Advertisement

Business of Design Week 2021 in Hong Kong to focus on a ‘design reset’, with two Chinese architects bringing ‘human survival wisdom’ messages

- The theme of this year’s Business of Design Week is ‘Global Design Reset’. Among its speakers are two architects forging a path towards a sustainable future

- Of importance to Beijing-based architects Zhu Pei and Luo Yujie is the idea of regional culture, which sees new buildings fit in with and reflect their locality

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Around the world, humanity is undertaking its greatest migration of all time – from countryside to city.

This movement of people accelerated in mainland China after Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 reforms, and has created vast conurbations bustling with commerce and peppered with extravagant contemporary architecture, while villages continue to be drained of the young and able.

Among other things, the growth of cities drives climate change. The World Green Building Council estimates that buildings alone are responsible for 39 per cent of carbon emissions, including 11 per cent in their construction.

Advertisement

In architecture, it seems that we need a “global design reset”, which happens to be the theme of this year’s Business of Design Week (BODW), taking place from November 29 to December 4 and organised by the Hong Kong Design Centre. Among its speakers are two Beijing-based architects who have been forging a path towards a sustainable future.

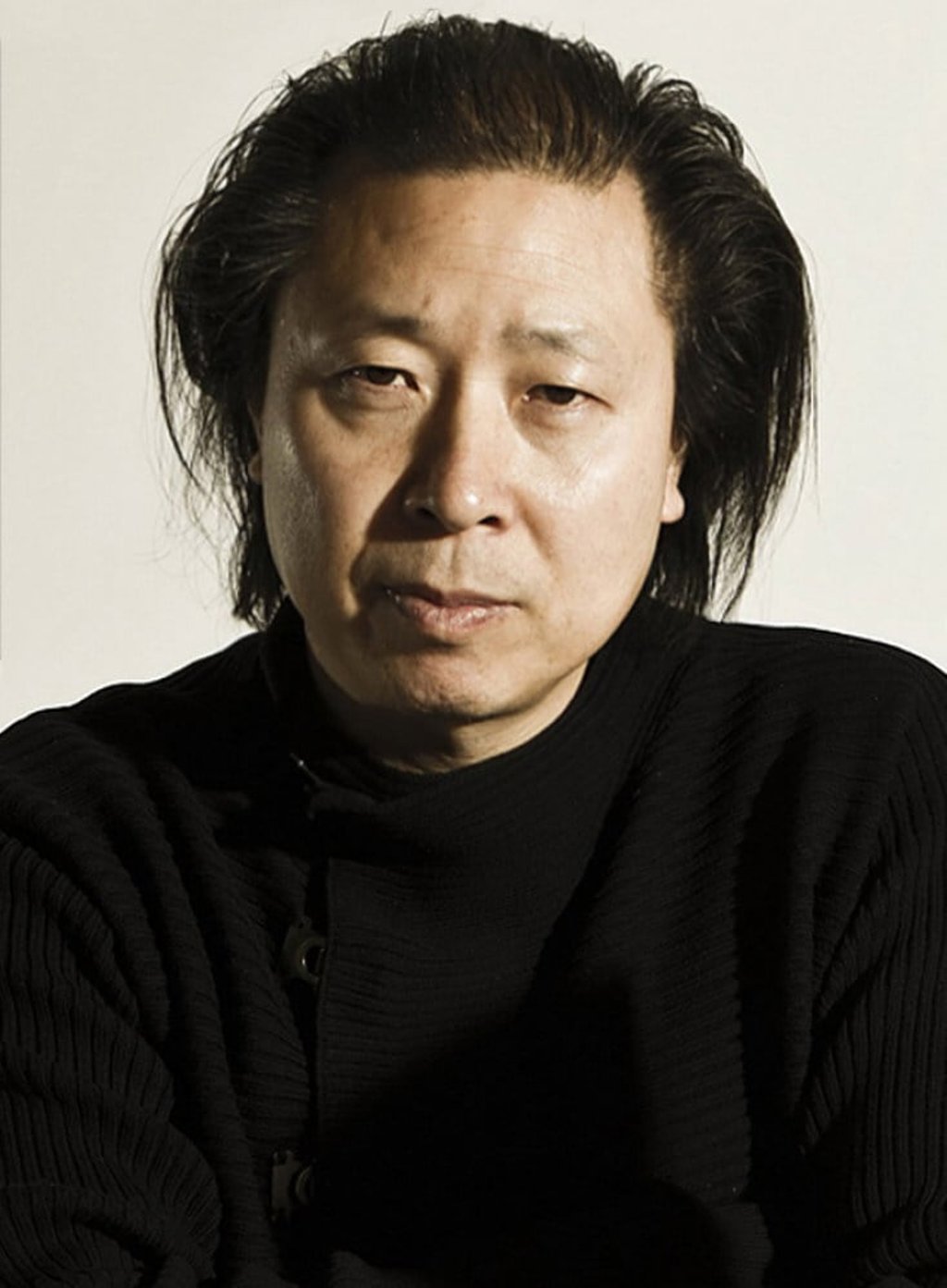

One is Zhu Pei, founding partner of Studio Zhu Pei and known for a string of extraordinary cultural venues across the country. For him a reset is not enough. “We should address the public [to say] our cities and buildings are crime culprits for increasing climate change,” he says.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x