Racism against Chinese-Americans is personal for CNN’s Lisa Ling, who uses her series This is Life to explore its history

- Ling uses her CNN series to explore racism against Chinese, recalling Vincent Chin’s 1982 murder that she says ‘exacerbated that feeling of un-belonging for me’

- She includes clips of herself at a Stop Asian Hate rally in Los Angeles, and says she sees a silver lining in Asian-Americans talking to each other about racism

A television journalist in the public eye for more than 20 years, Lisa Ling was horrified by remarks she saw last year when the United States was shut down by the Covid-19 pandemic.

“The day after Donald Trump called Covid-19 the ‘China virus’ I got two messages on social media that told me my people were responsible for it,” says Ling, 48. “I saved the tweet: ‘I hope you and your kids die from the Wuhan virus.’”

The words hurt Ling, who is Chinese-American and grew up in Carmichael, a suburb of Sacramento in California and now lives in Los Angeles. When she saw how similar rhetoric led to a surge in the number of attacks on Asian-Americans in cities across the US, she was galvanised.

In the premiere episode of the eighth season of Ling’s CNN documentary series This Is Life, she takes an intensely personal look at the long and torturous history of prejudice against the Chinese community in the US.

The Legacy of Vincent Chin is the first of eight instalments that examine how today’s divisive and often intractable issues involving race, gender and equality are rooted in the past.

The retrospective approach is partly down to health protocols that kept Ling from producing the immersive, long-form storytelling of This Is Life in its first seven seasons (now available for streaming on HBO Max and YouTube TV).

A mother’s fight for justice: the killing of Vincent Chin

“Our shows are very experiential, and we had to pivot because we couldn’t do that,” Ling says. “I had this idea of being able to rely a little bit more on archival footage and not feeling like we had to be as close physically and intimately.”

The attack followed a scuffle in a nightclub where Chin was holding his bachelor party. Ebens was heard using slurs and blaming Chin, a Chinese-American draftsman who had nothing to do with the economic crisis.

Ling remembers being ten years old when her father read about the incident in the newspaper. “It just exacerbated that feeling of un-belonging for me,” she tells viewers.

Even as a popular kid growing up, Ling was teased over her ethnicity. Some classmates called her “Risa Ring”. It made her hate being Chinese-American. She never complained, repressing her feelings of shame and self-loathing.

The admissions are striking. In the past, This Is Life viewers have watched Ling glide through dangerous situations and unfamiliar worlds with confidence and a touch of bravado as she tells her stories.

“What is happening now is Asian-Americans are actually communing and talking to each other about it and realising that we’re not alone in this,” Ling says. “And that’s been, for me, a really powerful silver lining in all of this.”

A lot has changed, but in some ways this idea that Asian people have continued to be looked at as foreigners in our own home has not changed at all

Ling includes CNN clips of herself appearing at a Stop Asian Hate rally in Los Angeles. While she is not a CNN employee – her programme is supplied to the network by production company Part2 Pictures – journalists appearing at social protests have been a point of contention in some newsrooms. But Ling felt compelled to take an activist role.

“If I don’t use my platform to try and protect people, and to remind people of the fact that we are Americans and we belong here, then what good is it to have a platform?” Ling says.

“I have not enjoyed doing this. When I’ve appeared on other shows talking about this, I’m literally shaking under the table. It has consumed so much of my head space and my heart space when I see these brazen attacks of our elderly that are going viral, because that could be my grandfather or my own father.”

Amy Entelis, executive vice-president for talent and content development at CNN, supports Ling’s first-person approach to the story.

“Lisa, like all of us, was very much affected by events of the last 18 months,” Entelis says. “Sadly, there has been such a rise in anti-Asian American hate crimes. An episode from Lisa on this topic added unique depth and empathy.”

