Levitation and levity in 2022 Venice Biennale’s Hong Kong pavilion, with Angela Su’s video art and hair embroideries

- Artist Angela Su mixes the story of a fictional woman who believes she can levitate with 1968 footage of anti-war protesters trying to ‘‘levitate the Pentagon’

- She is not making a statement about Hong Kong, she says, even if some viewers will want to see it that way

In her new film The Magnificent Levitation Act of Lauren O (2022), which is at the heart of Hong Kong’s exhibition at the 2022 Venice Biennale, curated by Freya Chou, she conflates fact and fiction in the story of a woman convinced that she had the power of levitation. In a dispassionate voice Su narrates real events in 1960s America using footage sourced from film and television archives while weaving in a storyline about an imaginary protagonist – the Lauren O of its title – and her fellow idealistic activists from a group called the Laden Raven.

Scenes of absurdity and hilarity (vaudeville performers, tightrope walkers, a woman travelling on top of a hot-air balloon) are intercut with clips from a “serious” documentary about the 1968 “levitate the Pentagon” protest against the Vietnam war, a Soviet “space dog” as it was being prepared for extraterrestrial flight, and a 1970s workshop in which a woman seemed to be howling while violent tremors went through her body. It was probably some intense exercise to release trauma, but her appearance was more suggestive of an exorcism.

“Arise”, which is the title of the Venice exhibition, is also a continuation of Su’s affinity with Gothic horror, which she expresses through intricate anatomical drawings and hair embroideries. A couple of older works here link the exhibition to previous explorations of transhumanism and artificial intelligence – big themes of our time that occupy many other contemporary artists exhibiting in Venice.

Yet it is tempting, for Hong Kong visitors especially, to see the exhibition as a thinly disguised comment on the political situation in Hong Kong.

There are certainly echoes of the 2019 anti-government protests as her 16-minute film asks whether the anti-war movement in the US should have escalated when peaceful demonstrations failed to yield results, and how a seemingly idealistic movement unravelled and resulted in many participants being arrested for violating national security.

Suhas been open about the fact that her work is informed by a desire for social justice. However, she insists that she is not making a statement about Hong Kong.

In a stirring opening speech, she explains that “Arise” is a response to a world that seems frozen, trapped in apathy or caught in conflict. While levitation (through the many images of aerial artists she uses) is a metaphor for resistance and personal liberation, it is levity, which shares the same Latin root word for “lightness”, that will help us emerge from a state of paralysis, fear and cynicism.

