Art museums use apps in bid to attract younger crowds

There's a revolution under way in the world's museums and galleries and it's changing the way we learn about arts, science and nature

The museum of the future - one that uses technology to track down exactly where you are and maybe even which Jackson Pollock you'd like to look at - may not have quite arrived yet, but institutions around the world are quietly updating and innovating this kind of technology to engage with their audiences.

However, as Newton's third law states: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. So, for every app-loving, gadget-embracing museum curator or visitor there is a solitude-craving, analogue enthusiast who feels that pixelated screens and interactive devices interfere with the very soul of the museum-going experience. Their goal is to stand quietly in front of art and ponder its significance and place in history - without technological intrusion.

Regardless of the tension between the two philosophies, everyone agrees: museums are changing, perhaps at the fastest clip since the introduction of rudimentary audio guides in the 1950s. The institutions are updating themselves in hopes of staying relevant in a world where video killed the radio star - and where Snapchat killed the Facebook meme.

"Museums are not easy institutions. They have a reputation for being very closed, very formal, with too many rules," says Susana Smith Bautista, director of public engagement at the USC Pacific Asia Museum and author of .

"Technology is a bit more accessible and familiar. It's a fun way to get to your end goal, which is to help people appreciate and learn about the work."

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) recently launched a mobile app with audio tours, a searchable database of art on view, online collection information and push notifications alerting visitors when the bulbs on Chris Burden's landmark Urban Light sculpture turn on and how many solar panels sit above your head when you walk from one building to the next.

The new Broad in Los Angeles has a similarly enabled location-aware app that directs visitors to points of interest, which are elaborated upon by audio guides, including one for children that is narrated by LeVar Burton, one for architecture and one that features artists talking about their favourite works by other artists at the Broad - Sterling Ruby on Ed Ruscha's Heavy Industry, for example, or Jeff Koons on Roy Lichtenstein.

Digital touch tables in the special "Mummies" exhibition at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County allow guests to unwrap mummies virtually to discover more about the individuals' lives in ancient times.

The Getty Centre is in the vanguard globally of digitalising its collections and making them accessible to the public and scholars.

Locally, the Hong Kong Science Museum has been using digital interactive displays for some time, especially for international touring shows, to enhance understanding of exhibition content, though this practice has yet to be adopted by all government-run museums in the city.

In the US, the digital revolution is all the rage in large cultural institutions. Rich Cherry, deputy director of the Broad and co-chairman of the annual conference Museums and the Web says: "The thing that has changed from the mid-2000s is that everybody brings their own device now, which has really altered the museum business model.

"The primary space museums in LA are working in is in mobile apps. We live in a selfie culture. Everyone is on their phone. They're using them to engage whether we provide the app or not."

