Art project aims to change the conversation about tourist-trap village Sok Kwu Wan on Hong Kong’s Lamma Island

- Sok Kwu Wan is more than a strip of restaurants serving pricey imported seafood to tourists – that’s the message of Lamma Mia, a public art project

- 15 artists from elsewhere in Hong Kong have been invited to engage with villagers – whether native or incomers – and create art that speaks to the community

To most people in Hong Kong, Sok Kwu Wan at the southern end of Lamma Island is a place for tourists. They associate its inhabitants with a row of seafood restaurants serving rather pricey imports and with putting on excursions for day trippers to the Lamma Fisherfolk’s Village, a museum dedicated to keeping up an idyllic myth.

It is misconceptions like these that “Lamma Mia”, a three-month public art project, wants to challenge. By inviting artists who are not from Lamma to conduct lengthy interviews with islanders, organisers hope to draw out nuances and paradoxes of island living that can lead to broader questions about local identity, an idea highly pertinent in today’s world.

The community project for Sok Kwu Wan was initiated by Anthony Leung Bo-shan, an artist and cultural critic who has lived in that part of Lamma Island for more than 20 years.

Like many residents, she is an immigrant who is not from an indigenous Lamma family descended through the male line or from boat-dwellers who settled generations ago on the island. But this is “home” nonetheless, because a tight-knit sense of community within each village has been reinforced by the isolation that results from basic geography – the only way to traverse Hong Kong’s third-largest, blessedly car-free and extremely hilly island is on foot or by bicycle.

“There is an openness and cosmopolitanism here that is different from the land-bound villages in the New Territories,” Leung says.

She enlisted the support of the Art Promotion Office of the Hong Kong government’s Leisure and Cultural Services Department, which has been presenting a series of site-specific public art projects called “Hi!” since 2017, including in far-flung Chuen Lung Village in Tsuen Wan.

The project’s curators, who include Leung, Peggy Chan Pui Leng and Gum Cheng from the non-profit group Art Together, decided to ask 15 non-Lamma artists to deepen their understanding of the community and initiate long-term dialogue among residents.

That is why most of “Lamma Mia” is not about public art that is massive and eye-catching. There are pieces on view that grab the attention of passing hikers and local tour groups, such as Siu Wai-hang’s The Ray of Sight, the result of turning the so-called Kamikaze Cave (believed to be where a wartime Japanese suicide squad of explosive motorboats were hidden) into a camera obscura, and an engraving by Pauline Lam Yuk-lin that casts shadows onto a bridge overlooking the bay of Sok Kwu Wan.

Some of the quieter pieces have been placed inside a cluster of shipping containers in front of the village’s Tin Hau temple that have been converted to provide an information centre, small galleries and screening rooms for two films – one about the ferry that sails between Aberdeen on the south side of Hong Kong Island and Mo Tat and Sok Kwu Wan on Lamma all year round and other taking a close look at the cult of Tin Hau, the goddess of the sea that is a reminder of Hong Kong’s fishing heritage.

I’ve asked villagers to help me turn banana leaves into little pinwheels and attached them to a pagoda

An illustrated booklet contains a collection of oral histories told by 12 island residents.

That there are clearly defined categories of people in such a tiny micro-region as Sok Kwu Wan is representative of the us-and-them mentality that pervades any village, or island, culture.

There are “The Villagers”, meaning indigenous families; “The Water People” from a fishing background; “The Bay People”, meaning families who settled generations ago having come either from mainland China or elsewhere in Hong Kong; and “The Incomers”, first-generation arrivals not just from other parts of Hong Kong but from all over the world who have helped make the community truly diverse.

These identities can reinforce tribalism and stereotypes, and on top of that there is the erroneous assumption that Lamma represents a utopia of untouched nature, says Leung.

Pointing to the abandoned stone quarry that forms an unmissable backdrop to the bay, she says the island was in the past a major industrial centre. It is still a place that fuels much of Hong Kong’s economy today, since its most recognisable feature is the “three incense sticks”, or chimneys, of its power station.

Leung believes that to get different groups to talk to each other, the first step is to promote a sense of shared belonging and to better understand where everyone is coming from – their family background, their hobbies, what they like to grow (just about everyone on Lamma is a gardener to some extent).

Ho Yuen-leung, an artist and advocate of self-sufficient living, has set up a centre to demonstrate sustainable farming in the middle of Sok Kwu Wan and holds regular, free workshops. Two other artists from elsewhere in Hong Kong are struck by the island’s abundance of natural resources.

