and elsewhere, and the ideas that underpin it

- Lyndon Neri and Rossana Hu founded architecture practice Neri&Hu in 2004 in Shanghai, where they were shocked to see how disposable old buildings had become

- Their appreciation of the value of vernacular architecture, and work that connects the old and the new, is explained in their latest book

Lyndon Neri and Rossana Hu, the duo behind Neri&Hu, published their first book four years ago. It documented the first 10 years of their architectural practice, which they founded in Shanghai in 2004. “But it was kind of anticlimactic,” says Neri.

A publication delay meant that it had already missed several years of evolution in the duo’s work by the time it came out. It also missed a pivotal moment in China, which had developed an appetite for thoughtful, sophisticated architecture after years of rampant economic growth.

And so the architects got to work on a new book, Thresholds: Time, Space and Practice (Thames and Hudson). It is an ambitious attempt to capture the intellectual currents that course through Neri &Hu’s work, which encompasses architecture, interior design, products and branding.

The book includes essays by other architects, among them Pritzker Prize winner Rafael Moneo and Harvard professor Sarah M. Whiting, who offer succinct analyses of exactly what it is that makes the Shanghai firm’s work so interesting. Whiting describes it as a “doubled blackjack bet”, combining seemingly contradictory concepts like “future artefacts” and “inhabitable strata” in spaces that raise more questions than they answer.

Most architects like the idea of tabula rasa, starting from scratch But Rossana and I do not always believe in that.

Heady stuff – but the book’s photo spreads, diagrams and illustrations make it easy to appreciate why Neri&Hu have earned international acclaim over the past 15 years.