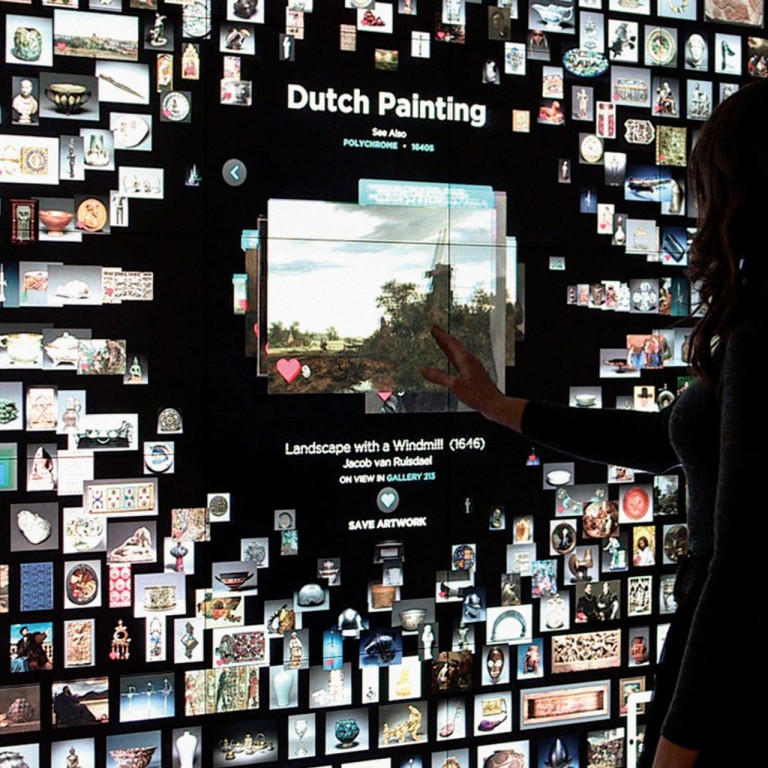

The Cleveland Museum of Art has a 12-metre touch screen Collection Wall that can display all art on view from the permanent collection - more than 4,200 works at any given time. The Tate Modern in London has Bloomberg Connects, where the interactive thrills include a 6.5-metre-long touch screen loaded with more than 35,000 works by 750 artists in its collection. Touch tables at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York allow users to access the collection and request information and images.

But because a key function of a museum is to encourage a personal experience with an object, some curators and visitors get annoyed seeing so many faces buried in screens and phones. Those responsible for visitor involvement are often conflicted about how and when to introduce technology into a gallery.

Rather than create expensive digital displays for their galleries, some museums are adding interactive art to their collections. It's handy when exciting new technology and the art are one and the same, not two separate pieces, Cherry says.

"What's been found over the years is that when you roll out a touch table or an interactive screen into a museum, there's never a great place to put it, because it competes with the visual art space," he says.

Helen Molesworth, chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art (Moca) in Los Angeles, agrees. "The experience of the viewer first and foremost should exist in real time in the museum, so I wouldn't necessarily want there to be a screen culture in the gallery, because it takes us immediately away from what we're doing," she says. "Museums are one of the places in culture where it really does look better on the wall than it does on the screen."

Molesworth says that a few years ago, she would have been gung-ho about introducing screens into the gallery, but that she had recently experienced a change of heart thanks to her own dependency on her phone.

Museums are one of the places in culture where it really does look better on the wall than it does on the screen

"We have a little vial of crack in our back pocket," she jokes, explaining that she isn't a fan of the mobile museum apps that are spreading in Los Angeles and elsewhere.

"The minute you pull out that screen, you say, 'Let me check my email. Oh, I got a text. Let me take a photo and put it on Instagram.'

"As a curator, I want to create time around the object. I think the screen takes the viewer into another time-space continuum."

For that reason, Moca is focusing on a robust website filled with detailed information about its collection, as well as special features such as discussions between artists about their work, rather than an app.

However, the technology debate has not stopped many museums from pushing further into the digital space.

"I think it's assumed that we want the galleries to be as quiet as a library, but that's not necessarily true," says Amy Heibel, vice-president of technology, web and digital media at LACMA.

"It's been proven over time that the use of technology in museums doesn't really detract from the experience of a work of art. It's optional, but a lot of people are already doing it - posting selfies and starting conversations on social media. It's what they're using, and we want to meet them there."

Karen Wise, vice-president of education and exhibits at the Natural History Museum, says her institution has asked visitors what they want, and the answer is clear. "They say more live people and more interactive experiences," she says.

Her museum's education-first mandate and abundance of school-age visitors have resulted in a heavy digital emphasis, including touch tables and an interactive multimedia gallery called Nature Lab.

"When you offer somebody the opportunity to touch a 65-million-year-old dinosaur bone, there's nothing like it, but to understand why things are there and how they were found, you have to allow people to go on a deeper journey," Wise says. "We have a game where visitors can dig for dinosaur bones themselves and imagine being a paleontologist."

Similarly, a touch screen at the Huntington gives visitors the virtual experience of firing their own 18th-century potpourri vase. You can pick a colour and stencil on a design. If you use too much heat, you're told that you've ruined your vase and that you have to start again.

"It's the public that drives how much information they want to access," says Catherine Hess, chief curator of European art at the Huntington. "There are grazers and then those who really want to drill down. We have presented the information in layers, so people can go as deep as they want to go."

The iPads positioned in strategic places in the historic rooms free up the architecture from what Hess calls "those nasty labels".

Those labels are, with unintended irony, called tombstones.

Tribune News Service