Profile | The creator of Hong Kong’s beloved rubbish monster Lap Sap Chung: artist and author Arthur Hacker

- Arthur Hacker, who worked for the Government Information Services, created Lap Sap Chung in the 1970s, the rubbish monster loved by Hong Kong children

- He was an avid artist, and released a number of books, and is currently being featured in an exhibition of his work

It was not the first publicity campaign organised by the Hong Kong government and it would not be the last, but it was certainly the most memorable.

His creator was an Englishman called Arthur Hacker, who arrived in Hong Kong in 1967 and died here in 2013, aged 81. Hacker liked to say that, being himself a red-haired foreign devil, Lap Sap Chung was a self-portrait.

For years, he worked in the Hong Kong Government Information Services Department, usually referred to as GIS. (The initials, so journalists used to claim, stood for God Is Speaking.) There he produced, in civil service anonymity, posters for many sober campaigns: anti-smoking, anti-drugs, anti-pollution. Some of these are now in the M+ Collection and can be seen in its exhibition “Hong Kong: Here and Beyond”.

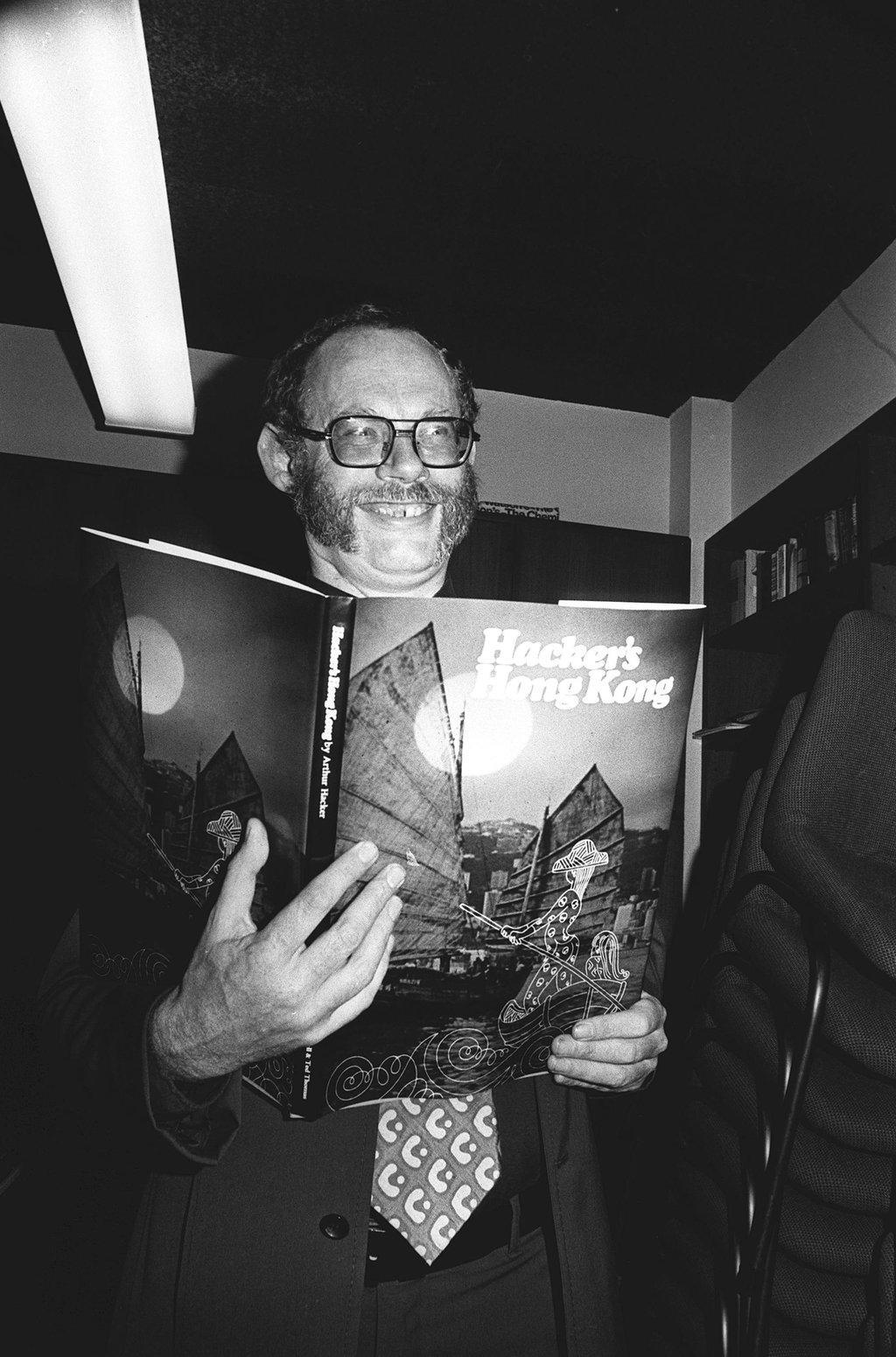

The off-duty work, however, was less restrained. Hacker’s office job was to tell Hong Kong’s citizens how they should behave, but in his own time he staked a visual claim by observing how they actually did. When his first book of drawings came out in 1976, with text by David Perkins, it was called Hacker’s Hong Kong. From a froth of flourishes and curlicues, an exuberant place and its people emerged.

His style was so distinctive – caricature, yes, but soft-edged – that, once you saw it, as the title promised, you started to view the streets through his eyes. Hong Kong was, Hacker explained, “a pop-art city” and he wanted to portray its “sweet side”. It’s true that some of the Wan Chai ladies (whom he called his “dahlings”) look more sour than sweet as they eye up hulking American sailors but you feel the artist’s affection.