How a natural history museum showing human remains, including of a child and infant, is trying not to cross ethical red lines

- An exhibition displaying part of a collection of 50,000 human remains at Vienna’s Natural History Museum raised tricky ethical questions for its curators

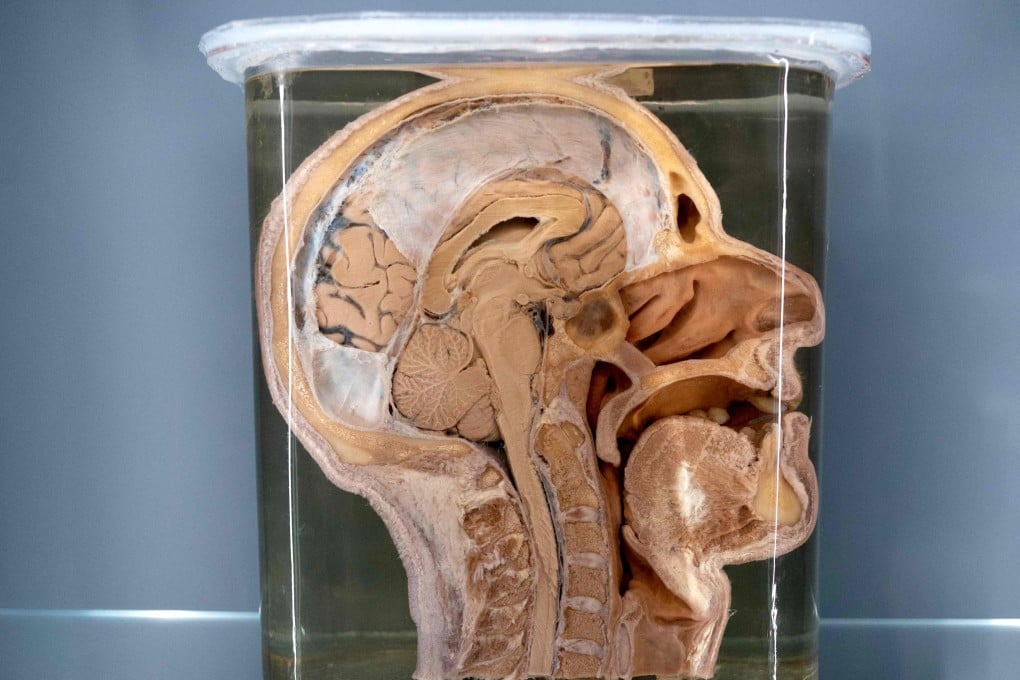

- Visitors can see human organs, skulls and body parts – exhibits that some other countries restrict to researchers

A vast, bloated liver. An infant with lacerated skin. The deformed skeleton of a young girl.

The recent renovation of one of the collections belonging to Vienna’s prestigious Natural History Museum provided curators with a new test of how to display its vast trove of human medical remains, some dating back more than two centuries, without crossing modern red lines of ethics and good taste.

The collection of around 50,000 human body parts was first conceived in 1796 to help train medical students.

In today’s world, such gruesome galleries raise tricky questions over whether the public good outweighs moral issues such as human dignity, power and exploitation, and the consent of those – admittedly long dead – subjects on display for all.

“We try to avoid voyeurism by giving as much explanation as possible,” said curator Eduard Winter, pointing out that photography inside the galleries is not allowed.

Winter said he hopes that when museum-goers are confronted with “a 30kg liver … they will realise what alcohol can do to the human body”.