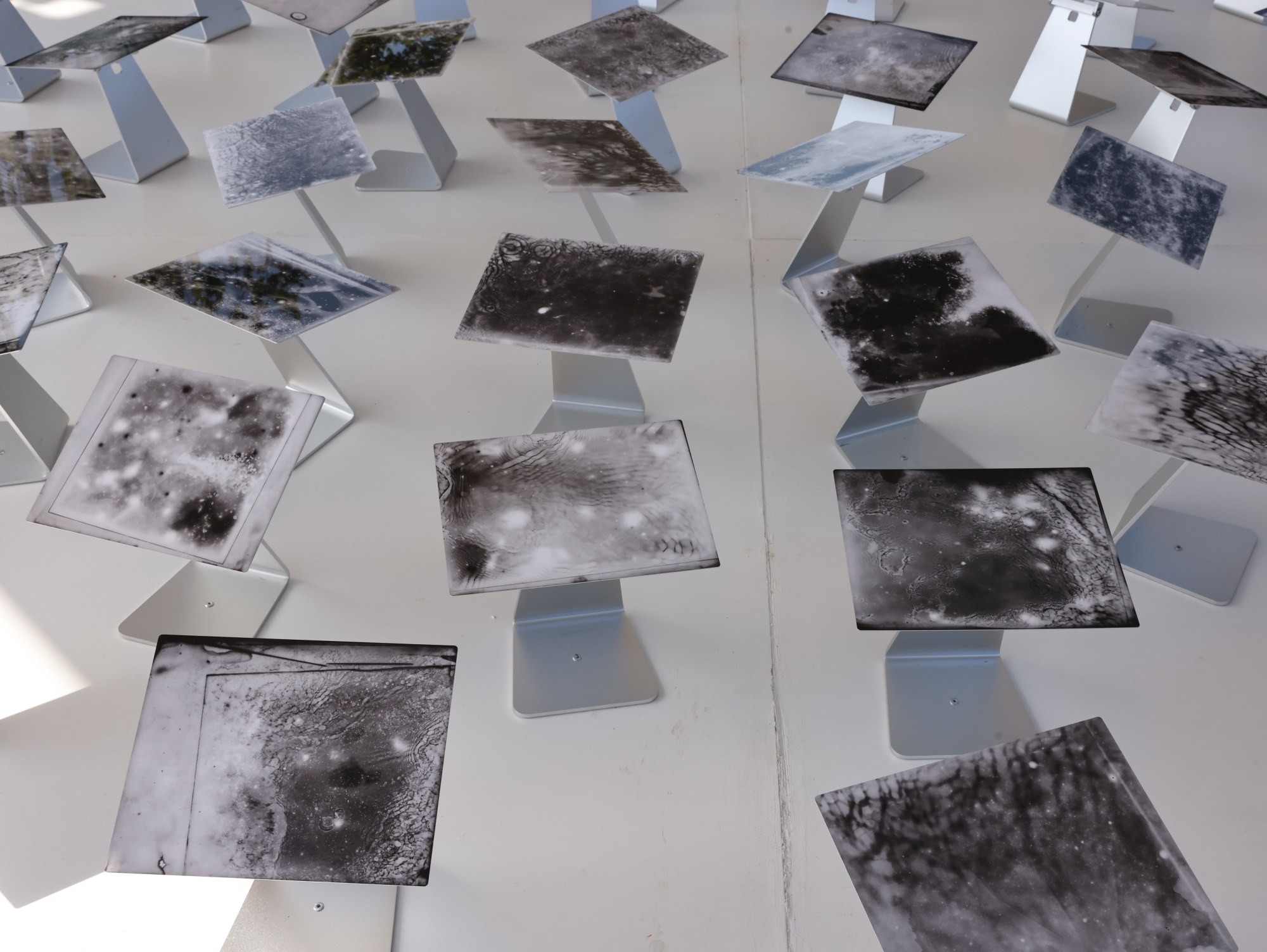

So Wing-po, whose art is informed by her family background in Chinese medicine, collected seaweeds and plant samples from the area and put them through a process called decellularisation that erased all living cells and proteins. Each sample comes with a story or a poem and they are shown collectively, bleached of all natural colours, in a cabinet installed next to the colourful and lively fish tanks of one of the restaurants.

Called Invisible Island, the work is a metaphor for the chance of renewal in Hong Kong after two years wracked by political turmoil and the coronavirus pandemic, the artist says.

Sharu B. Sikdar was drawn to the many banana trees in the area because they remind her of how ubiquitous they are in her mother’s hometown in the Philippines. “I always use nature to express myself. So on the island I felt a familiar connection. Here, I’ve asked villagers to help me turn banana leaves into little pinwheels and attached them to a pagoda next to the children’s playground,” she says.

Can art overcome tensions between old and new in Hong Kong’s North Point?

“Pinwheels are a universal symbol of childhood nostalgia, and I’d like people to come here and relax among them.”

Sikdar, born in Hong Kong to a Filipino mother and Indian father and a fluent Cantonese speaker, may seem to have a more fluid identity than the retirees who spend their days chatting at the restaurants. But Leung says that would be to forget how mobile islanders have always been.

“As the shipping line adverts hanging in some of the restaurants can attest, some of the villagers used to work on ships and they travelled around the world. Maybe it comes from living on an island in the middle of one of the world’s busiest shipping channels,” she says.

It may seem odd, if not downright territorial, for a major Lamma public art project to exclude the many accomplished artists living elsewhere on the island. (There are permanent art spaces in Yung Shue Wan, the main village, such as the Lamma Art Collective and the new Sinag Art Space.) But Leung says the hills that divide north and south Lamma have created two distinct communities, and Sok Kwu Wan is less familiar to people than Yung Shue Wan.

“We don’t have artists who live in Sok Kwu Wan, otherwise we would have invited them to participate. Also, we have chosen artists interested in community projects and who are eager to spend a lot of time with villagers. And ‘Lamma Mia’ is a Sok Kwu Wan project from which we want to project broader ideas about the importance of foregrounding local histories and culture,” she says.