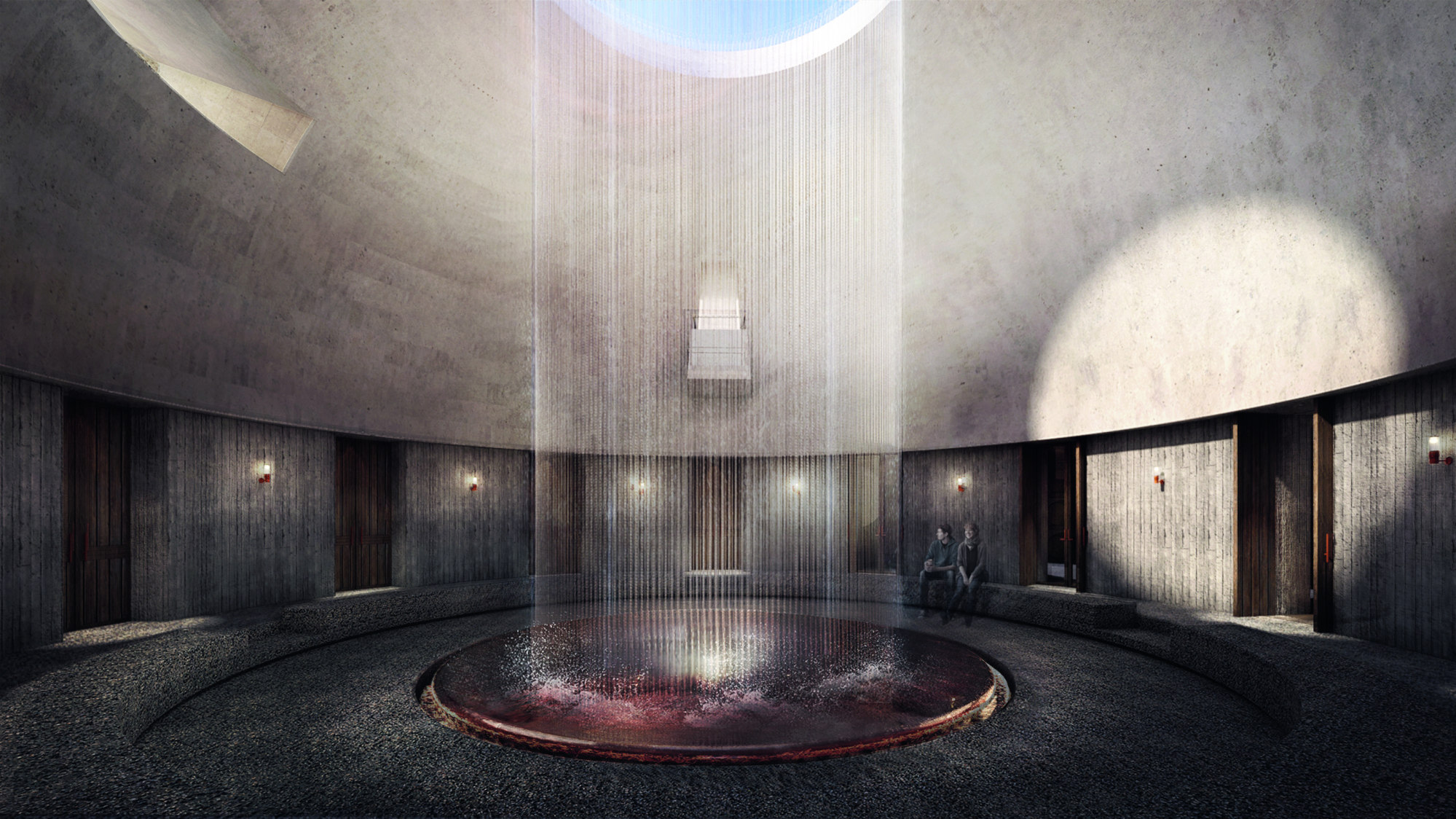

Along with dozens of small retail spaces, residences and conceptual installations, their key projects include The Waterhouse at South Bund, a boutique hotel fashioned out of a decrepit 1930s warehouse, as well as the Suzhou Chapel. From the outside, it appears to be an ethereal glass box set atop a sturdy base of local grey brick, but inside it contains a luminous wood nave that is as warm as the exterior is cool.

Most of Neri&Hu’s projects layer forms and materials in ways that feel contemporary yet rooted in local traditions. The Yangcheng Lake Villas in Suzhou offer a modernist interpretation of traditional courtyard houses, with metal screens that call to mind the bricks used in the area’s historic architecture.

A new lobby for the Shanghai Theatre – an art deco palace that had been heavily modified through piecemeal renovations – recalls the theatre’s original splendour through moody granite-coloured spaces with bronze accents.

In designing a new Shanghai campus for Swiss lift manufacturer Schindler, the architects created a massive grey brick wall whose variety of textures makes it look deceptively ancient.

Japanese architect follows in father’s footsteps by designing Olympic swimming centre

The couple explain how their work is underpinned by the interconnection of old and new, rough and smooth, transparent and opaque. “Most architects like the idea of tabula rasa, starting from scratch,” says Neri. “But Rossana and I do not always believe in that.”

When they moved to China in the early 2000s – Neri is Chinese Filipino, Hu is Taiwanese American, and both had been working in the United States – the couple were shocked by how disposable so much of the country’s built environment had become.

Entire cycles of development, abandonment and redevelopment had been compressed into just a few years. “How do you deal with abandonment in a society that deals with new, new, new?” asks Neri. “Our buildings are not about me and Rossana at all. They’re about issues of a global scale that we have to tackle.”

It comes down to a few of the ideas that Neri&Hu explore in their book – the idea of the vernacular, how to represent local culture and why architecture must accommodate the change and decay that comes from age. Hu says these are concepts that came to fruition when they began working on The Waterhouse in 2008. Although it was an old building, it wasn’t considered historically important by officials, and the client expected to demolish it. But Neri and Hu’s first site visit revealed a building rich in character, patina and quirks such as stairs to nowhere.

“We came home and said, ‘What if we try to preserve the parts we thought were interesting?’” recalls Hu. “The client was shocked.” But they successfully argued their case.

The result marked a turning point in historic conservation in Shanghai, highlighting the value of the ordinary buildings that give the city its unique feel.

Their experience with that project has informed many others since then. The Design Republic Commune in Shanghai, which houses a design hub and a flagship location of Design Republic, Neri&Hu ’s own brand of design shops, takes what the architects call a “surgical” approach to adapting a historic police headquarters in a stately Edwardian building from 1910, removing small parts of the original structure and adding sober glass and steel additions to accommodate new uses.

In the Shanghai neighbourhood of Tianzifang, the architects plugged in the vacant space between two historic town houses with a radically transparent glass facade that emphasises, by way of contrast, the architectural details of its neighbours.

Neri and Hu are fascinated by vernacular architecture – grass roots construction based on local culture, materials and building techniques – and they make an effort to ground their projects in whichever location they are being built. “It’s not just culture, it’s also a sustainable approach,” says Neri. “We use a lot of recycled materials.”

In Yangzhou, where the firm designed the Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat – which is arranged around a series of courtyards made with local brick and timber – he says they “started going around asking people for their waste – old bricks, things with different shades and materials. The material tells the story of a particular region.”

That has become a guiding principle for the practice, whose projects span the world. Although most of their work is in China, Neri and Hu have designed buildings and interiors throughout Asia, Europe, the Americas and Australia.

In Kuala Lumpur, the Alila Bangsar caps a high-rise hotel with a surprisingly intimate courtyard; in Paris, for a Japanese-Italian restaurant called Papi, the architects embraced the decay of a 19th century Haussmanian retail space, installing a cheerily curvaceous interior amid exposed stone and peeling plaster.

In one of their current projects in Merano, Italy, they are exploring the Austrian influence that pervades the surrounding region, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire for much of the 19th century. “The idea of creating vernacular is a global issue,” says Neri.

The couple and their practice have no shortage of opportunities to explore those kinds of issues. But they are choosy about what kind of projects they work on. Neri says they were approached by 500 prospective clients last year.

“We took on 12. As the practice has grown, we realised we were not so interested in the commercial aspect of architecture. We’re more interested in how culture can be represented in architecture.” There are still a lot more ideas to explore – and perhaps more books to write.