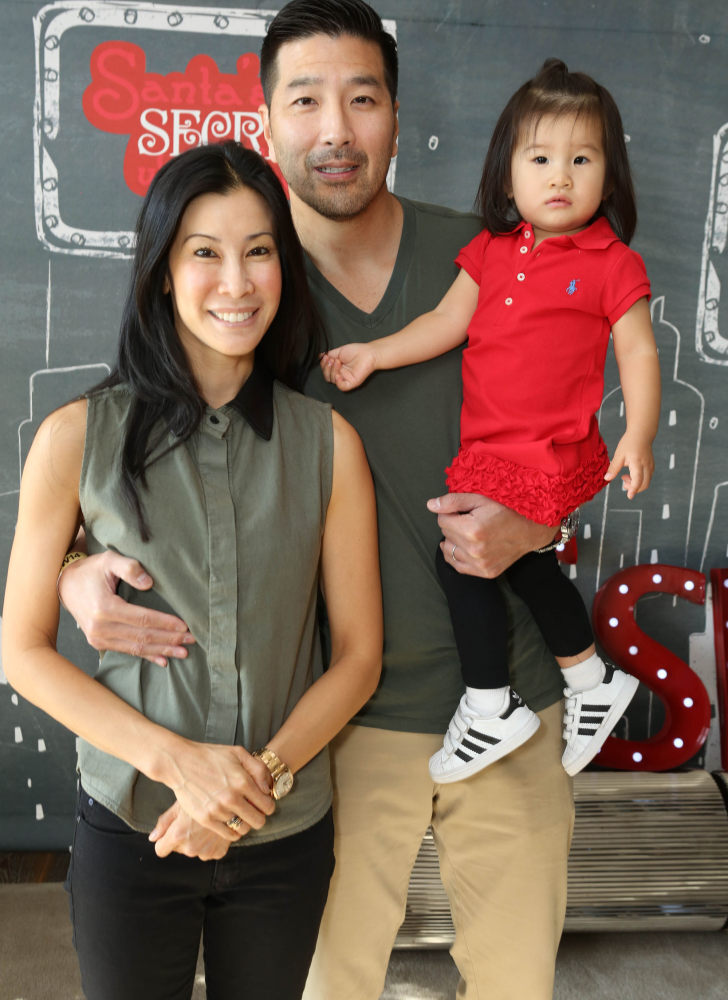

Ling has two young daughters with husband Paul Song, an oncologist. She tries to educate her daughters about discrimination, reading them books and recounting stories about the World War II internment of Japanese-Americans, the civil rights movement and slavery. But she cannot always protect them in the outside world, even at a grocery store in nearby Brentwood.

“When my eight-year-old was six, she was at a Whole Foods with my mother and inadvertently spilled a little water on a man’s shoe. And he became apoplectic and caused a scene,” Ling recalls.

“It was so traumatising for her that a manager had to tell him to leave. He waited for my mom and my daughter outside and yelled to them, ‘Go back to China’, as soon as they emerged. And my daughter was just so confused. She’s like, ‘Go back to China? Am I from China?’”

Later in the season, Ling gets a first-hand look at gang violence in Chicago, where she met her husband and once made her home. With shootings in the city up 10 per cent compared with 2020, her entry point is a 1919 incident when a black teenager was murdered after his raft drifted to an area of a Lake Michigan beach restricted to white people.

The boy’s death led to deadly riots in Chicago and set in motion the cycle of racist economic and housing policies that led to the gang violence that still plagues the city today.

“Having spent a lot of time in Chicago, it breaks my heart to read every week about all the killings there,” says Ling. “It’s so easy to discount it as gang-on-gang, black-on-black crime. But when you really dissect all of the dynamics that had been in play in the city over the last 100 years, it’s plain to see that those invisible lines – the construction and then the demolition of housing projects, and then just planting people in communities where they know no one, that already have existing issues, there’s no wonder it has erupted in this kind of violence.”

Ling also will explore the 1950s Cold War-era campaign to purge gay people from the US government, known as “the Lavender Scare”. She travels to Oklahoma to examine the “Reign of Terror” killings of Osage tribe members who flourished in the 1920s during the nation’s oil boom.

As the military’s handling of sexual harassment cases is re-examined after the 2020 murder of US Army soldier Vanessa Guillen, Ling revisits the Tailhook Scandal of 1991, when a convention of aviators ended with at least 83 individuals assaulted in one weekend.

Ling’s stories come at a time when school boards across the country are attempting to restrict teachings on the darker chapters of the country’s past, such as slavery and segregation. They are a reminder that social progress can be fragile, something Ling has been forced to contemplate herself after the last 18 months.

“In this century, there have been moments where I’ve thought that Asians were really starting to gain traction,” Ling says.

“In the last couple of years some incredible blockbuster movies came out featuring Asian casts. And then Covid-19 struck and it forced so many of us to really reckon with this country’s history and our sense of belonging here.

“A lot has changed, but in some ways this idea that Asian people have continued to be looked at as foreigners in our own home has not changed at all.”