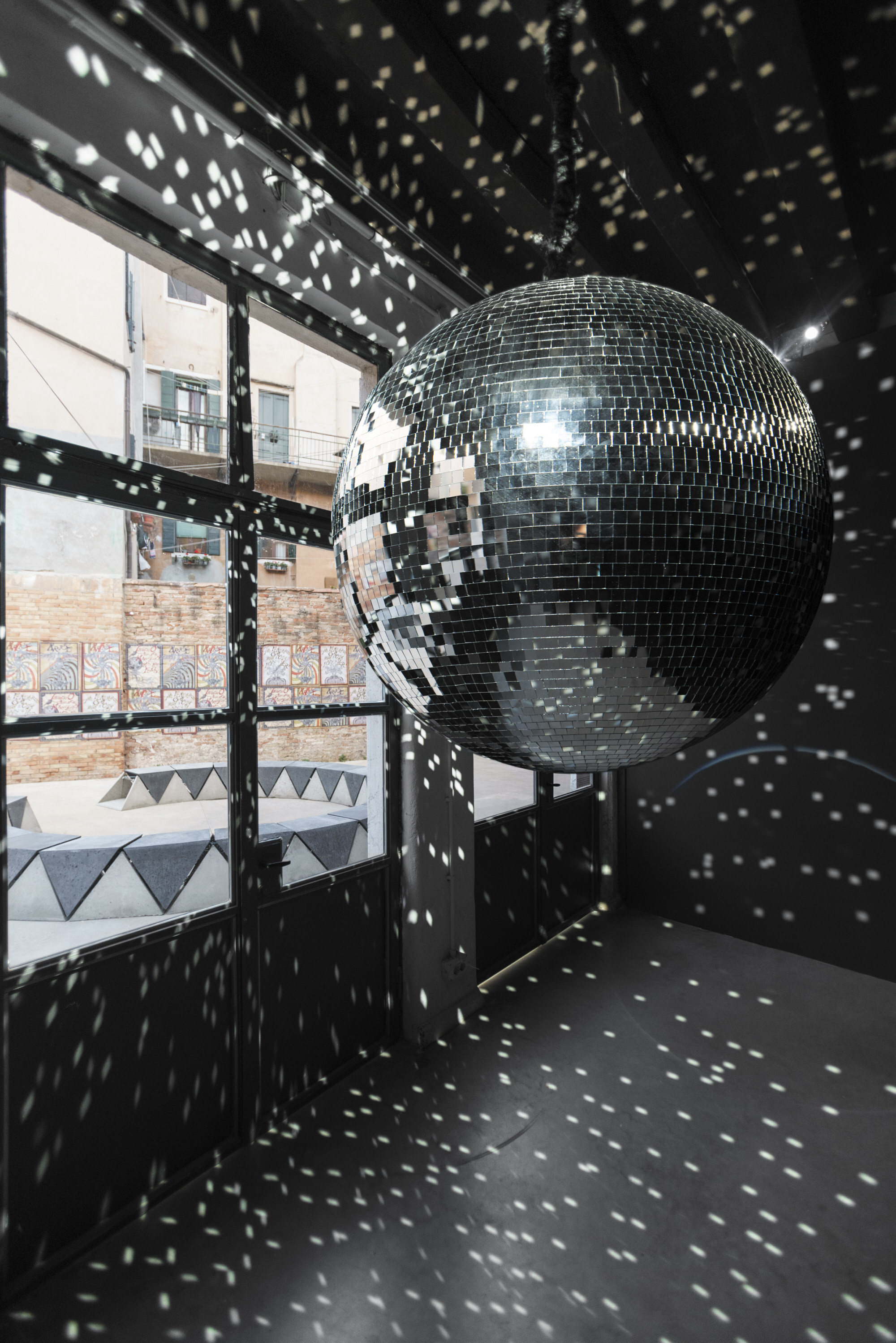

“‘Arise’ can interpreted as a reminder […] to see life’s heaviness and absurdity with a smile, with lightness, and with playfulness,” she says. Indeed, at the end of her film her levitating heroine metamorphoses into a disco ball, a sweetly neat ending.

Su appears on camera playing the role of one of the arrested activists. She is bound and suspended from the ceiling like in the rope torture Venetian authorities once administered in the Doge’s Palace, but shows no fear. Instead, she lies down in a padded sensory deprivation cell (the screening room where the video is playing is lined with the same noise-absorbing panels) and slowly pulls a miniature disco ball out of her mouth. It grows as it rotates and glitters.

At the room’s exit, an actual disco ball hangs as a reminder to keep dancing to whatever rhythm is thrown at us in these uncertain times.

The strength of “Arise” lies in its openness to different interpretations.

For example, there is a set of small hair embroideries that include an eyeball impaled by a sewing needle and a vagina and an anus stitched up. The gory images are confrontational and wince-inducing. One can see this as a protest against censorship – they recall the extreme acts of self-mutilation by Russian artist Pyotr Pavlensky. Equally, they may be a cruel satire of the state of being closed to the world.

Another video work, called Tack Tack Tack (2017), shows Su’s hands as she plays a version of the knife game: stabbing a pair of sharp scissors rapidly between her fingers until it draws blood. It is another symbol of where pain, fear and pleasure collide.

There is ambivalence, too, in the images of trapeze artists and tightrope walkers on screen and in the giant swing and black and grey circus ring installed in the Hong Kong pavilion’s courtyard.

There is no unalloyed sense of joy in these symbols of levity, which after all is a strategy for combatting the pain and deep sadness that have arisen from recent political and pandemic-related traumas.

Ultimately, the exhibition is a call to action. We do not know if our actions will land us in a padded cell, but being deprived of feelings would be the end of feeling human.

“Angela Su: Arise, Hong Kong in Venice”, Campo della Tana, Castello 2126, Venice, Italy, until November 27.