From June 4 to Occupy: 25 years of change in Hong Kong - in pictures

A book by veteran photographer and academic Tse Ming-chong traces the constantly changing face of the city over a quarter of a century

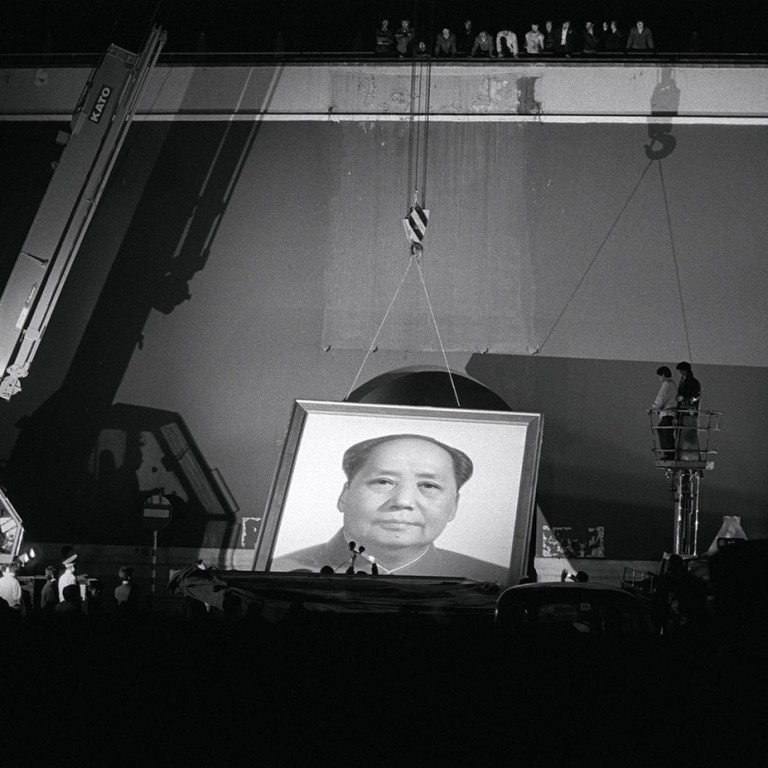

The opening and closing images in veteran photographer Tse Ming-chong's new hardback are like bookends that resonate across decades, but the interpretation is left to the viewer. The first picture captures the moment in 1989 when Mao Zedong's portrait was removed from Beijing's Tiananmen gate by workers after it was splattered in ink during the student-led protests. The book's final pages are devoted to photos taken in Hong Kong during last year's "umbrella movement" protests.

Tse, principal lecturer in the Hong Kong Design Institute's department of communication design and digital media, started poring over his vast catalogue with a view to compiling the book last summer, but says the project didn't feel complete until he snapped images of roads closed off by pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong.

"In a way, June 4 and the umbrella movement are very similar," he says. "I was stunned by the power of photography the moment I took the image at Tiananmen Square, which I chose to open the book with, and the images I took of the [sit-in] echo well," Tse says.

The umbrella movement photos will be exhibited in September at the Karin Weber Gallery in Central.

Societal change and progress, for better or worse, is one of the overriding themes of Tse's book, , published in May. The images in the 243-page book span a quarter of a century, from 1989 to 2014, divided into three periods, and are intended to express Tse's feelings for his home city. The captions and explanatory information are listed at the back because Tse wants viewers to focus on the images.

"If an image's meaning has to be stated with the help of a caption, I'd say that, in a way, the image fails to [communicate]," says Tse, who emphasises to his students that a photograph in itself is not what's important - it's what the photographer wants to express through it.

Many students think it's easy to create an image, he says, and don't understand the true nature of photography.

Tse feels that appreciation for photography is being lost in an age when cameras and mobile phones are ubiquitous. He describes the multitude of photos snapped by amateurs and posted on the internet as homogenous, like clones, taken by people seemingly devoid of independent thinking.

