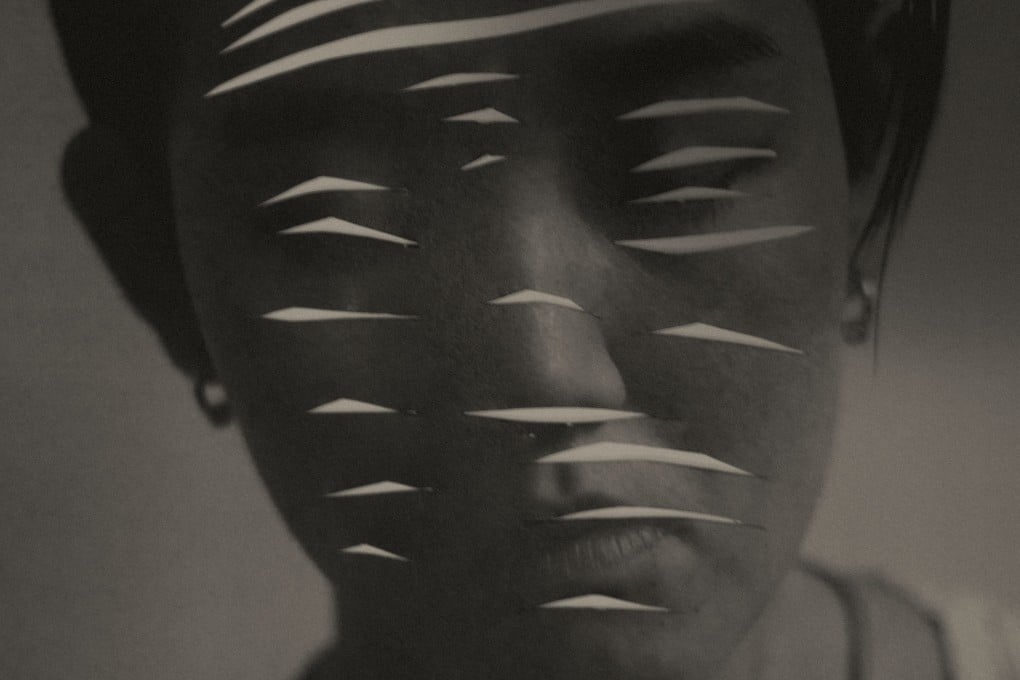

‘Psychic scars’: how non-binary Australian-Chinese artist Meng-Yu Yan’s works are often haunted by ghosts of the past

- Exploring both ancient and contemporary Chinese culture, Meng -Yu Yan’s works have been exhibited to acclaim around Australia over the past few months

- One of the artist’s latest series involves self-portraits incised with lines and shapes in an attempt to physically represent psychological scars

As a child growing up in Sydney, artist Meng-Yu Yan wanted to fit in. “I wanted to be your classic, white, beachy Aussie person with blonde hair and blue eyes,” says Yan, whose parents immigrated to Australia from China in the 1980s.

It was only on a university visit to Tianjin in northeast China that Yan, who identifies as non-binary and uses the pronouns they and them, fully embraced their heritage. A non-binary identity is one that is not solely male or female.

“My parents are very traditional and my idea of China had come from them, but on this trip in 2014 I met lots of inspiring young artists making really interesting work, people who were pushing boundaries. It showed me a different side to China,” Yan says.

Since then, Yan has made photographs, videos and installations that explore both ancient and contemporary Chinese culture.

“It’s a process of decolonising my own mind – trying to get access to ideas outside of Western philosophy, literature and art history,” says Yan. Much of Yan’s work also explores their own experience of being caught between East and West, and non-binary.