Game review: The Beginner's Guide by Davey Wreden is very meta – and rather moving

With his follow-up to The Stanley Parable, Wreden has once again enlarged the medium

The Beginner's Guide, Everything Unlimited Ltd.

The nebulous and slippery relationship between a creator and his audience might not sound like the stuff of great gaming, but (for PC and Mac OS only), by Davey Wreden, is actually an extraordinary piece of work. To my knowledge, Wreden is the first major game designer to place himself, as a character, at the centre of a game that lures one into measuring the distance between it and its creator.

In late 2013, Wreden and his co-creator William Pugh became the toast of the video game industry after the commercial release of . Their work, which is funny and pensive, is one of the artistic peaks of the medium. It's one of those rare items, like or , that I recommend to people with little or no background in video games.

tells the story of an office worker who discovers that his colleagues have disappeared. Stanley, however, is never truly on his own since he is shadowed by a voice-over narrator who tries to interpret and guide his actions. The witty, affable narrator (majestically voiced by Kevan Brighting) tries to coax Stanley into performing a series of tasks. And like a righteously disgruntled office worker, it's up to the player to suss out all of the means of defiance. One's decisions lead to a small set of outcomes that shatter the illusion of free choice in spectacular ways.

In an internet post called Game of the Year, Wreden described the avalanche of attention he received for the game, "the emails from fans and journalists asking over and over and over where the idea for the game came from", as well as the "thousands of people asking you to carry some amount of weight for them, to hear them, to talk to them, to tell them that things are going to be OK, to not turn them away".

Knowing this makes Wreden's new game , all the more ironic for the way in which it depicts the relationship between an overeager "Davey Wreden" and a reclusive game designer, provocatively named Coda, the purported creator of the games inside of the game. At the start, the fictional Wreden (voiced by the actual Wreden) informs us that he'll be acting as our guide through Coda's games.

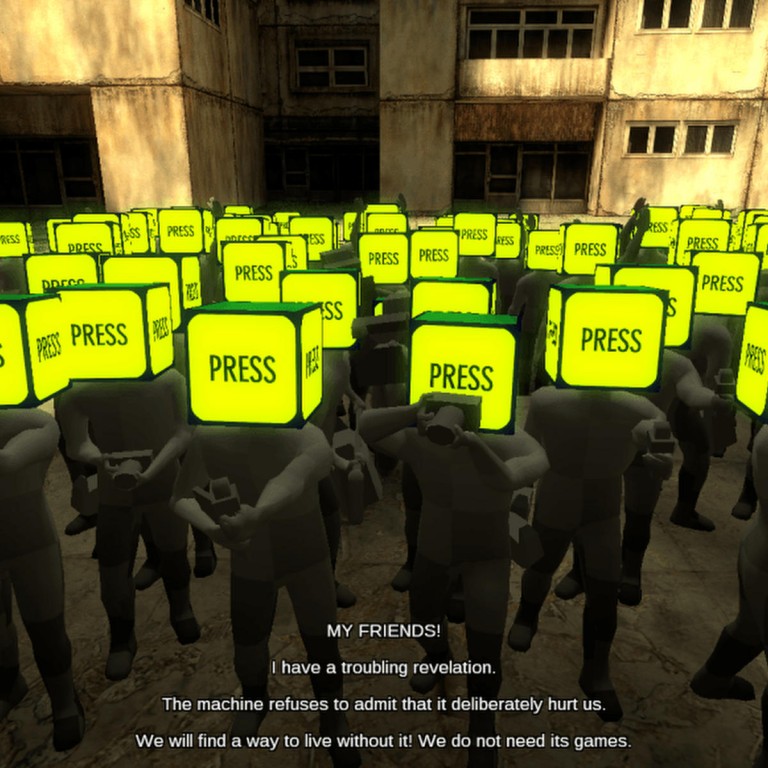

Beginning with an austere, desert-themed map, game-Wreden chats about the idiosyncrasies of Coda's first effort: a mod for , the ultra-competitive first-person shooter. Coda's user-created level contains neither firearms nor enemies. Aside from that, its most notable features are abstract cubes suspended in the air. Concentrating on this detail, game-Wreden remarks on Coda's habit of leaving quirks throughout his games to signal that it was made by an individual, not some mindless cog.

As the levels progress, they grow more conceptually rich. In the second chapter, the player is faced with a brick wall that reads "The past was behind her". To reach the exit of the short level, the player must walk backwards - an action that creates a visual metaphor for the clarity with which we perceive the past as opposed to our blind groping towards the future.

Over the stretch of , which takes about as long as a feature film to complete, it becomes evident that game-Wreden is not only presenting and interpreting the work but editing it as well. In the fourth chapter, the player comes upon a long staircase attached to a building, at the top of which a door is ajar. Part of the way up the staircase, one's progress is slowed to a crawl. Game-Wreden construes this as a symbol for the difficulty of trying to draw closer to Coda, and he offers a hotfix to return the player to a normal speed. I instinctively ignored his shortcut on my first go-around, though, preferring to experience the level as Coda intended.

The tension between Coda, who wants his work to speak for itself, and game-Wreden, who wants to share that work with the widest audience possible, echoes the codependent relationship between the narrator and Stanley. But in , I believe, the player's job is not to push against some external demand - what the narrator tells you to do - but to push against the interpretations made by game-Wreden and Coda.

We should be alert to the ways that game-Wreden colours our perceptions of Coda's work. But we should remain equally on guard against Coda's ideal, which finds expression through his games, that art should be received meekly and appreciated in silence. The truth is that without game-Wreden's interference, much of Coda's work would appear obtuse and unplayable. Game-Wreden spares us, for instance, from being locked in a prison cell for an hour as per the creator's original intent. All of this is further muddied by the fact that Coda - and his status as a creator - may in fact be wholly fictional, an added layer to the real Wreden's project.

If all of this sounds a bit heady, that's because is stocked with ideas worth contemplating. It's also one of the most emotionally alive games on the market. Its abstract game spaces would be much diminished without the flawed, vulnerable narrator desperately trying to rectify his mistakes. Where precisely the real Wreden stands in relation to his creation, I don't know, nor do I know the extent to which Coda is a wholly fictional character. But what I do know is that few game developers have ever ventured such an open-hearted project about human frailty - and knocked it out of orbit.

Tribune News Service