"The problem is that many people who take photos using their mobile phones don't care about the message an image is conveying. They only want to tell people what they've done. They want to prove their existence," Tse says.

In , the series of images that follow the Tiananmen Square photo, (1991), continue to illustrate Tse's classic documentary style. As you turn the pages, however, his approach becomes more experimental. Collections, including , , and the and , reflect how Hong Kong's physical and social landscape, and Tse's photography, have evolved.

"I constantly think about the nature of photography. It is nothing new, but it's not old either," he says. "My training is rooted in documentary photography, but I always think to myself, 'Does it end there?' For the past 20 years, I've been pondering this question and there's definitely a lot of room for exploration. I always try to let my contemplation shine through in my work."

The , for example, comprises pairs of photos that are opposite sides of footbridges, intended to be viewed in pairs. The viewer - standing between the images, as they were exhibited at the Cultural Centre - can feel the suffocation of being trapped in the concrete jungle.

Tse considers (1996-1997) as one of the most representative projects of his career. Inspired by former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping's famous reassurance that horse racing and dancing would continue in the city after the 1997 handover, the photos are of betting centres taken from various external angles.

"Gambling centres are very common; they exist in many neighbourhoods. They serve as a metaphor, like a temple or a church, in that they give people hope. If you can win, you might see a really big leap in your social status. It's a symbol of wealth," says Tse, who is considering a follow-up series, and a new one focusing on Deng's mention of dancing.

Tse insists that is not merely a photography book because it is more than just a retrospective of his work. It is a vehicle for his insights on the art of photography, its possibilities, and an interactive relationship with the audience. He put a great deal of thought into the design to achieve that, he says.

A detail of note is a flip-book feature. Flip the pages quickly and the small, square photos at the bottom corner or each left page appear to depict the passage of a day in the city. With the help of a computer, Tse took a photo every day over the course of a year - each one four minutes later than the last. Tse cites this as a prime example of the creativity possible in photographic art.

"People rant about photography being digitised, and get perplexed about the value of traditional methods," he says. "For me, the discussion doesn't stay at whether you choose to use film or not. It's not that simple. It's more about how photography as a medium can achieve something and be expressive when it's put in a digital context."

Besides its creative presentation, is a poignant documentation of the city's changing face over 25 years. Poring over his photos was an exhaustive experience, he says, not only because of the sheer volume, but because many were of places he had photographed growing up that had since vanished.

, from which the flip-book images are taken, was a 14-year project that charted ever-taller buildings eventually blocking the view of Victoria Harbour from Tse's Kwun Tong flat before he moved out. The series, meanwhile, captured some of the last old colonial structures.

"Hong Kong is a place without history because many landmarks and significant buildings have gone," Tse says. "It's something we need to think about. Of course, a place needs growth and development, but how should the decisions be made? I'm still very sceptical about the tendency to pull everything down and construct new buildings.

"It's like your own personal history, everything you've encountered, is being erased, so in the end you can only find it in old images. We may start to wonder if they ever really existed. Were they real? This is especially so for upcoming generations, as they have not seen them with their own eyes."

Hong Kong is a place without history because many landmarks and significant buildings have gone

Tse came up with the idea of publishing the book a year after he joined the Design Institute in 2011. The appointment gave him the chance to mull over his career and huge cache of photos as he searched for material during class preparation.

Tse initially trained at the Hong Kong Christian Service Kwun Tong Vocational Training Centre, and graduated from Baptist University's journalism department at the age of 40. He then went on to receive his master of arts degree in image and communication from Goldsmiths, University of London in 2004. He is also a co-founder of Lumenvisum, which is dedicated to advocating photography literacy.

"Hong Kong is very backwards in terms of visual training, as opposed to the UK and Europe. It's like a dark hole in our city, as our education system is very practical and subjects that don't require examinations are not encouraged," Tse says.

"That's why I started the workshop in 2007 with two friends. Back then, if you couldn't read you were considered illiterate. In this era, if you can't decipher images, you will be easily deceived."