‘It’s very much a Wild West’: how AI art generators are splitting the art world

- Advances in AI art generators are raising questions over copyrights, with many countries’ laws not explicitly covering AI-generated art

- The growing use of AI to produce magazine covers, posters or logos, for example, also throws up the question of whether AI will eventually replace artists

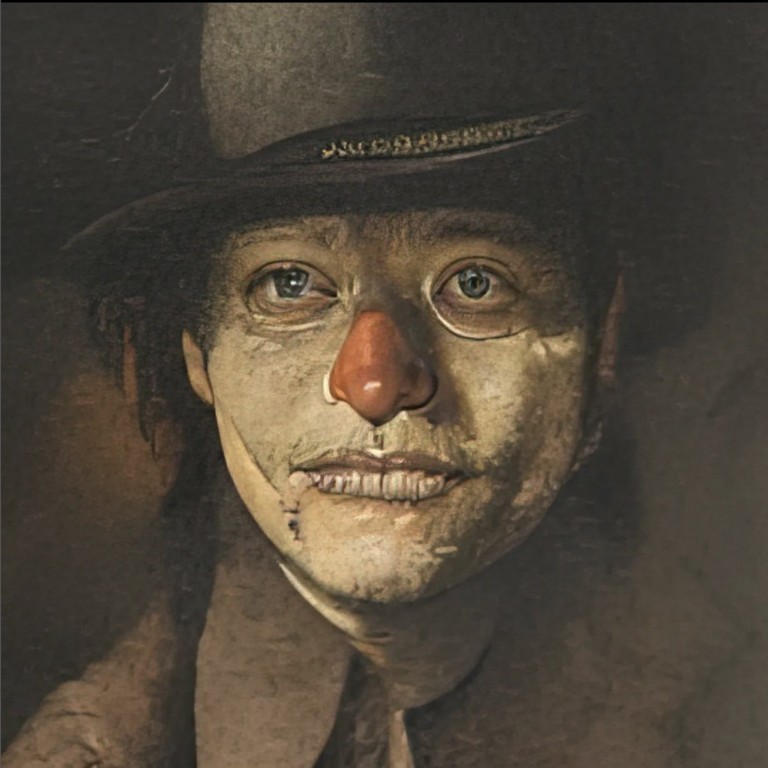

At first glance, the series of warped clown faces in a collision of primary colours appears to be the work of a painter – with typical hallmarks such as oily brushstrokes and smudged backgrounds.

Yet the images displayed by Scotland-based artist Perry Jonsson on his tablet were, in fact, created through artificial intelligence (AI) – reflecting a growing trend in the art world.

He used a machine learning programme, whereby algorithms take a text prompt and analyse data to produce thousands of images, before selecting and refining his favourite ones.

“They’re a bit creepy,” says the 31-year-old. “But what I loved was the humanity that shone through, and that’s what I was looking for – something that felt like an actual artist might paint.”

He adds that AI allows him to stretch himself creatively despite his lack of drawing ability.

A filmmaker by trade, Jonsson began dabbling in AI-generated artworks this year. He is one of a growing number of people in the creative sector experimenting with software that has sparked debate about the future of art and role of man versus machine.

What began in the 1970s as artists tinkering with the possibilities of computer programming has become a burgeoning business – with AI-generated pieces winning digital arts competitions and fetching huge sums at auction in recent years.

The most famous example, Edmond de Belamy (2018), a portrait depicting a blurry image of a man in a black shirt with a white collar, sold at auction for US$432,500 in 2018 – despite having carried a presale estimate of US$7,000 to US$10,000.

However, advances in AI have fuelled concerns over the ethical and legal implications of co-creating art with machines.

“It’s very much a Wild West,” Jonsson says, adding that he tries to “stay above board” when it comes to using copyrighted works. Yet he says it is difficult to know whether the data used by AI programmes to create his artwork is rights-free.

Some AI art-generation tools trawl images and mimic styles by using rights-protected works to create a new piece of art, raising fears among artists of digital theft.

Copyright laws in the United States and the European Union, for example, do not explicitly cover AI-generated art, leaving some artists to ask whether AI will help or hinder creativity.

The growing use of AI to produce magazine covers, posters or logos, for example, also throws up the thorny question of whether AI can – or will – eventually replace artists.

Award-winning 3D graphics artist and filmmaker David OReilly, who writes on the issue, warned that “everyone who contributes to AI accelerates their own automation”.

A 2020 World Economic Forum (WEF) study estimated that AI could destroy 85 million jobs by 2025, but also that the tech would create 97 million new ones in various industries.

From mechanical waiters and humanoid healthcare robots to digitally resurrecting dead celebrities, the growing use of AI has thrown up complex issues of ethics, copyrights and privacy.

Art is the latest sector to test the limits of law.

Stephen Thaler, the founder and chief executive of Imagination Engines, a technology company based in the US state of Missouri, had a copyright claim for a computer-generated artwork rejected by the US Copyright Office Review Board in February.

The board said his work, which depicts an empty railway track tunnelling through a wall of violet flowers, “lacks the human authorship necessary to support a copyright claim”.

Bernt Hugenholtz, a professor of copyright law at Amsterdam University in the Netherlands, says that future lawsuits will hinge on whether a person makes creative choices, which is a “very abstract test”.

If someone simply presses one or two buttons to produce art, or gives a general text prompt like “create a picture of a monkey wearing a silly hat”, that is not a creative act and the person could not be the author under EU copyright law, he says.

However, if someone uses a very specific prompt, generates many images, selects from those images, and carries out further edits, then it could justify authorship, he adds.