Neon artist Karen Chan reclaims a Hong Kong icon and forges her own path as a woman in a traditionally male craft

- Karen Chan, the only active female neon light maker in Hong Kong, is part of a movement out to revive use of a material that defined the look of the city

- She explains how tough it is to mould the glass tubing that goes into neon and plans to discuss her work in a male-dominated industry at a TedXTinHauWomen event

Karen Chan’s design studio in Fo Tan, in Hong Kong’s New Territories, oozes creativity. A huge, lightsabre-wielding figure of Darth Vader, the lead villain in the Star Wars films, dominates one shelf, and others are lined with retro cameras and film equipment.

“A lot of these items were given to me by my dad who worked in the post-production industry,” Chan says.

The space is also alive with neon.

Chan is the only active female neon light designer and maker in Hong Kong. The 33-year-old is part of a small but passionate movement determined to revive the use of neon in art, commercial spaces and signage – efforts that are sorely needed to keep an icon of 20th century Hong Kong in the public eye.

Backdrops drenched in neon became synonymous with how Hong Kong was seen in popular culture, from Ridley Scott’s 1982 science fiction film Blade Runner, inspired by the city’s streetscapes, to Wong Kar-wai’s 1994 movie Chungking Express.

Chan makes a great ambassador for the trade because she is well versed in international design practices: as well as her background in set design and visual merchandising, she holds a master’s degree in design and technology from New York’s Parsons School of Design.

“I was abroad [in London, New York, Paris and the Netherlands] for more than 10 years, and it was only then that I started to miss the visual cues of my city like pawnshops and neon signs,” she says.

Back on home turf, Chan was determined to pave her own creative path “and avoid a corporate one”. A chance meeting in 2018 with 70-year-old Hong Kong neon master Wong Kin-wah, affectionately called Uncle Wah, allowed her to do that. Wong shared the secrets of his trade with Chan. Now she wants to share them with others.

“In Hong Kong, neon making is still seen as a secret trade but in other parts of the world it has opened up, with academic schools and workshops,” says Chan (also known as Chankalun), the creative director of art design studio CeeKayEllo and also the founder of HKCrafts, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that promotes and preserves Hong Kong culture and heritage. “I want that to happen here.”

She also has connections with Tetra Neon Exchange, a Hong Kong NGO dedicated to conserving neon, to try to move neon-making forward and give it a modern twist. She also wants greater respect for the original neon crafters who helped forge the city’s iconic streetscapes.

The art of neon bending – the process of hand-shaping glass tubes over an open flame – is hard work.

“Neon bending should be an Olympic sport,” laughs Chan. “Like weightlifting, it needs strong arms and fingers to hold the heavy tangled glass tubes, it needs concentration and accuracy like archery, and requires quick and strong reaction with flexibility like gymnastics.”

She says a neon-bending studio tends to be noisy and very hot. “One time I puked in Master Wong’s studio because I got heatstroke from bending neon, even with the AC on,” she confesses.

Being a woman doesn’t put her at a disadvantage, though. “We all come in different shapes and forms. It’s about how we accept them and make them work to our advantage,” Chan says.

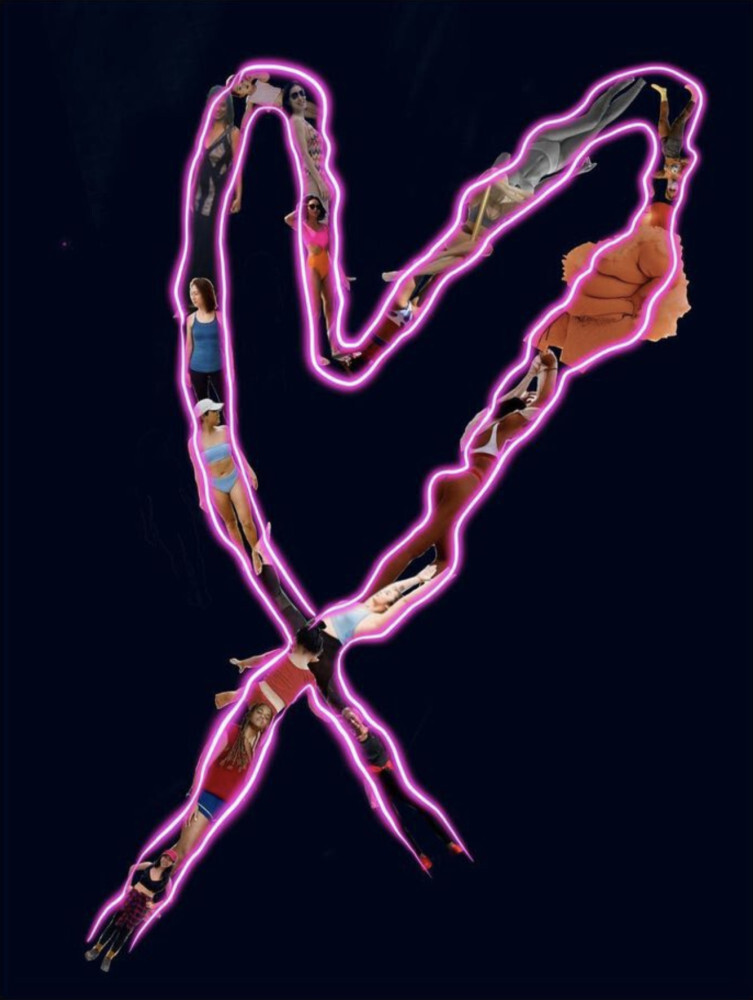

“The piece is about self-love and how we should embrace our body shape,” Chan says.

Another project with a message was Haiijaii, a piece made from recycled materials that she created in 2019 as part of a team for Wonderfruit, an arts, music and lifestyle festival in Thailand.

“It was designed to measure air quality – the faster the neon lights flickered the worse the air quality.”

She also started The Neon Girl, a project comprising six neon pieces created with six light masters from around the world, including Dutch neon artist Remy de Feyter.

“What I’ve discovered is that there are social and cultural factors that vary from country to country. This deeper look into the craft is what fascinates me.”