Movies filmed in dying languages present untold stories, and an opportunity to inspire indigenous youth to learn their ancestral tongue

- Filmmakers are increasingly using indigenous languages in their work, from one spoken in part of Alaska to Mayan and Native American tongues

- Indigenous elders hope they will inspire the youth to learn the tongues; in addition, Hollywood films such as Moana have been translated into native languages

When Benjamin Young was asked to consult on a film to be made entirely in his ancestral Haida tongue, he thought the project sounded almost impossibly ambitious.

As head teacher and director of Haida Immersion Preschool in Hydaburg in the US state of Alaska, he knew the number of fluent Haida speakers could be counted on just two sets of hands.

“It was too crazy to be true,” says Young, whose indigenous people live mostly in Haida Gwaii, the tree-laden archipelago off British Columbia, Canada, that they have occupied for millennia.

“Make a full, feature-length film only in our language? I knew the complexity of the work it would take to pull something like this off,” he says.

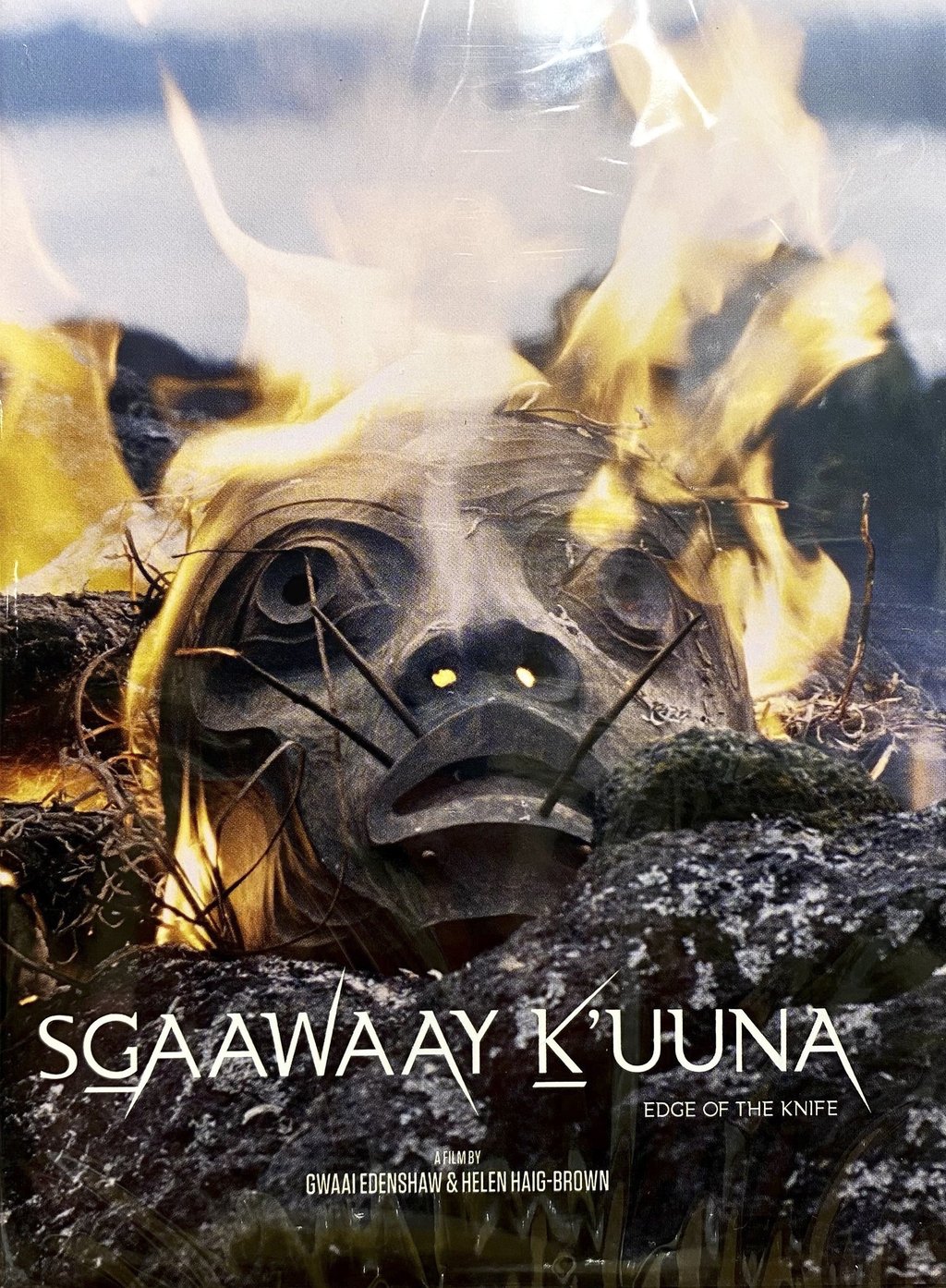

SGaawaay K’uuna, a largely indigenous effort inspired by the classic Haida tale of the wild man Gaagiixid, would ultimately be honoured by the Vancouver International Film Festival and Vancouver Film Critics Circle as the best Canadian film of 2018.

The movie, whose title means “Edge of the Knife”, also earned the critics’ nods for best director, best actor and best supporting actor in a Canadian film.